(GIN) – South Africans marked the 40th year since the death of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko with a wreath-laying ceremony at the Kgosi Mampuru Correctional Centre.

An African nationalist and African socialist , Biko was at the forefront of a grassroots campaign known as the Black Consciousness Movement during the late 1960s and 1970s. His ideas were articulated in a series of articles published under the pseudonym Frank Talk and later, in two books.

Nelson Mandela called him “the spark that lit a veld fire across South Africa”, adding that the race-based Nationalist government “had to kill him to prolong the life of apartheid”. In an anthology of his work in 2008, Manning Marable and Peniel Joseph wrote that his death had “created a vivid symbol of black resistance” to apartheid that “continues to inspire new black activists” over a decade after the transition to majority rule.

Johann de Wet, a professor of communication studies, described him as “one of South Africa’s most gifted political strategists and communicators”.

“Steve Biko fought white supremacy and was equally disturbed by what he saw as an inferiority complex amongst black people,” said President Jacob Zuma at one of the memorial events recalling Biko’s life. “He advocated black pride and black self-reliance, believing that black people should be their own liberators and lead organizations fighting for freedom. He practiced what he preached with regards to self-reliance and led the establishment of several community projects which were aimed at improving the lives of the people.”

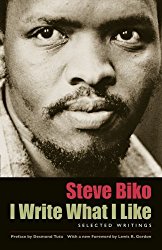

“They may have killed the man, but his ideas live on,” wrote Professor Tinyiko Maluleke of the University of South Africa in an editorial citing Biko’s writings: “I Write What I Like” and “Black Souls in White Skins”.

Although Biko’s ideas have not received the same attention as Frantz Fanon’s, the men shared a highly similar pedigree in their interests in the philosophical psychology of consciousness, their desire for a decolonizing of the mind, the liberation of Africa and in the politics of nationalism and socialism for the ‘wretched of the earth’, according to Professors Pal Ahluwalia and Abebe Zegeye of the University of Adelaide and South Africa.

Biko died on Sept. 12, 1977 from injuries sustained while in police custody at what was then called the Pretoria Central Prison. His murderers, four officers of the security branch in Port Elizabeth, were denied amnesty by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in February 1999.