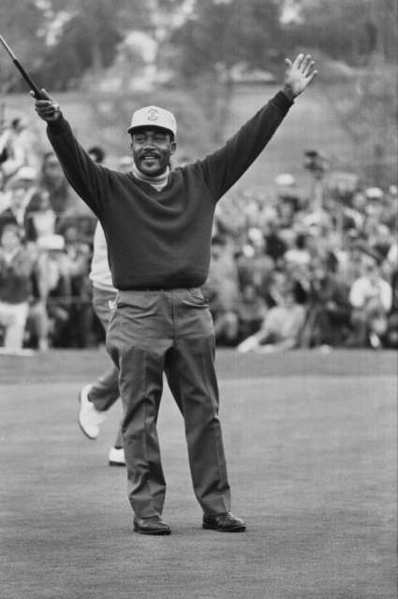

Charlie Sifford won the Los Angeles Open in 1969. After years of battling racial prejudice in golf, he was able to get the PGA Tour to drop its Caucasian-only clause in 1961. Photo by the Associated Press

Charlie Sifford overcame racial prejudice to help pave way for African-Americans to play on PGA Tour. He is just now beginning to receive honors for his struggle.

Sixty years ago, a black man could not set foot on this golf course. Today the Dr. Charles L. Sifford Golf Course is named for one who led the way.

On a bright June morning, Sifford sits at a table in the clubhouse grill, a cane leaning against his chair. “I just need this for balance,” he says. Like many legendary figures, Sifford is smaller than you might imagine, but his hands are large, his fingers as big as his cigars, and there’s a hint of the massive chest that helped him slam out tee shots on the PGA Tour not so long ago.

Bill Smith, the head professional, hurries to the table. “What would you like, Dr. Sifford?” Smith says. We offer to buy Sifford’s lunch but Smith says with a laugh, “Oh, Charlie knows he can have anything he wants here.” Sifford settles on a bottle of water.

A group of older black men approach the table to shake Sifford’s hand. “How ya’ doin’, Dr. Sifford,” one says. “Happy birthday, Dr. Sifford,” another says, removing his cap.

Sifford turned 89 the day before, June 2. “Yeah, I’m 47 now,” he says with a chuckle. The men laugh but they are shy too, and they stand back a bit, showing the same respect they would reserve for an aging war hero. These men know a lot about that battle.

Charlie Sifford traveled a hard road to golf glory, a road littered with land mines of prejudice, and now he is back in Charlotte, where he was born in 1922.

Sifford began playing golf the only way a black kid growing up in the 1930s could, as a caddie. Earning 60 cents a day, he gave 50 cents to his mother and kept 10 cents to buy cigars. By the age of 13, he could shoot par. Clayton Heafner, a fine white player who helped a number of young black men, taught Sifford golf technique.

“What did Heafner teach you that stayed with you?” we asked.

“All of it,” Sifford said.

At 17, Sifford was forced to flee Charlotte to live with relatives in Philadelphia.

“A drunk began calling me names and saying things about my mother,” he explained. “I picked up a Coca-Cola bottle and hit him upside the head. That’s when I left North Carolina. I took a freight [train] to Philly with another caddie, Walter Fergus. No plans. Just get out of town.”

Sifford would fight racial battles for the next 40 years.

Golf has long struggled with issues of equality, and when Sifford began playing professionally, in the 1950s, the PGA Tour had the “Caucasian-only clause.” From 1934 to 1961, the Caucasian-only clause was a part of The PGA of America’s by-laws that prevented non-whites from membership, and from competing on the PGA Tour. The clause was removed at the 1961 PGA Annual Meeting.

As he talks about his life, Sifford is at first cheerful. Then the hard questions come and he drops his head. He’s hesitant, his words are hard to hear, and he sinks lower in his chair.

Sifford remembers. He saw Bill Spiller and Ted Rhodes kept out of the game except for limited invitations. Unlike his compatriot Pete Brown, a sort of happy traveler who answered insults with a laugh, Sifford endured injustice grimly and fought his battles essentially alone.

His 1992 autobiography, “Just Let Me Play,” written with James Gullo, revealed the hurts. Gullo tells a well-researched story and the prejudice is a constant.

But Sifford’s book is less a rage than it is a slow burn. The stories are many, such as when, in the 1950s, five blacks were convicted of trespassing on a public course in Greensboro, N.C. When a court ruled that a public course had to be open to anyone, the city leased the course to a private company that instituted new rules barring blacks. The cities of Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Jacksonville, and Charleston, S.C., all used similar ploys to block blacks from public courses. And those golfers were just trying to play recreational games. Sifford was fighting for his right to work on the PGA Tour.

In 1957, Sifford won the Long Beach Open, not an official Tour event, but the field was stacked with touring pros. Still, he wasn’t allowed to compete in the Tour event the following week. Two years later he met Stanley Mosk, California attorney general, who helped open the door. Mosk knew that Sifford was barred from PGA tournaments in his state, so he presented Sifford as a California resident whose civil rights were being violated and asked the Tour to show reasons other than race why Sifford was denied membership.

The PGA had no choice and in 1960 made Sifford an approved tournament player, the first black to win the designation. Just a few months from turning 38, Sifford was officially a rookie on the PGA Tour. He didn’t have many good years left as a player.

In November 1961, the Caucasian clause finally fell. Three years later, Sifford was awarded full PGA membership. He was 42.

Threats, slights and insults continued, such as being prohibited from eating in dining rooms at many clubhouses. Friends such as fellow professionals Bob Rosburg, Jackie Burke Jr., Don January and Bob Goalby would go through the buffet in a clubhouse dining room, then bring their food into the locker room to eat with Charlie. Another friend, Major League Baseball’s ground-breaker, Jackie Robinson, warned Sifford what he was up against, saying people would call him names and perhaps even physically threaten him.

“Above all,” Robinson advised him, “you can’t be going after these people who call you names with a golf club. If you do that, you’ll ruin it for all of the black players to come.”

Sifford held his temper in check, but golf was rough going. After finishing fourth at Tucson, Sifford returned to California as the Tour headed South. While Sifford practiced and played for dollar bets at a public course, the NAACP began making noise about his plight. He was finally issued an invitation to the Greater Greensboro Open in North Carolina, his native state. He hadn’t been home for many years, but the thought that he might now be risking his life gnawed at him.

Not allowed to stay in a hotel, Sifford roomed at the dormitory of an all-black college, North Carolina A&T, in a room secured for him by a friend. Barred from restaurants, he usually ate at the homes of black friends. The college dorm was so noisy that Sifford accepted the offer of a black family to stay at their house.

Sifford opened the tournament with a round of 68. Late that night, he received a phone call at the private home. The owner handed Sifford the phone and a man on the other end unleashed a torrent of curses and racial epithets, warning him not to come to the course the next day.

Sifford was shaken. He considered withdrawing. He telephoned his wife, Rose, back in California. “Just keep moving,” she said. “They’re not going to hurt you on the golf course, but you make sure that you’ve got somebody with you when you go to your car.”

At the course the following morning, Sifford was nervous about the threats. After he teed off, a familiar voice yelled from the crowd of spectators, “Nice shot, Smokey!” Sifford recognized the voice as the one on the telephone. The taunting continued from the man and a gang of accomplices. They threatened, shouted and did everything they could to disrupt Sifford’s game. PGA official George Wash arrived at the third hole, and stayed beside Sifford. He urged the white trouble-makers to leave, but they stayed, shouting and cursing. Someone picked up his ball and threw it far from the fairway. Finally, police arrived on the 14th hole and took them away.

Not a man to back down, Sifford shot a 72 that day, and later called it one of the greatest rounds of his life.

This sad incident is related in Sifford’s 1992 book, “Just Let Me Play,” along with worse stories. Any one episode could have scarred Sifford for life but now, on this June day in 2011, his recollection of these sad events is vague. “Yes,” he says simply, or, “I don’t remember, it was so long ago.”

Over the past few years, some have tried to right the wrongs against Charlie Sifford. In 2004 he became the first black golfer admitted to the World Golf Hall of Fame, under the Lifetime Achievement category for his contributions to the game.

In 2006, the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, awarded him an honorary doctorate, which is where the “Dr. Charlie Sifford” comes from. Sifford, who likes the title, signs autographs that way.

On May 3, 2011, another honor was bestowed closer to home. Charlotte’s old Revolution Park Golf Course was renamed for the man who won five straight United Golfers Association National Negro Opens, the 1967 Greater Hartford Open, the 1969 Los Angeles Open and the 1975 Senior PGA Championship. It was a festive day at the newly-named Dr. Charles L. Sifford Golf Course, with some 300 friends there to honor him. The day was made more significant because the history of the course is so painful for so many.

John R. Rogers Jr., administrator of the Charlotte Historic District Commission, uncovered the truth about Revolution Park. The course opened in 1930 as Charlotte’s first municipal course, Rogers reported. There was one stipulation, however: if blacks played the course, ownership of the land would revert to the donor. No blacks were allowed.

On Dec. 16, 1951, African-American men showed up to play the course, beginning a long legal battle between the NAACP and the city. It ended five years later when the North Carolina Supreme Court ordered the City of Charlotte to either purchase the land or close the park.

Today this same course is named for a black man who wouldn’t have been allowed to play it for the first 29 years of his life.

Other fine black players, such as Jim Dent, Bobby Stroble and Walter Morgan acknowledge that it was Sifford, along with Lee Elder, who paved their way.

Morgan, a contemplative Vietnam War veteran who traveled with Sifford on the Champions Tour, knows how tough it was. When there was a roast for Sifford in California a few years ago, Morgan was there.

“Tiger Woods, who was about 15 years old then, was there and Charlie was trying to tell Tiger the things that he had to look forward to when he got out there,” Morgan said. “And he couldn’t tell him. He just broke down and started crying. He could not tell him. Yeah. He could not tell him.”

Years later, Morgan began reading Sifford’s book but, in despair, couldn’t finish. “The stuff that he had to go through… I couldn’t have gone through that, but thank God he did,” Morgan said. “His book is right, ‘Just Let Me Play.’ And he took it, that kind of stuff. I just don’t think I could have taken that. I really don’t.”

When Sifford was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame, Walter Morgan was in the front row.

“I was sitting right there,” he said. “I wouldn’t have missed it for nothing. That was really a proud day for all of us.”

In 2011, the USGA Museum initiated an oral history program for its African-American Golf Archive. A number of black golfers were interviewed for the project and, to a man, they were reluctant to speak of the bad times when racial prejudice ruled much of the game. Sifford, who endured so much, is the most reluctant of all. Over the years, he has softened somewhat, like a great boulder whose sharp edges have been smoothed by many sandstorms, but the old hurts lie just below the surface.

The oral history interview with Sifford concludes. His birthday gleam of good humor has faded with the intruding memories of bad times and he shakes hands somberly and slowly walks down the path, leaning a bit on his cane, “for balance.” He is an old man now. He has suffered. But there is dignity in Charlie Sifford’s slow stride and his chin – his strong, stubborn chin – is held high.

Check out the Sentinel Sports Section on Facebook and Twitter.

Sentinel Sports Section Facebook page:

http://www.facebook.com/?ref=logo#!/pages/Los-Angeles-Sentinel-Sports-Section/137328139648009

Sentinel Sports Twitter page: