Sidney Poitier

Mr. & Mrs. Poitier (Joanna Shimkus Poitier & Sidney Poitier)

The elegant Sidney Poitier

President Barack Obama and Sidney Poitier

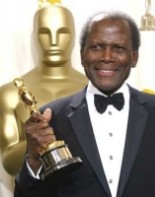

SIDNEY POITIER

“The first Black man to win an Academy Award for a starring role”

While accepting an honorary Academy Award in 2002, Sidney Poitier delivered the following remarks, in part: “I arrived in Hollywood at the age of 22 in a time different than today’s, a time in which the odds against my standing here tonight 53 years later would not have fallen in my favor. Back then, no route had been established for where I was hoping to go; no pathway left in evidence for me to trace; no custom for me to follow. Yet, here I am this evening at the end of a journey that in 1949 would have been considered almost impossible, and in fact, might never have been set in motion, were there not been an untold number of courageous, unselfish choices, made by a handful of visionary American filmmakers, directors, writers and producers. Each with a strong sense of citizenship responsibility to the times in which they lived; each unafraid to permit their art to reflect their views and values, ethical and moral, and moreover acknowledge them as their own. They knew the odds that stood against them and their efforts were overwhelming, and likely could have proven too high to overcome. Still those filmmakers persevered, speaking through their art to the best in all of us, and I benefitted from their efforts; the industry benefitted from their efforts; America benefitted from their efforts. And in ways large and small, the world has also benefitted from their efforts…. “

The award was given to him for his body of work … work done to better the industry, for his influence among filmmakers around the world; for his extraordinary performances and unique presence on the screen, and for representing the industry with dignity, style and intelligence. Â

CAT ISLAND AND MIAMI

Life started for Sidney Poitier en route to Miami from Cat Island in the Bahamas and he returned to the Bahamas to be its ambassador to Japan; along the way, he picked up an Academy Award. That journey was as amazing as it was, and still is, real.

Growing up the son of a poor dirt farmer young Poitier did not have much to look forward to; having little formal education further diminished his chances of worldly success and made his future looked less promising. There were not many or any light at the end of tunnel to look forward to, or pots of gold at the end of the rainbow to reach for, on Cat Island. Rainbows came as a result of the reflection of light after rainfall, and that’s all – nothing to do with gold or prosperity.

When he was a teenager, his parents – wanting a better life for their son – sent him to Florida to live with a relative, where with all its bright lights and modern conveniences that young Poitier was unaccustomed to on Cat Island, he became conscious of racism. It was in Miami, Florida that the young Bahamian Cat Islander was first introduced to and experienced the racial divide that separated Blacks and Whites. Though in Cat Island he was poor, the environment was all Black and consisted of equal opportunity poverty. His basic value system was diametrically opposite of what White people expected of Black people. (Cat Island’s mores collided with those of America, in Miami). There the wretched treatment Poitier received propelled him to leave town in a hurry, and off he went on a railroad car heading anywhere as long as it was out of the city.Â

Â

NEW YORK AND HOLLYWOOD

After a pit stop in Georgia, he ended up in New York City, and Harlem. Poitier’s location had changed but not his condition; he was still broke, hungry, out-of-doors and further away from home, not knowing anyone. He had the uncanny instinct to survive and proceeded to arrange his life towards this basic instinct – survival, the hereditary pearl of wisdom he had gotten from his mother’s emotional form of discipline. He did menial jobs and slept wherever he could lay his body for the night – on rooftops – and worked in kitchens (obviously not as a chef), but determined to find better opportunities to enhance his future. In addition, coming from a tropical island, Poitier was not prepared nor had he ever experienced the harshness of winter. Â

The U.S. Army literally took him in out of the cold though his tolerance for Jim Crow and military discipline was non-existent. By eighteen, an age when most persons begin their military enlistment, Poitier had already been in, and out of the military. He returned to the New York he had left but nothing there had changed for him.

The next opportunity he encountered landed him at the American Negro Theatre. Unlike the army, this time he brought along seemingly insurmountable baggage. Poitier had no formal education – he could hardly read – and he had a Bahamian accent. In order to upgrade his chances of becoming an actor, he became the janitor of the theatre. He surmised that being around acting/the theatre, some of it may rub off through osmosis.

At the theatre and in Harlem in general, he met lifelong friends and associates including a “funny talking” young man like himself named Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee, Ivan Dixon, William Marshall and Brock Peters. He kept trying after being rejected, until he scored on stage in “Lysistrata” which was followed by being an understudy in a road show, “Anna Lucasta.” (In later years, Belafonte would say that Poitier, “put the cinema and millions of people in the world in touch with a truth about who we are. A truth that could have for a longer time eluded us had it not been for him and the choices he made.”)

His next project was his first film, “No Way Out” that he referenced in his remarks, “I arrived in Hollywood at the age of 22….” (1949), for which he was reportedly paid $3000 – a tidy sum at that time. It came out in 1950 and it set the tone for his next movie, “Cry, the Beloved Country” which was filmed in apartheid South Africa. Though he had been to London, Hollywood and South Africa, his home base was in New York.  That same year (1950), he married Juanita Hardy and the union produced four girls: Beverly, Pamela, Sherri and Gina.

His first movie was shown in theaters on Cat Island and when he returned home, his parents “forgave all his sins” – not writing for eight years. (The people in the Caribbean believed that everyone in America is either rich, well-off or at least doing better than those they left behind; and to a certain extent, relatively speaking, they were correct. So when they wrote to their relatives in America, a shopping list usually accompanied the letter. And when relatives from America would return home to the Caribbean there were great expectations of money and gifts.)  Â

Between 1952 and 1958, Poitier made nine films with some of Hollywood’s leading White men at the time including Jeff Chandler in “Red Ball Express,” Dane Clark in “Go Man Go,” Glenn Ford in “Blackboard Jungle,” Rock Hudson in “Something of Value” and Clark Gable in “Band of Angels.” He also teamed up with Eartha Kitt in “Mark of the Hawk,” and received his first nomination for a BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) Award for the leading role in “Edge of the City.”

Things were rough financially and he tried his hand opening a little rib joint, “Ribs in the Ruff,” in Harlem. Around the same time, Poitier was introduced to his future agent Marty Baum; the association was not always smooth since he would refuse parts that did not fit his criterion or measure up to the values that were instilled in him by his father. He was a dishwasher in-between jobs, but because of his values and his “stick-to-it-ive-ness,” he eventually won over Baum, as his agent, and gained solid footing in Hollywood. His acting career also gained some upward mobility.          Â

RISING TO THE TOP

When “The Defiant Ones” was released in 1958, Poitier’s standing in Hollywood increased; he was nominated for an Academy Award as best actor, the first for an African American up to that time, as referenced in his remarks, “…in a time different than today’s, a time in which the odds against my standing here tonight 53 years later would not have fallen in my favor….”Â

He returned to Broadway in 1959 for “A Raisin in the Sun” for which he received a Tony Award nomination as best actor. He then went on to do the film version of the same named piece in 1961. Poitier continued to pioneer the way for future generations of African American actors and actresses to follow. He was looked at as the quintessential Black actor and his star quality was continually rising. On the other hand, whatever he did or did not do was looked at by White people as representative of Black people; he was carrying Black people on his back, on and off the screen.Â

Movies and nominations continued, and public controversies arose – some meaningful and others, a flash-in-the-pan. Back when Poitier was making “Blackboard Jungle,” his friendship with Paul Robeson and Canada Lee came into question and he was asked to sign a loyalty oath (whatever, that was). Poitier refused, as a matter of principle, and the matter died a natural death. He received two Golden Globe Award nominations for “Porgy and Bess” (1959) and “A Raisin in the Sun” (1961).

The Civil Rights Movement was heating up, and Poitier and Belafonte eventually played important roles assisting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the movement. They donated time, energy and money, and participated in the 1963 March on Washington. As time went along, Poitier was becoming intimately familiar with the inner workings of behind-the-scene realities, politics in Black and White, and the liberal/conservative, leftwing/rightwing stuff.

As the 60s began, Poitier solidified his position as an actor; he made several quality movies during that period such as “All the Young Men” (1960), “Paris Blues” (1961), “Pressure Point” and “the Long Ships” (1962).

THE ACADEMY AWARD AND BEYOND

The roles he accepted catapulted him into an unimaginable sphere for a Black man in Hollywood which culminated in 1963 with “Lilies of the Field” for which he received the coveted Academy Award as best actor, and also the Golden Globe Award. He was the first Black man in history to win the Academy Award and as he remarked in 2002, “…. Yet, here I am this evening at the end of a journey that in 1949 would have been considered almost impossible….”

His career continued to flourish however, his personal life took a downturn as he and his wife of 15 years, Juanita Poitier, divorced in 1965. But quality roles kept coming and his name on the marquee was a box office magnet. From 1960 to 1979, at least one Poitier movie – and sometimes more than one – was released each year, with the exception of 1976. In 1967, three of his movies were released, “To Sir With Love,” “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.” That year he was a box office giant; he insisted on a percentage of the box office, the first Black to accomplish that feat. The second and the third of those movies gave some in the Black community moments of satisfaction and moments of derision respectively.Â

Poitier played an urban-trained Philadelphia detective visiting his mother in Sparta, Mississippi in “In the Heat of the Night.“ He was picked up for murder. There were two instances in the movie which gave Black audiences a rise – movie satisfaction. The first: At one point in a heated verbal exchange, the White racist sheriff asked him, “…..what do they call you, boy?” And Poitier answered forcefully, “They call me Mr. Tibbs!”  The second: He went to a rich White bigot’s home to question him about the murder. The man felt so degraded at the thought of being questioned by a Black man – detective or not – that he slapped Poitier who immediately slapped him back in the presence of the sheriff, who did nothing. The movie spawned two sequels, “They Call Me Mister Tibbs” (1970) and “The Organization” (1971) and a television series.Â

In “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” the flack came from both sides, Blacks and Whites. Some Blacks were saying that Poitier was a sellout and that he was not militant enough. Some Whites were saying that Katharine Houghton, with whom Poitier had an on-screen relationship, was degrading her race. The film received mixed reviews when it came out. At that time, America was in a state of social turbulence. But an important part of the movie went virtually without critical review. Poitier and his father were having a heated discussion about life in Black and White. He told his father, “… you think of yourself as a colored man. I think of myself as a man.” The significance of that exchange never got the focus it deserved.

Dr. King serenaded Poitier in 1967 and said, “He is a man of great depth, a man of great social concern, a man who is dedicated to human rights and freedom. Here is a man who, in the words we so often hear now, is a soul brother.”  Poitier had created a model for others to follow without any precedent and he helped change stubborn racial attitudes that were prevalent in America as he remarked in 2002, “…. Back then, no route had been established for where I was hoping to go; no pathway left in evidence for me to trace; no custom for me to follow…” He built bridges and opened doors for others, as others had done for him.

In 1969, Poitier made a movie, “The Lost Man” in which he played opposite Joanna Shimkus; seven years later, she became Mrs. Poitier. The union produced two daughters: Sydney and Anika. In the 1970s, though he returned to the Bahamas to live, he continued to make movies in the United States. It is important to note that throughout his career, as an artist in the spotlight, Poitier never “konked” his hair; it was always natural.

DIRECTOR, AUTHOR & LEGACY

With “Buck and the Preacher” (1972), he starred in, along with Belafonte and Dee, and made his debut as a director. Then along with Steve Mc Queen, Paul Newman and Barbra Streisand, Poitier formed First Artist Production Company which released his next four films. For the rest of the 1970s, he starred in, along with his counterpart on television, Bill Cosby, and directed three successful comedies: “Uptown Saturday Night” (1974), “Let’s Do It Again” (1975) and “A Piece of the Action” (1977).  He also starred in “the Wilby Conspiracy,” a film dedicated to exposing the horrors of apartheid in South Africa.

After 1977, he took a ten-year hiatus from acting though he continued to direct. He directed four films between 1980 and 1990. His next film was “Shoot to Kill” (1988) and his last film on the big screen (non-documentary) was “The Jackal” (1997).

During the 1990s up to 2001, Poitier made several movies for television. They included “Separate But Equal” as Thurgood Marshall; “Mandela and De Klerk” as Nelson Mandela and his last was “The Last Brick-maker in America.”

Poitier has written two autobiographies: “This Life” (1980), and “The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography” (2000). The latter was selected as one of Oprah’s Book Club and a New York Times Bestseller. “Life Beyond Measure – letters to my Great-Granddaughter” (2008) was his third book. Â

Since 1997 he has been the Bahamian ambassador to Japan and is also the ambassador of the Bahamas to UNESCO.

It has been reported that Poitier would not be appearing in front or behind the cameras anymore and is indeed retired. However, his legacy as a pioneer in Hollywood, a humanitarian and a diplomat, has left a body of work and accomplishments that may never be duplicated. His talent, integrity and style have broken down social barriers in every field of endeavor that he has undertaken. Poitier defied racial stereotyping and has remained one of the most respected figures on and off the screen.

He speaks Russian fluently, has an honorary doctorate degree from Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania and was the first black actor to place his autograph, hands, and footprints in the cement at Grumman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. He has four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

In addition to his two Academy Awards, Poitier has received the American Film Institute Lifetime Achievement and the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Awards, the Kennedy Center Honors, two NAACP Image Awards and a Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album. President Barack Obama recently awarded Poitier the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor at a White House ceremony.

He closed his acceptance remarks at the 2002 Academy Awards thus: “….I accept this award in memory of all the African American actors and actresses who went before me in the difficult years, on whose shoulders I was privileged to stand to see where I might go. My love and my thanks to my wonderful, wonderful wife, my children, my grandchildren, my agent and friend, Martin Baum, and finally, to those audience members around the world who have placed their trust in my judgment as an actor and filmmaker. I thank each of you for your support through the years. Thank You!”