When a figure as awe-inspiring and change-driving as the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. leaves our midst, the resulting devastation is profound. In efforts to articulate the deep sense of loss that was felt, many have described the moment in history as though a close family member had passed away.

Dr. King was shot and murdered on April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, but across and even beyond America, no Black person—nor person of any other color for that matter—was untouched.

However, a number of Black writers at that time were taking to their typewriters as they mourned and coped, and mapped out their own blueprint for a better nation through their art.

As Dr. King’s final speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” explored themes of unity, peace, and progress, so did the works of these 10 authors, each of them published in 1968.

Alice Walker – “Once”

Renowned novelist Alice Walker’s first volume of poetry, “Once,” centered on her experiences traveling to Africa and participating in the Civil Rights Movement — as she was very much inspired by Dr. King. In this collection, she also composes meditations on love, one of King’s signature messages, choosing a spare Japanese haiku form throughout.

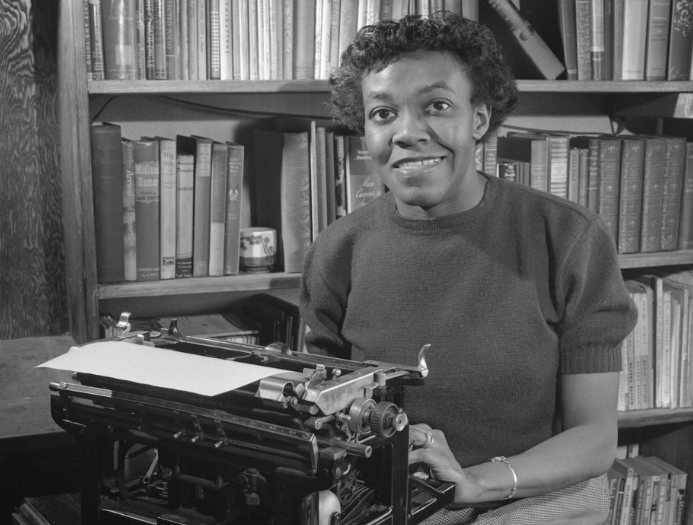

Gwendolyn Brooks – “In the Mecca”

Long revered and decorated, Brooks published “In the Mecca” in 1968, which consists of a long narrative poem about inhabitants of a vast, decrepit apartment building on the South Side of Chicago, which arguably serves as a metaphor for urban life and a country in discord. She also wrote a direct tribute for Dr. King entitled, “Martin Luther King, Jr.,” which was included in “I Am the Darker Brother: An Anthology of Modern Poems by Negro Americans,” published the same year.

Related Links:

https://lasentinel.net/how-teachers-honor-martin-luther-king-jr-s-legacy-in-2022.html

Sonia Sanchez – “The Bronx is Next”

Award-winning author Sonia Sanchez, who later wrote the poem “Morning Song and Evening Walk” in honor of Dr. King, contemplated cycles of destruction and how to break them in her first play, “The Bronx is Next.” Written in 1968, it depicts a revolution in the slums that finds Black people setting their own tenements on fire.

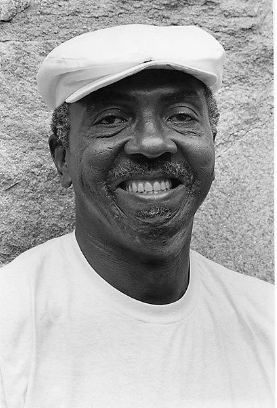

Etheridge Knight – “Poems From Prison”

Convicted of robbery in 1960 then subsequently serving eight years in the Indiana State Prison, Knight’s transformative story was extraordinary as he emerged as a widely celebrated poet, earning both Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award nominations. With a poem entitled, “Peace,” even though the exact publication date in 1968 is unknown, the work is uncannily thematically aligned with King’s ethos and one of Knight’s poems deals openly with the mourning of Malcolm X’s death not three years prior.

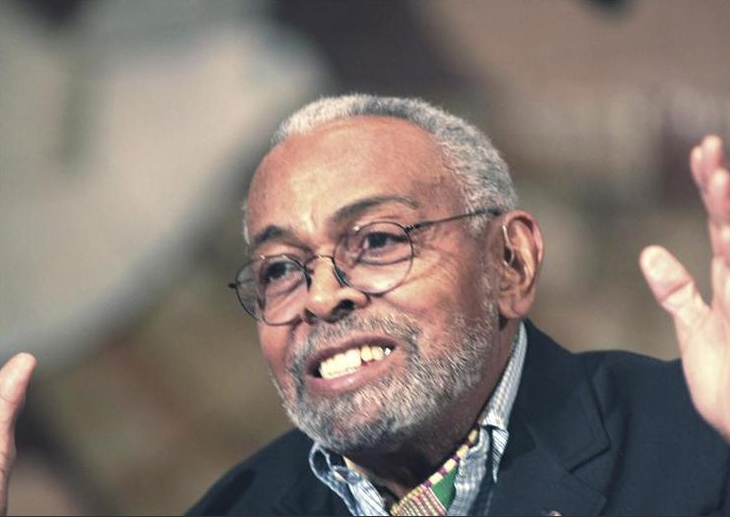

LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) and Larry Neal – “Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing”

Jones and Neal compiled poems, short stories and plays from over 70 Black writers, including themselves, dealing with the search for a definition of the Black sensibility among the harsh realities of the modern world. Certainly, 1968 introduced harshness on a new level and it would appear these writings were curated as a balm. Even as perspectives of the various writers differed (e.g., Jones did not favor the non-violent philosophy), the struggle and the goal were shared. Jones’ work was also included in “I Am the Darker Brother: An Anthology of Modern Poems by Negro Americans,” published the same year.

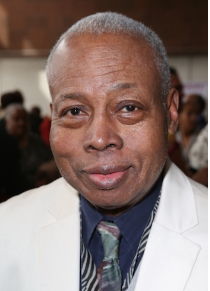

Ed Bullins – “Goin’ A Buffalo”

Ed Bullins worked in a style that he called “Black-Oriented Realism” through which he endeavored to depict life truthfully in his plays without attempts at resolution. “Goin’ A Buffalo” detailed a journey in which each character struggled to break the cycle of violence that had come to define their lives so that they may start again.

Bill Gunn – “Johnnas”

Two years before contemplating integration in urban life through his 1970 screenplay “The Landlord,” Bill Gunn’s third play, a one-act entitled “Johnnas,” premiered in 1968. Subsequently adapted and produced as a television special, it earned an Emmy.

Gene Taylor – “Why? (The King of Love is Dead)”

Gene Taylor, an accomplished jazz double bassist who toured and recorded with Nina Simone from 1966 to 1968, wrote this song, which Simone famously performed tearfully at Westbury Music Festival just three days after Dr. King’s death.

Hal Bennett – “The Black Wine”

Esteemed author Hal Bennett would write a story entitled “The Ghost of Martin Luther King,” and his 1970 novel, “Lord of Dark Spaces,” explored the insecurity of a nation in the wake of MLK’s death and the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement. “The Black Wine” however, published the year of the tragedy, explores the journey of a young man growing up, scarred by inequality, discrimination and violence.

Lorraine Hansberry – “To Be Young, Gifted and Black”

Although Hansberry died three years earlier, this successful Broadway play based on her autobiographical writings received its production debut in 1968. It was the first play on Broadway written by a Black woman, and its emergence at such a time rightly prompted audiences to ruminate on the spirit, ingenuity and brilliance of the young, gifted and Black who would be gone too soon.

In times of tragedy, art can heal, and it can honor. Reviewing and reflecting on such works brings the reader — or in the case of plays and songs, the listeners and viewers — that much closer to the honoree being celebrated, as well as the hope and dreams by which he was inspired. In that way, art leaves us with something more than loss.