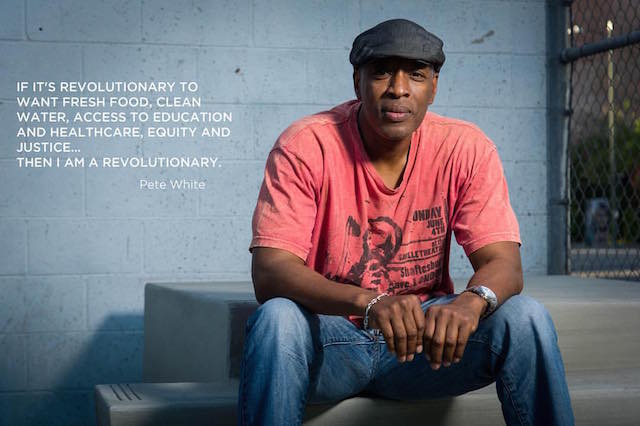

Longtime homeless activist Pete White, LA Community Action Network executive director and founder, goes one on one with the Sentinel about housing, feeding, and empowering L.A.’s homeless

Pete White, executive director and founder of the Los Angeles Community Action Network (LA CAN), has advocated for the poor and homeless since 1999. White spoke with Sentinel contributor Sister Charlene Muhammad about LA CAN’s origin, the politics of homelessness in L.A. County, and housing, feeding and empowering residents on Skid Row, the nation’s largest homeless population.

Sister Charlene Muhammad (CM): How did LA CAN come about?

Pete White (PW): LA CAN actually came about as a result of me looking for my cousin, Herman, on Skid Row. Herman, like so many other Black brothers and sisters, was struggling with sobriety, and he traveled to Los Angeles from Texas, and he called my mother – and this is early 1990 – and said Auntie, can I come to Los Angeles to get clean and sober.

If Herman couldn’t stay clean and sober in Texas or Louisiana, there was no way he was going to stay sober in Los Angeles, with the amount crack cocaine out in the streets, White told his mother. Nonetheless, she welcomed him. Herman remained that way for about a week and a half before his addiction kicked in, White said. Herman landed in Skid Row, according to White.

PW: Back in the day, we would go downtown and shop … but I didn’t know that Skid Row existed, and someone called me and told me I saw your cousin Herman on 5th and Crockett. … I did not find my cousin, but that day, I really found myself, because I looked all around, and there was nothing but Black bodies everywhere! Black bodies in the shadows of what I consider the skyline of oppression, because Skid Row is situated right under the towers or in the towers of Arco Plaza, and and all these multinational corporations. Then when you look to the North, you see City Hall, and you see the court building, and so, within a stone’s throw of all of these centers of power laid Black bodies, laying out on the street and no one cared. No one cared enough to think about building power to move the system. And, it was for me, and this didn’t happen that day of course, I had the epiphany. The thought happened, when I saw who could arguably be my mama, my sister, my auntie, my uncle, my dad, all of that moved me to say this is family. But, it would be a bit of time before I was able to do my sort of assessment and my sort of landscape on what existed in Skid Row and what did not exist in Skid Row, our way of building power.

White said he thought and still believes Skid Row, particularly for Black organizing, is one of the premier destinations to build power. When he says Skid Row, he’s not just talking about L.A. Skid Row, but skid rows or poverty rows anywhere, he said. In those places White said are found the intersection of all the issues and policies and White Supremacy seated in one place.

PW: Coming to Skid Row, you’re going to understand the 1994 Omnibus Crime Act Bill that Bill Clinton passed. You’re going to understand welfare reform in Skid Row. You’re going to understand the industrialization in Skid Row. You’re going to understand the 2006, 7 and 8 foreclosure crisis in Skid Row and how and who it impacts. You’re going to understand the lack of affordable housing at low and extremely low levels of affordability in Skid Row. You’re going to understand that, in general, but in particular, you’re going to understand how that impacts Black people, so at the beginning of the day and at the end of the day, I’ve always been concerned and interested at how to empower, mobilize, build power amongst Black people. As an organization, it’s really funny. We’ve been unapologetically Black from the get go, and because we sort of focus on the work on the ethos of the Black radical tradition, even when we have non-Black people, allies, accomplices and other members, they also understand that we’re moving and moved by the Black experience, because if Black folks aren’t picked up, lifted up, no one else will be.

LA CAN is training residents across L.A. in urban gardening, with an eye and effort around gardening to produce fresh herbs and other crops to sell to local businesses, White said. This year, the organization is looking at branding and marketing. In addition, it canvassed communities in support of Measure H, which voters passed to allow a 0.25 percent county sales tax for 10 years in order to fund homeless services and prevention to the tune of about $350 million.

CM: Can you elaborate on part of LA CAN’s 2017 food program?

PW: In 2017, a lot of people don’t even know about LA CAN’s food program and our micro-enterprise. For the first year, we moved 10 tons of organic fruits and vegetables. People don’t know in Downtown Los Angeles, most of the produce that enters the West Coast comes through Skid Row, but folk in Skid Row can’t get their fresh fruits and vegetables. In South Central, where we’re at as well, we actually work in Jordan Downs and in the Pueblos, also communities that are starved, that are supermarket-starved, so we started pop-up markets in various communities where we teamed up with local farmers, and we buy fresh, organic produce from them pennies on the dollar. And we take the savings, and we take these fresh fruits and vegetables to communities to make sure our families have access to fresh fruit and vegetables.

CM: Thank you.

(This feature interview was completed with support from New America Media.)