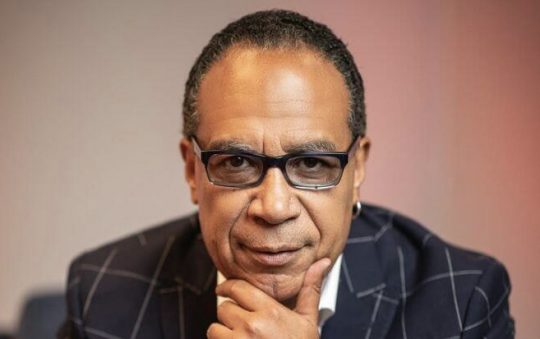

Vintage Sammy Davis Jr.

Cool Sammy Davis Jr.

Sammy and Altovise

SAMMY DAVIS, JR.

“He acted on stage and screen; he was a singer, dancer, author, comedian, impressionist and musician: Mr. Bojangles”

He was called the world’s greatest entertainer. Sammy Davis Jr. lived life to the fullest and though small in stature, he did everything big. His physical being was the total opposite of his lifestyle–small in size but big in accomplishments. He inherited his showmanship traits from his parents; his father and his mother were part of the vaudeville act, entertaining and tap dancing respectively, and that was the world that greeted Samuel George “Sammy” Davis Jr. in 1925 in Harlem, New York. By age three, young Sammy started performing and his father would often take him on tour.

His parents split up when he was still an infant and his father maintained custody of young Sammy. As a result, he ended up being raised by his paternal grandmother. He learned dancing from his father and his uncle, Will Mastin who together with Davis Sr. and young Sammy later on became the Will Mastin trio.

When he was about six years old, young Sammy made his movie debut with Ethel Waters in “Rufus Jones for President” followed by a brief appearance in “Season’s Greetings.” During the 1930s, the trio continued to play vaudeville cabarets. To get around strict child labor laws, he was often billed as “Silent Sammy,” “the Dancing Midget” while he walked around backstage with a rubber cigar in his mouth and a woman on each arm.

In 1943, Davis entered the U.S. Army, where he learned how much Mastin and his father had been shielding him from the hate and prejudice that were rampant in society–in the entertainment industry and the U.S. Army too. Of the experience, Davis said, “I could see the protection I’s gotten all my life from my father and Will.”

While in the service, he was part of an integrated entertainment unit and used his “special” skills to entertain the fighting men and maintain a healthy morale for the war effort. For him, his talent was his most potent weapon; and he used it throughout his time in the army. After two years, Davis was discharged and rejoined the trio. Soon after, they broke into the big-time club circuit followed by a successful Hollywood engagement.

In November 1954 while returning to Los Angeles from Las Vegas, Davis was involved in an automobile accident that almost killed him. He lost the use of his left eye and was forced to wear an eye patch for more than six months after. However, that was a minor inconvenience for Davis as he continued working often times with Mastin and his father. He was eventually fitted with a glass eye, which he would wear for the rest of his life, and his career was moving forward by leaps-and-bounds.

While recuperating from the accident, Davis was introduced to the history and the culture of the Jewish people and related it to his experiences as a Black man. And though he was born to a Catholic mother and a Protestant father, he converted to Judaism. He was reportedly intrigued by one particular passage from his readings about the Jewish people’s unwavering spirit of resignation that had given them a will to live which no disaster could crush.

As his solo career was moving ahead, Davis scored a hit on his first Broadway show, “Mr. Wonderful” in 1956. This was followed by a string of recorded hits: “Hey There,” “Mr. Wonderful,” adopted from the Broadway show and “Too Close for Comfort.” His first big starring role came in 1959 in “Anna Lucasta” opposite Eartha Kitt. The same year, he did “Porgy and Bess” alongside some of Hollywood’s finest Black talent including Sidney Poitier, Dorothy Dandridge, Diahann Carroll, Brock Peters, and Pearl Bailey. The film won an Oscar and a Golden Globe award.

But with all of his success as a showman and an entertainer, Davis was first and foremost a Black man in America, and that carried its own set of social mores, taboo, written and unwritten laws, codes of conduct and the price of acceptability and rejection. It was well known that Davis accumulated his vast arsenal of showmanship skills and versatility, and that he worked tirelessly out of a sense of loyalty and an urge to please his audiences, friends, acquaintances and mentors–most of whom were White. But the prevailing social realities did not allow that sense of loyalty to be returned. In addition, though his mother was of Cuban ancestry, Davis would claim that she was Puerto Rican because Cuba’s communist leanings were just beginning to surface in a negative way in America’s media.

It also appeared that Davis lived recklessly. He became involved in an interracial relationship with Kim Novak, one of Columbia Studios valuable commodities to the extent that his life was threatened. It was even rumored that there was a contract out on him and that he might be in line to be kidnapped. Miscegenation was taboo–on and off the screen–in Hollywood and at that time; it was still illegal in 31 states. As the situation began to produce unbearable, negative effects, Davis hurriedly married Loray White, a Black woman, a show girl. The marriage too, was a ‘show’ marriage which lasted just a few months. Some reports say it was annulled, others say they were divorced. Either way, Ms. White was reportedly paid $10,000.00 for her time and (in)convenience. Her most famous role was as a Nubian woman in “The Ten Commandments.”

Throughout his engagements in Las Vegas, Davis would always include Mastin and his father as a part of his routine. In 1959, he became a member of the Rat Pack, a group of like-minded cronies who, like Davis, enjoyed the fast life. The group consisted of Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Joey Bishop and Peter Lawford. Two women were said to be a part of the group: Shirley MacLaine and Angie Dickinson. A slogan attributed to them was that they never let business get in the way of having fun.

Davis made three movies with the group; his first one was their biggest: “Ocean’s Eleven” (1960) which became a cult favorite. Filmed in Las Vegas, the group was “play” all night and film during the day; they went days non-stop. That’s when rumors of the use of alcohol and drugs began to surface, especially with Davis, who was supposed to be an adherent of Judaism which made such excesses against his religious teachings. He made two other movies with the group: “Sergeants 3” (1962), a remake of 1939’s Gunga Din and “Robin and the Seven Hoods” (1964).

Once again the prevailing social mores were injected into Davis’ life even as a member of the Rat Pack. He would be a headliner in Las Vegas casinos and hotels, giving top-of-the-line performances but was not permitted to reside at the hotels where he was performing or gamble in the casinos, eat at the restaurants or drink at the bars. (Using the hotel pools was out of the question. It was reported that one of the Las Vegas hotels drained its pool rather than let Dandridge use it). Davis was not the only Black entertainer experiencing these indignities; others included Nat King Cole, Count Basie, Dandridge, Johnny Mathis and of course, Mastin and his father. Not was this the norm in Las Vegas, it was society’s norm. It was happening across the country in places like Miami, Los Angeles, and New York.

In 1960, his marriage to a White Swedish actress, May Britt, stirred up a hornet’s nest–he was attacked from all sides. Blacks thought he was a sellout and Whites thought he overstepped his boundaries. As a member of the Rat Pack, he was caught up in the political atmosphere which was entwined within the Civil Rights Movement. There were the Kennedys and Sinatra on one side, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Black community on another side, and Davis somewhere in-between with a White wife, a relationship that made everyone uneasy–his friends and his detractors. He was not invited to the Kennedy inaugural party though it was hosted by Sinatra who obviously thought more about the president’s position than about his fellow Rat Pack member.

Even though his personal and family lives were on shaky ground, his career did not suffer. In 1964, he was back on Broadway starring in a musical “Golden Boy” for which he was nominated for a Tony Award. As in “Porgy and Bess,” it attracted an array of future Hollywood big names including Lola Falana, Louis Gossett, Jr., Johnny Brown, Roy Glenn and Ben Vereen. But the brighter his entertainment star shined, the dimmer his family relationship became. Davis began to realize his hectic schedule was cheating him of his family and vice versa.

However, there was a pot of gold at the end of his rainbow. As his status as a heavyweight in the entertainment industry grew bigger, he was able to make solid demands in venues that practiced racial discrimination and in so doing the new generation of Black performers were spared much of the indignities he and others had undergone. Much of those successes were attributable to him along with the civil rights pioneers during the 60s.

There was a new crop of entertainers on the scene and in order to reconnect with their younger audience, Davis tried Berry Gordy’s Motown label for awhile but it did not last. He wrote his autobiography, “Yes I Can” and had a hit single at the end of the 60s, “I’ve Gotta Be Me.” His marriage to the Swedish blonde ended in 1968 because of an alleged affair with he had with Falana.

Then about the same time, he had an unexpected smash hit with the “Candy Man.” It scored big and put him right back on top. In 1970, Davis married Altovise Gore, whom he had met while doing “Golden Boy;” Rev. Jesse Jackson officiated the nuptials. They stayed married for the rest of his life. But in 1972, he stirred up another hornet’s nest. This time it was because of a White man, President Richard Nixon. At a youth rally, he was photographed hugging the president in a show of support. He lost friends and fans. Many Black folks have negative thoughts about Republicans and having just came through the turbulent 60s, the idea of a successful Black entertainer publicly supporting a Republican was unthinkable, to put it mildly. After the Nixon administration, he returned to the Democratic Party.

Just after Davis had joined the Rat Pack, he had signed up with Sinatra’s label, Reprise Records where he stayed throughout the 60s with few minor deviations. He was reluctant to do the “Candy Man” which turned out to be his biggest hit. During the rest of the 70s and the 80s, Davis did a lot of variety shows and guest spots on television including “All in the Family,” “Charlie’s Angels” and the “Cosby Show.” He also performed the theme song for television’s “Baretta,” made a few movies and continued his live act in Las Vegas. Davis made some television commercials in Japan and did some of the same when he returned to America. He penned a memoir to follow his autobiography in the early 80s titled “Why Me?”

He was honored in a variety of ways throughout his career including a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame; a Kennedy Center Honors; the NAACP Spingarn Award; the NAACP Image Award; an Emmy Award for the Sammy Davis, Jr. 60th anniversary celebration; and an induction in the International Civil Rights Walk of Fame, posthumously.

An avid photographer, Davis enjoyed shooting family and acquaintances, and was also an enthusiastic gun owner, who often participated in fast-draw competition. He was always articulate and well spoken though he did not have much formal education.

Because he worked and played so much and so hard, Davis missed a lot of quality time with his children: Jeff, Mark, Manny and Tracey who co-wrote a book about her famous father, “Sammy Davis, Jr.: My Father.”

Davis died in 1990 from throat cancer which resulted from being a chain smoker; he smoked four packs of cigarettes a day most of his life. In death, the Mastin Trio came together again; he was laid to rest in Forest Lawn Cemetery, Glendale, next to Mastin and his father. He preceded his mother, Elvera Sanchez (95 years) and his grandmother, Luisa (112) in death.

Davis was portrayed by Don Cheadle in “The Rat Pack,” a movie about the group.