Few Americans believe there has been significant progress over the last 50 years in achieving equal treatment for Black people in dealings with police and the criminal justice system.

Most Americans across racial and ethnic groups say more progress is necessary, according to a new poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. But Black Americans, many whom may have held hope in Democrats’ promises on racial justice initiatives in 2020, are especially pessimistic that any more progress will be made in the coming years.

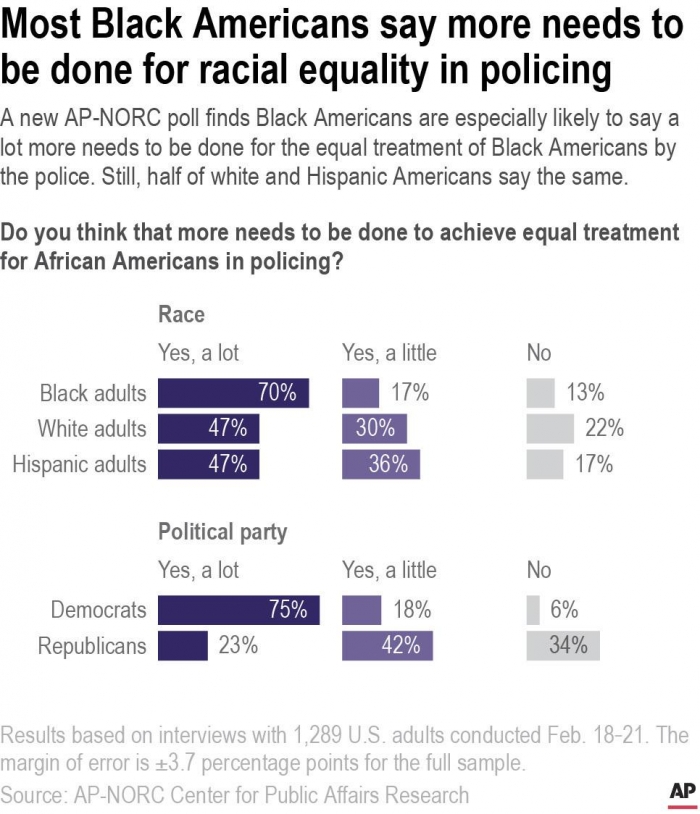

Overall, only about a quarter of Americans say there has been a great deal or a lot of progress in achieving racial equality in policing and criminal justice. Roughly another third say there’s been “some” progress. An overwhelming majority of adults say more progress is needed for racial equality, including about half who say “a lot” more.

“There’s more attention around certain issues and there’s a realization — more people are waking up to a lot of corruption in the system,” said Derek Sims, a 35-year-old bus driver in Austin, Texas, who is Black. He considers himself more optimistic than pessimistic that change will happen.

However, Sims said: “People don’t really want to come together and hash out ideas. There’s just too much tribalism.”

Among those who think more progress is needed on achieving fair treatment for Black Americans by police, 31% say they are optimistic about that happening in the next few years, while 38% are pessimistic. Roughly another third say they hold neither opinion.

Only 20% of Black Americans who think more needs to be done are optimistic; 49% are pessimistic.

The AP-NORC poll results reflect what some criminal justice advocates have warned elected leaders about for more than a year: that unless something definitive is done soon to begin transforming police and the criminal justice system, it could become more difficult to mobilize dissatisfied Black voters in the midterm elections.

And already, Democrats’ pivot to the center on racial justice issues has given advocates pause. During his first State of the Union address earlier this month, President Joe Biden said the answer to reported rises in violent crime “is not to defund the police.”

“The answer is to fund the police with the resources and training they need to protect our communities,” Biden said in remarks that have been seen as a clear disavowal of some Black Lives Matter activists’ rhetoric.

In 2020, following the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, many Americans across racial and ethnic backgrounds called for criminal justice reforms in nationwide protests. On Capitol Hill, consensus on reforms, via the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, has not been reached nearly two years later.

“What we saw from the George Floyd case, we in the Black community know that those officers were found guilty because of the outcry,” DeAnna Hoskins, president and CEO of JustLeadershipUSA, a New York-based nonprofit criminal justice reform advocacy group, told the AP.

“The only reason why you get results is because there was an outcry that included Black and white people. You’ve got a much larger voter base saying something has to be done,” she said.

Due to vastly different lived experiences, it’s been harder to get Americans across racial and ethnic groups to sustain their outcries and demand an end to systemic racism, Hoskins added.

The poll shows there is common ground on the issue across racial and ethnic groups, but also suggests there is urgency felt among Black Americans more than white Americans. More white Americans than Black Americans say there has already been significant progress toward racial equality in policing, 30% vs. 10%. Among Black Americans, 40% say there has been no progress at all.

And while at least three-quarters of white and Black Americans say more progress is needed, Black Americans are much more likely than white Americans to say a lot more needs to be done, 70% vs. 47%.

Last year marked 50 years since a war on drugs was declared in America. The bipartisan public policy at the federal and state levels saw the nation’s incarceration rate skyrocket to the highest in the industrialized world. Black Americans, in particular, bore the brunt of police militarization and laws that imposed mandatory minimum prison terms.

There were also post-incarceration consequences, such as losing the right to vote, being barred from public housing and certain college financial aid programs, and struggling to find employment with a felony record.

Compared with views on policing and criminal justice, Americans are more likely to think there has been significant progress over the last 50 years in achieving equal treatment for Black Americans in political representation, access to good education, access to good health care and access to good jobs. And there’s more pessimism about progress over the next few years in policing and criminal justice than in the other areas.

Heydy Maldonado, 30, blames how crime is covered by TV and print news outlets — which she said often frame violence in a way that suggests it is only endemic to Black and Hispanic communities — for the lack of hope in reforms.

“We get targeted,” said Maldonado, whose family is Honduran and Salvadoran. “I’m sure there’s more crime out there, and it’s not just our race, it’s not just people of color. It’s an ongoing battle.”

“I do feel like we need to be united and speak to each other and keep fighting for change,” she added. “Eventually, hopefully, this could all be a thing of the past.”

___

The AP-NORC poll of 1,289 adults was conducted Feb. 18-21 using a sample drawn from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is plus or minus 3.7 percentage points.