In the tradition of our ancestors, again and at the beginning of this new year of our people 6263 AFE, we pause and pay rightful homage to the beautiful, strong and unbreakable bridges, past and present, that carried us over.

We give thanks for the seeds and fields of good sown and harvested in our lives and the world, and we think deep about the awesome meaning of being African and human at this critical juncture of African and human history and indeed the history of the world itself and all in it. And likewise, for now and the coming year, we wish for our people everywhere and always “blessings without number and all good things without end.”

And as we say, especially during Kwanzaa and this time when the edges of the years meet, reflecting a special concern for the world and all in it, we wish for our people, African people, and humanity as a whole, “all the good that Heaven grants, the earth produces and the waters bring forth from their depths.”

For indeed, the world and all in it is a shared good for all peoples and all beings and it is appropriate and important that we not only make this wish, but commit ourselves to living the lives, doing the work, and waging the struggle vital to realizing this inclusive goal and good for the world and all in it.

This means that we must be clear about our identity, purpose and direction. Building on the teachings of our honored ancestors, we are, at this time of the meeting of the edges of the year, to sit down, meditate on the awesome meaning and mission of being African in the world, measure ourselves in the mirror of the best of our culture, and then recommit ourselves to the kinds and quality of practices this requires.

This practice of deep thinking about ourselves and our lives, work and struggles in the world is a part of the celebration of Kwanzaa. For on the last day of Kwanzaa, January First, which is Siku ya Taamuli, the Day of Meditation, we are to engage in this practice. Indeed, we are to stop the rushin’ and runnin’, the hustle, bustle and busyness associated with celebrations, holidays and rightful pursuits of happiness and pause, be still and be at peace and answer three framing and foundational questions: who am I; am I really who I am; and am I all I ought to be?

To answer the question “who am I” is to locate ourselves in the midst of an ancient and ongoing lived and living tradition of human excellence and achievement, and self-conscious struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves and bring and sustain good in the world. To answer the question of “am I all I ought to be” is to reject the masking of our Blackness and the mimicry of Whiteness, and to defiantly and audaciously be ourselves and free ourselves in various and essential ways.

To answer the question of “am I all I ought to be” is to affirm that African means excellence in every way, and to constantly bring forth the best of what it means to be African and human in the world. And this recognition and respect of our excellence and unique and equally valid and valuable way of being African in the world has not a hint or hair breadth of the radical evil and rank odor of the White supremacist, racial and religious concepts and practices of our oppressor.

Surely, we must also understand and assert ourselves in our identity as a key moral social vanguard in this country and the world whose struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves is a critical model and mirror, an essential example and measure for liberation struggles to expand the realms of freedom and justice in this country and the world.

Thus, to answer the question “who am I” is, of necessity, to define ourselves as a people in oppression and resistance, a key moral and social vanguard indispensable to the reimagining and reconstructing of this country in ways that practice and promote an inclusive freedom, justice and the sharing of common and necessary goods for life, living and flourishing for all peoples everywhere.

It is a Kawaida understanding rooted in the sacred teachings of our ancestors, in the Husia and Odu Ifa, that we are chosen by both history and heaven to bring good in the world and not let any good be lost. Thus, in these times of great suffering and uncertainty, of sustained systemic violence against our lives, personhood and peoplehood, and the persistent pathology of racist and capitalist oppression in its savage and subtle forms imposed and inflicted on us, others and the world, we must not be confused or complacent about who we are and what we are morally obligated to do. Indeed, we must continue the struggle, keep the faith and hold the line.

For our history, culture, current conditions and strategic position at the bottom in the belly of the beast, place an awesome demand and obligation on us. Thus, we are confronted with clear choices, to be ourselves and free ourselves or be a contemptible caricature of the dominant group, seeking a comfortable position in oppression, kneeling before the idols of the tainted wealth and toxic power of our oppressor.

We can hug our chains and wear them as jewelry and representative of riches and living large or break them in the pursuit of real liberation and justice. And we can remain marginalized and mouth the false claims of democracy, freedom and justice by the oppressor or we can through righteous and relentless struggle alter the social agenda and redraw the map of life in America, yielding an inclusive and equitable representation and sharing of resources and good for everyone.

Central to all that is said and suggested above, we must not become despondent or be overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of the problem and the moral callousness and social madness of society. Indeed, in the worst of winter, we must remember to endure and struggle until spring emerges producing new life and promising summer. And in the midst of the midnight and evil of oppression, we must lift up the light that lasts, our moral and spiritual principles as a lived and living tradition. In a word, no matter what and nevertheless, we must still bloom Blackly in the whirlwind and demanding times.

This is the sacred teaching of our honored ancestor Nana Gwen Brooks as I read and interpret her essential and enduring message to us in her poem “The Second Sermon on the Warpland”. It’s a message reminding us of our sacredness, soulfulness, resilience and resourcefulness. It is a parallel and companion message to Nana Howard Thurman’s teaching that we, as a people, have within us the capacity to “ride the storm and remain intact” and to the teaching of Nana Nannie Burroughs that we can endure and accomplish “the wholly impossible” against overwhelming odds.

And it is a message resembling the metaphoric assertion of durability and adaptive vitality in the sacred teachings of the Husia that in our determination to live and flourish, we must be those who are “not wet by water or burned by fire”.

Nana Gwen Brooks tells and teaches us in her beautifully poetic way how we should see and assert ourselves in these most dangerous, difficult, deadly and demanding times. We are a special people with a special role and as I read her, she wants us to recognize and respect the beauty of our Blackness, our sacred, soulful, resilient, creative and resourceful selves which I see as central to playing our role as a key moral and social vanguard.

She speaks of our equal dignity and duty to endure and overcome “the cold places” and not follow the path of “the easy man”, but to dare live against the odds and in spite of the obstacles confronting us.

Recognizing that we often feel alone in our struggle to bring good in the world, she counsels us saying, “it is lonesome, yes / for we are the last of the loud.” And yet she says, “Nevertheless live / conduct your blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.”

And if we bloom and bloom Blackly in the whirlwind, we will find Nana Marcus Garvey and all the numerous ancestors there as he promised, leading us to our inevitable victory. And as Nana Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune taught, this ultimately means daring to remake not only this country but the world, remaking it in ways that respect and reflect the equal dignity of all and the hard won achievement of shared good of the world and for the world and all in it.

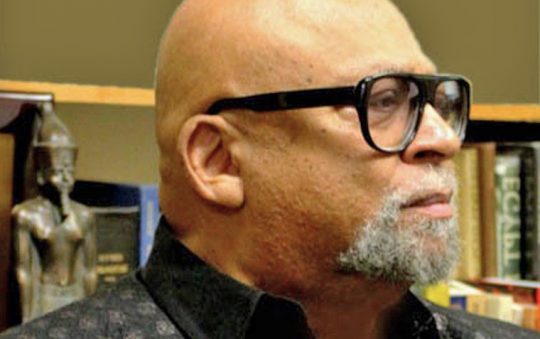

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture, The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good Into the World and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.