Every people must have, put forth and pursue a clear and compelling vision of what it wants for itself, of what it defines and seeks as a good society and world, and what place it wants to occupy in that world and in human history. In Kawaida, this is called a people’s collective vocation, a shared and compelling lifework and struggle to bring a special good in the world. Without such a collective vocation, there is no shared mission or meaning, no shared self- conception as a people or cultural compass to summon and direct a people’s intellectual, spiritual and practical energies and give them both a shared collective aspiration and anchor.

In the 60s, we shared a collective vision and vocation of freedom, justice, equality and power, i.e., political freedom, racial justice, social equality, and power over our destiny and daily lives. However, wracked by false assumptions of victory and reconsiderations within and violent suppression from without by the established order, the Black Freedom Movement began to dismantle and unravel. And many began to question and put aside the very shared consciousness of peoplehood and commitment to community and liberational struggle that brought us these victories, calling them no longer necessary, provocative and counterproductive.

At first simply, an unreliable rumor, it became an article of both willed fact and almost religious faith that America had been miraculously cured of its wicked racist ways and was now a saintly city on the hill we could all truly embrace. It is this refrain that gained new life with the election and presidency of Barack Obama, who, especially in his early years, regularly erased the harsh racist and class realities of history and current life from his speeches and spoke of a “more perfect union” which has in no way achieved perfection, and remains captive to corporate greed, world-wrecking and warmongering against the vulnerable of the world.

As much as we might want to distance our President from this, he linked himself to it. And as much as we might love him; see, rightly or wrongly, our destiny as a people tied to him; and need to defend him against the vicious racist attacks he endures daily; we cannot, in good faith, join him in the self-congratulatory songs he chose to sing in various versions of “America the Beautiful,” nor support him in actions at home or abroad which violate our sense of the good, the right and the rational. For there are ugly and oppressive things happening in America, indeed at home and abroad, and we are called upon by the history that has molded and made us and by an ancient African moral imperative to bear witness to truth and set the scales of justice in their proper place, especially among those who have no voice.

Whatever the specific elements of focus and emphasis in our collective vocation, it is and must always be morally and culturally grounded in both our best interests as a people and in the best interests of humanity and the world.

We cannot fight for humanity and exclude ourselves or fight for ourselves and exclude humanity. On the contrary, we must always craft a vision and vocation that represents, posits and pushes for the best of what it means to be African and human in the fullest sense of the word. Moreover, if we are to be who we have been as a people in this country and the world, a moral and social vanguard, then, we cannot deny our peoplehood or our unique history, culture and mission as an African people. Indeed, we have not only the right to exist as a people, but also the responsibility to do so, given the awesome legacy left to us by our ancestors.

For us, self-determination, Kujichagulia, is a moral imperative, a compelling ethical principle and practice. For it speaks to our natural right to be free, free from domination, deprivation and degradation and free to realize ourselves, i.e., to come into to the human fullness of ourselves in the context of our own community and culture.

It means, as we say of Kujichagulia in the Nguzo Saba, “to define ourselves, name ourselves, create for ourselves and speak for ourselves.” It clearly assumes and engages the possibility and need for alliance and coalition around shared temporary or ongoing interests. But the principle and practice of self-determination, reaffirms that we are responsible for our own life and liberation, and that no matter how sincere or numerous our allies, there is no substitute for the informed, organized and active self-determination of the people themselves. Moreover, only thru self-determination can we, as an African people and a moral and social vanguard, engage the critical issues and wage the vital struggles necessary to reconceive, repair and remake this country and the world and with other struggling and progressive peoples offer a new and needed way upward and forward in human history.

Liberals, leftists and deconstructionists alike, tend to call this insistence on cultural integrity and community autonomy “separatism” rather than self-determination. But rightly defined and understood, self- determination cannot honestly be confused or equated with separatism. Separatism is isolationism and resistance to exchange, but self-determination is the right and practice of freedom. In fact, the use of the category “separatism” to attack the right, claims and practice of self-determination denies the right of self-determination under the guise of saving the people from alleged irrational attachments to their community and culture and discourages the practice of self-determination by characterizing it as something negative and narrow.

Also, by conflating and confusing the self-determination of African people with “separatism,” liberals and leftists also reveal an individualistic bias. Their definition of freedom is essentially individualistic and has no place for the freedom of the people as a people, only individuals stripped of culture and community, standing culturally naked and in need for ideas and inspiration, identity, purpose, direction and kind deeds from others.

Ours is a great and ancient history and culture and we need not explain ourselves away, pretend to be freer than we are or praise the structures of our oppression in a vulgar sign of accommodation or submission. And like our foremother, Harriet Tub- man, we must, at this critical crossroads of history, redefine freedom from individual escape to the collective practice of self-determination in and thru community. Having realized our freedom is indivisible, we who feel we’ve “made it” must, like Tubman, turn around, face our oppressor and oppression and with victorious consciousness, dare to struggle to create a new and expanded space for lived freedom, social justice and human flourishing in the world.

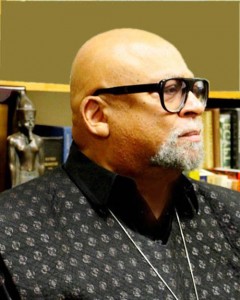

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.