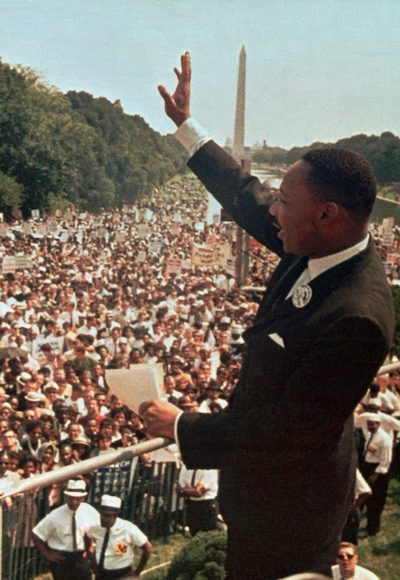

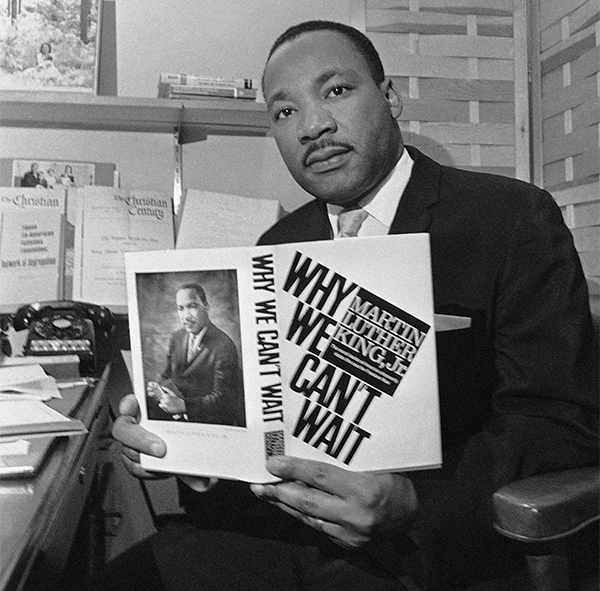

Advancements in social justice require several ingredients — and African-Americans are certainly familiar with the basics by virtue of our history: faith, leadership, moral courage. Certainly Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. embodied all of these. But he also understood the importance and value of narrative, and the art of framing issues for Americans of all stripes to appreciate and engage in the civil rights movement.

When Dr. King declared that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”, he was invoking the moral high ground of an inclusive framework for the civil rights movement in America. While the civil rights movement was principally about the plight of African-Americans, he connected our justice struggle to that of any oppressed group, anywhere across our nation and globe. The door swung wide open for partnership and inclusion in the struggle. It was about us, but it was also bigger and more than about us.

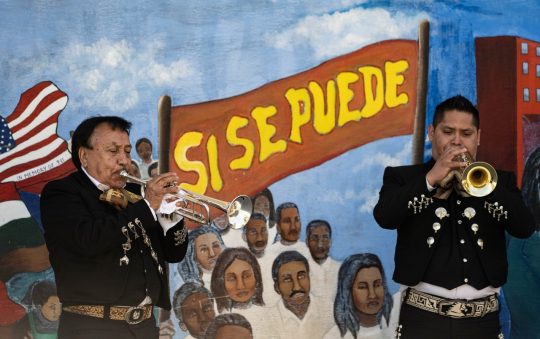

Narratives and frames can be deployed for negative and ill effects as well. The politics of exclusion and demagoguery that emerged from our nation’s recent Presidential election is a painful reminder of this phenomenon. Anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim rhetoric promoted a narrative of “exclusion” rather than “inclusion”, and has emboldened hate, white nationalist and supremacy groups in recent months – hate crimes and hate incidents are back on the rise.

I became smitten with the work of community health back in the mid-to-late 1980’s, as a practicing pediatrician in communities in Camden and North Philadelphia. My wake-up call was the emergence of a truly evil and pervasive innovation: crack cocaine. Cocaine is a highly euphoric and addictive drug, but prior to the 1980’s was generally too expensive for residents in low income communities to purchase – one needed at least $100 in cash flow to purchase the powdered form. When “Crack” burst upon the scene in 1984, suddenly folks with limited incomes and poor cash flow could purchase cocaine – Crack could be found and purchased on street corners for as little as five bucks. This highly addictive drug provided 20 minutes of well-being and euphoria for oppressed, depressed, marginalized, and struggling individuals — people lacking hope. It proved that the absence of hope, in fact, could be lethal.

The Crack cocaine epidemic was utterly devastating in its speed and in its reach. It swept across urban America, leaving wreckage and chaos in black families and communities in its wake. Rates of property crimes, sexually transmitted diseases, child abuse, premature births (known as “crack babies”), domestic violence, gun violence and gang violence all exploded.

As if the effects of crack cocaine weren’t bad enough, our nation’s response was nearly as harmful, and certainly more enduring. The crack epidemic led to a new criminal justice and public safety narrative called “Three Strikes and You’re Out.” It was a punishment and incarceration narrative, that quickly evolved from bumper-sticker to all manner of federal, state, and local policy changes in sentencing for drug-related crime use. Well-chronicled in Michelle Alexander’s terrific book, The New Jim Crow, the legacy of racism was joined at the hip with the criminal justice system – all under the guise of effective Public Safety.

As a practicing pediatrician serving inner-city low income families at the height of the crack epidemic, I was equal parts mortified and outraged. The nation’s response to the medical-health epidemic of crack addiction was to criminalize it. Instead of a substantial increase in access to community mental health and drug treatment services, our nation built jails. Dollars for prison construction climbed upwards in public budgets, as community organizations providing prevention services and youth supports pinched pennies. They still do – ask any executive director of a youth-serving organization in Watts or Inglewood.

The punishment narrative spilled over into our nation’s public education system, as “Zero Tolerance” policies in schools exploded, following in the glide path set by Three Strikes and You’re Out. Black and brown boys, in particular, experienced a more than 300% increase in school suspensions at the very same time that our nation’s prison population increased by more than 400%. Message to our young men and women of color in our schools: we don’t want you here if you act out.

Police departments and the LAPD now find themselves in a peculiar and uncomfortable position, with a crisis of legitimacy found in many urban communities across the nation. The narrative and punitive policies of Three Strikes and You’re Out and a voracious school-to-prison pipeline leaves police departments perceived by many in our community as part of the problem. Add in the occasional tragic police shooting of unarmed African-American males, and we have the necessary ingredients of deep and profound civic and community distrust.

The matter of police shootings has now taken center stage in the discourse of race in America. Yes, it is absolutely clear that organizations like Black Lives Matters and others have every right to be outraged and aggrieved in asserting rights, justice, and accountability with police departments. But I offer two points of caution in hyper-focusing on police shootings as the prize for civil rights in Los Angeles, and the nation. The first is that even if we were to achieve the lofty objective of eliminating every police shooting of African-American males across the nation, this falls short of the real prize for justice: if we succeed in eliminating police shootings, but fail to improve graduation and employment rates in young black males, we still fall well short of meaningful justice and prosperity for our young people.

Secondly, we heap substantial outrage on police chiefs and police departments for failing young African-Americans at the flashpoint of a controversial police shooting – but at the very same time, express only tepid levels of disappointment when the systemic prevention and youth development supports our kids need and deserve go unattended – something is out of balance with our priorities. Abysmally, seventy-five percent of black boys in the third grade across the nation are not reading at grade level proficiency; black boys are being criminalized and suspended out of school at extraordinary rates; community-based mental health services and after-school programs seem to be a luxury rather than a standard of practice at the community level; state and local budgets heavily emphasize jails and prisons over gang prevention and youth development programs. Our outrage about these issues must match or exceed that which emerges after police shootings. Let’s work to prevent the conditions that lead to police shootings in the first place.

Finally, what does this mean for the struggle for social justice in Los Angeles? It means the following:

- Los Angeles cannot look to either Washington DC or the nation for the path to social justice. The rest of the nation is simply a decade or two behind where we are in LA. The Trump election resurrected echoes of law and order, Rodney King-era politics, anti-immigrant Prop 187, anti-minorities Prop 209, and the “Three Strikes” culture of hyperincarceration. Los Angeles and most of California is beyond the narrative of exclusion; we are moving in the right direction.

- Los Angeles must assert leadership as the epicenter for a new narrative of inclusion, prosperity, wellness and prevention supports for all. LA needs this, California needs this, and our nation needs this.

- L.A. has come a very long way from the Darryl Gates/old LAPD, Rodney King, OJ Simpson trial era of civic discourse regarding law enforcement. Build on this path of progress. When civil rights warriors like Connie Rice, Pastor Chip Murray, and John Mack now work in concert with the LAPD in service of accountability and trust, that is a journey and path we must build upon.

- At the same time, we need the push from Black Lives Matter and similar younger activists to push all of us to move faster and harder on matters of accountability and transparency.

- The old narrative of Public Safety and Criminal Justice is prime and ready for a new narrative. LA must lead the way in this regard for the nation. It means focusing on grade level literacy for black and brown boys; it means ending the practice of early criminalization through avoidable school suspensions and expulsions in our young people; it means an after-school activity supported for all of our children; it means having more mental health and counseling supports for children coping with stress and trauma; it means reducing public spending on prisons and jails and increasing funding for prevention and youth support programs. Let’s swap Public Safety for something known as Community Safety.

As we recall the contributions of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, our nation struggles with a paired set of narratives that stand in the way of progress for African-American communities specifically, and social justice generally. The first is the President-elect Trump-embraced narrative of exclusion. The second is the enduring narrative and policy environment of punishment and incarceration. Spurred on by the memory of Dr. King, we in Los Angeles must endeavor to provide our nation with a re-energized narrative of justice, inclusion – and prevention.