Jimmie Herron, Jr. came into the Los Angeles Sentinel offices with a special request. The Los Angeles native is on a mission and the Sentinel plays an integral part in his agenda. You see, Herron shares a special history with the Sentinel, some good, some bad, but he wants to add one more piece to the puzzle.

He was born in Shreveport, Louisiana in 1947 but his family moved to Los Angeles in 1957.

“We lived in a small, back house on 29th and Vermont. I attended Vermont Ave Elementary School,” said Herron.

“Now, when I look back at my elementary school year books, you can see the White flights of people moving out of the inner city to the valleys.”

Herron remembers playing with White and Mexican kids in the community back in the day, his memories serving as snapshots of a different time.

“We made our toy scooters out of old roller skates, 2x4s and wood, milk crates,” said Herron.

He remembers watching popular TV shows of the time like “Leave it to Beaver,” “Father Knows Best,” and “My Three Sons.”

Related Stories:

“You get the picture. There were no Crips and Bloods, drive-by shootings weren’t in our vocabulary, no mass school shootings on the nightly news, no video games with exploding heads-and blown-up bodies, just to say, a more innocent time for children,” said Herron.

Herron describes a situation that no child should ever have to endure. At the age of 12-years-old, he witnessed his father getting shot over a crap dice game.

“Needless to say, how traumatizing it was to see my bloody father, not knowing if he was going to live or die, affected me,” said Herron. “That incident was what I call a ding moment in our family’s life.”

He continued, “He lost his job, we got evicted out of our house, he fell deeper into alcoholism, started abusing my mother with violent outbreaks that caused my mother to eventually divorce him.”

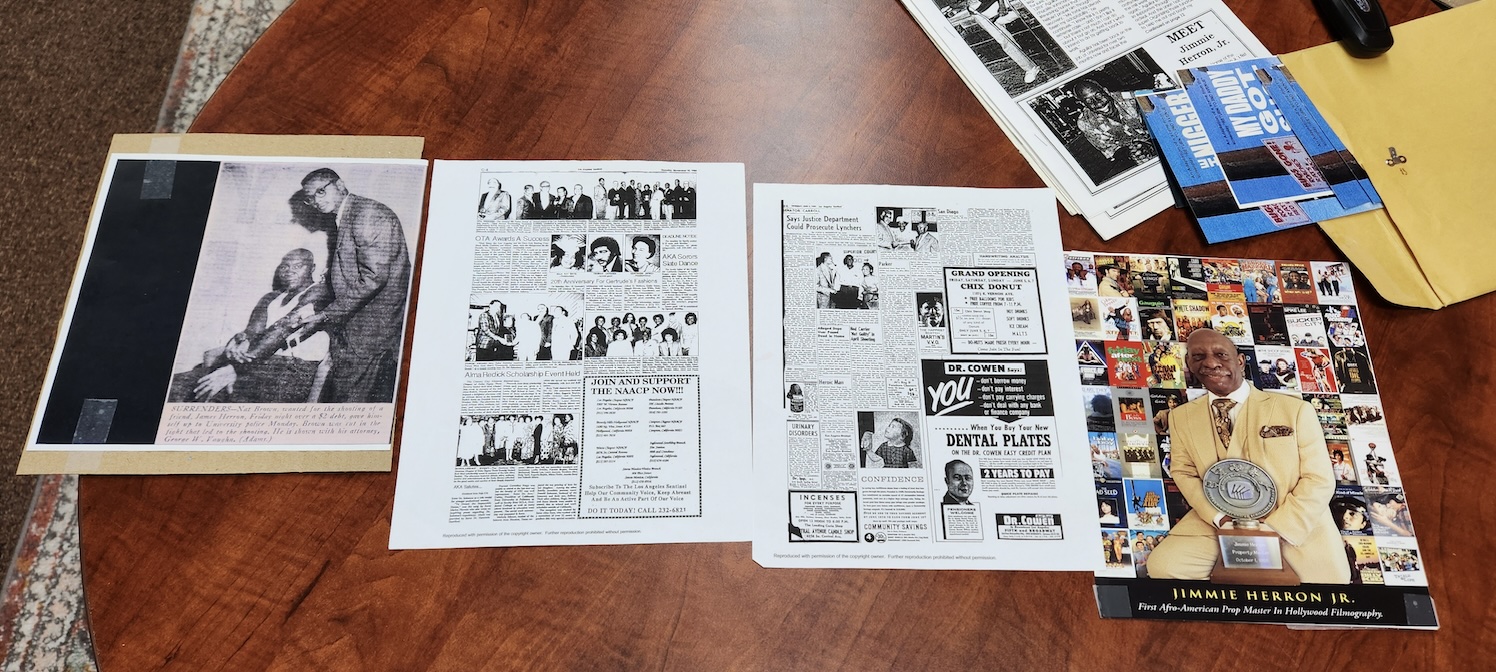

Herron recounted that the situation was made even worse when the incident was reported in the Sentinel. Even though the man who shot his father turned himself in to police, the story was out there in the public eye.

“You will never know how that made me feel,” said Herron.

“How embarrassing knowing friends and neighbors would see it, knowing when I went to school, I would get bullied and teased by the kids, ‘Your drunken daddy got shot over $2 dollars.’”

Although a dark moment in his life, Herron shared it was also a pivotal turning point. This is when he decided that his life was going to mean something to him and his family. He wanted to make something of his life that would make his mother proud.

“Through a minority program in 1969, which was very controversial, I walked through picket lines of White disgruntled workers,” said Herron. “I got a job at Universal Studios in the prop department.”

Herron continued, “After years of avoiding all of the pitfalls so many Black men fell into – being late for work, drinking on the job, flirting with White women – after years of perseverance, I got my Prop Masters Card.”

Props are hats, guns, a wine glass, a bomb, etc. that you see in film and television. A prop master works with production designers, set decorators, and art directors to work out what props are needed on set. Prop masters also recruit carpenters, artists and prop makers as well as manage the schedule for production.

Herron has worked on the sets of films such as “Harlem Nights,” “The Wood,” “Baby Boy,” and “Love & Basketball,” and television shows like “The Dukes of Hazard,” “Kenan Kel,” and “The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr.” just to name a very, small few.

“I worked on a few films, back in the ‘80s that pretty much encapsulated all the A-list Black actors in the industry,” said Herron. “I’ve worked, practically, with every Black actor than won an Academy Award.”

When asked what he liked most about being a prop master, Herron said he liked “having an input in the project.

“Having a visual input that people could see and just the opportunity to learn from so many different people.”

Herron has received the outstanding achievement award, from the Los Angeles Black Media Coalition, for being the first Black prop master in Hollywood’s local #44 in 1988. The picture from the event, he stated, was in the Sentinel.

“As a 12-year-old kid, to say my name and picture would get in that paper, how could that even be possible, but after all the years of seeing my mother praying on her knees for her family, I know it was divine intervention,” said Herron.

Herron has accomplished much in his life and has laid a foundation for others pursuing a career as a prop master. All that being said, he hasn’t forgotten his main reason for coming to the Sentinel. He hasn’t forgotten something special he wants to present to someone special.

“My mother is 95-years-old in her last days in a nursing home,” said Herron. “She will not be with me as long as she’s been with me, so I would like very much to get an article in your paper of me and my son Dervon for being the first father and son prop master team in Hollywood.”

His request was met by the Sentinel as his amazing story, a piece of Los Angeles history —Black History – would make it in the paper. He showed up to the Sentinel ready to have his picture taken, but he left a wealth of information. Herron is also proud that his son carrying on in the same career.

“It feels pretty good,” said Herron about seeing his son follow in his footsteps. “He survived, he’s successful, he has a decent career, so I’m proud of him.

“It makes me proud that we both accomplished things in this world. I’ve gone to memorial services, funerals and I’ve always said, when I leave here, hopefully, somebody got something good to say about me,” he said.

“There’s going to be a whole lot of guys that come along after me that maybe did big shows and worked on this, worked on that, but they never had to walk through a picket line to get to work.”