I am humbled by the legacy that Sidney Poitier has left. Imagine the sheer will that is required to shatter all of the obstacles that were tossed into his path. The hatred of African Americans in the United States of America has never left this stolen land, but in the ’20s, achieving any kind of equality seemed as distant as touching the stars.

Sidney Poitier was a part of that generation, living in that dark era, when White folks kept their proverbial foot on the literal necks of our people. He came into the world on February 20, 1927, and departed (God, Bless the dead), on January 6, 2022, at the age of 94.

And although I am not a religious woman, this Bible verse, which is found in Matthew 25:23, keeps ringing in my head, it goes: His Lord said to him, “Well done, good and faithful servant; you have been faithful over a few things, I will make you ruler over many things. Enter into the joy of your lord.”

Let’s get down to brass tacks and speak plainly. Mr. Sidney Poitier put his foot in it. And by “in it” I mean he’s in the history books as the first African-American actor to win the Academy Award in the Best Actor category, in 1963, for the film “Lilies of the Field,” and he’s on record saying that he felt “as if I were representing 15, 18 million people with every move I made.” Such is the burden of daring to shake off the shackles of institutional discrimination.

For many, Mr. Poitier will be remembered for his portrayal of determined, dignified heroes in classic films like “In the Heat of The Night,” “To Sir With Love,” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” all of which firmly established him as Hollywood’s first African American movie star.

But Mr. Poitier was much more than an actor, using his notoriety, he rose to prominence when the Civil Rights Movement was beginning, and his choice of roles seemed to reflect his own goals in the struggle. The word most used when describing his performances is dignity and somehow, he gave you the feeling that he was a superhero, delivering his power, and grace on and off-camera.

In the era of civil rights, fighting for real, positive change was a necessity and Mr. Poitier’s work ethic quickly became synonymous with African American excellence. And we all know, too well, that our people can’t be mediocre that’s part of White privilege and mediocrity is that tricky mechanism that allows the white race (usually, white men) to continue to fail, up.

This was the 50s and 1960s and his characters simmered with that repressed anger our people (sadly) knew all too well. Here, they watched this deep, chocolate-hued man respond to injustice with a dignified, warrior-like determination. And get, some accused Mr. Poitier of being an “Uncle Tom” in the 1960s but this intelligent man, who had experienced hardship, understood that as Hollywood’s sole African-American leading man, he was being viewed through a very different lens.

Naturally, as an actor he longed to play different kinds of roles, but Mr. Poitier could see the bigger picture in a way many during this era, could not.

“It’s a choice, a clear choice,” Mr. Poitier revealed in an interview, in 1967. “If the fabric of the society were different, I would scream to high heaven to play villains and to deal with different images of Negro life that would be more dimensional. But I’ll be damned if I do that at this stage of the game.”

Back to the brass tacks again — Mr. Poitier was one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood, a big money-making box-office draw and

ranked fifth among male actors in Box Office magazine’s poll of theater owners and critics; just behind Paul Newman, Lee Marvin, Richard Burton, and John Wayne.

But despite proving his worth, Mr. Poitier often found himself stuck, playing the same kind of roles – those of the saints – but remember, that during this period in cinematic history, it was a gigantic step up and away from more demeaning roles that Hollywood had offered him in the past.

To wit, in the film “No Way Out” (1950), his first, meaty role, he played a physician persecuted by an angry, racist patient, and in “Cry, the Beloved Country” (1952), he played a young priest.

In“Blackboard Jungle” (1955), he played a troubled student trying to navigate through a tough New York City public school. In “The Defiant Ones” (1958), which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor, he was a prisoner on the run, handcuffed to a fellow convict (a White racist) played by Tony Curtis.

It was in 1964 that he earned his Oscar for the modest budgeted “Lilies of the Field,” playing a handyman helping a group of German nuns build a church in the Southwestern desert.

“I can tell you what I think the flak was about. For a long time, I got all the jobs — one picture after another after another. And the roles I played were very unlike the average Black person in America at the time. The guy always had a suit, a tie, a briefcase! He was a doctor, lawyer, police detective. Middle-class. The characters weren’t reflective of the diversity of Black life. I don’t know that I wouldn’t have had resentments myself, had I been an actor on the outside looking in,” said Mr. Portier on criticism of his on-screen persona, from a 1995 interview with the Washington Post.

Mr. Poitier’s profile kept rising, 1967 Mr. Poitier appeared in three of Hollywood’s top-grossing films: “In the Heat of Night,” where he played opposite Rod Steiger, a bigoted sheriff that Virgil Tibbs, a Philadelphia detective, played by Mr. Poitier, must work on a murder investigation in Mississippi. It’s in this film that he utters one of his favorite lines, where he declares, “They call me Mr. Tibbs!”

His success kept growing, playing a concerned teacher in a tough London high school in the film, “To Sir, With Love,” and in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” an important, taboo-breaking film about an interracial couple, he plays the doctor who tests the liberal principles of his prospective in-laws, played by Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn.

How did it all begin? Mr. Poitier was born in Miami, but he grew up in the Bahamas, the youngest of nine children. He was so poor that he wore clothing made from flour sacks. His parents traveled regularly to sell their tomato crop. After Florida banned the import of Bahamian tomatoes, eventually his father moved the family from Cat Island to Nassau in 1937.

Times were bitterly hard for the family and at the age of 12,

Mr. Poitier quit school to work as a water boy for a crew of pick-and-shovel laborers. Restless, he began to get into trouble, so he was sent to Miami, at the age of 14, to live with a married brother, Cyril.

It was in Miami, that Mr. Poitier received the rude awakening of segregation something – he didn’t experience growing up on Cat Island. He lasted a year in the Sunshine State and relocated to New York with less than $5 in his pocket and took jobs working as a ditch digger, delivery man, and dishwasher. During a race riot in Harlem, he was shot in the leg. Times were so challenging that he would save his hard-earned nickles so on cold nights he could sleep in pay toilets.

In 1943 in desperation, Mr. Poitier lied about his age and enlisted in the Army, where he became an orderly in the 1267th Medical Detachment at a veterans hospital in Long Island. In quick order, he discovered that military life was not for him and he faked a mental disorder and was granted a discharge in 1945.

Back in New York, he read an announcement, in The Amsterdam News, that the American Negro Theater was looking for actors. His first audition was a flop. Frederick O’Neal, a founder of the theater, was not impressed by his poor reading skills or his heavy, West Indian accent and suggested that he get a job as a dishwasher.

Determined, Mr. Poitier purchased a radio and practiced speaking English in the crip, American accents of the staff announcers. A fellow dish washer took pity on him and helped him learn to read. Soon,

Mr. Poitier won a place in the theater’s acting school, where he volunteered to work as a janitor without pay.

His hard work paid off, when another actor at the theater, Harry Belafonte, was a no-show for a rehearsal that was attended by a Broadway producer, and Mr. Poitier stepped into the role and was later given a part in an all-Black production of “Lysistrata” (1946).

Other theater jobs came including the road production of “Anna Lucasta” and “No Way Out.” Film and television roles begin to fall into his lap but very few, and Mr. Poitier was balancing his meager acting work with odd jobs.

Love called, and in 1951, he married Juanita Marie Hardy, a dancer but he divorced in 1965 with the couple having four daughters, Beverly, Pamela, Sherri, and Gina. In 1976, love called again, marrying

Joanna Shimkus, his co-star in “The Lost Man” (1969) and they had two daughters, Anika and Sydney.

Mr. Poitier’s credits are long but it was his purpose to help change racial tolerance in his backyard — Hollywood and he was successful.

It’s on record that the film, “The Defiant Ones,” was one of Mr. Poitier’s favorite films, but to land the part he had to deal with Samuel Goldwyn, who was hiring the cast of “Porgy and Bess.” Once Harry Belafonte turned down the role of Porgy considering it demeaning, Mr. Goldwyn wanted no one else but Mr. Poitier, who also thought that the musical was an insult to African-Americans.

In his memoir, “This Life” (1980), he talks about the tactics that Goldwyn used to secure him in the role of Porgy, making it so that

the director Stanley Kramer would not hire him for “The Defiant Ones.” Pressed, and against the wall, Mr. Poitier, stepped into the role. And despite his longstanding commitment to racial justice and his time spent working in the civil rights movement, some critics, at the time, accused him of kneeling before the white establishment.

In 1959 Mr. Poitier returned to Broadway in Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun,” where he received positive notices. Mr. Poitier repeated the role in the 1961 film version of the play.

Time and hard work made important inroads and the rise of African American filmmakers like Melvin Van Peebles and Gordon Parks who blazed into the industry in the late 1960s and early ’70s helped open new opportunities.

Now in his 40s, Mr. Poitier turned to directing and producing films, starting with the romantic comedy “For Love of Ivy,” (1968), in which he starred with Abbey Lincoln. In 1969 he joined Paul Newman and Barbra Streisand to form the production company First Artists, and he directed the western “Buck and the Preacher” (1972), playing opposite Harry Belafonte, and a series of comedies, notably “Uptown Saturday Night” (1974) and “Let’s Do It Again” (1975), and “Stir Crazy” (1980), with Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder.

As a director, Mr. Poitier’s other credits include the comedy “Hanky Panky” (1982), with Gene Wilder and Gilda Radner, and “Ghost Dad” (1990).

Following the trend, Mr. Poitier stepped into roles in several action films and thrillers like, “Shoot to Kill” (1988), “Little Nikita” (1988), and “Sneakers” (1992). Like hundreds before him, he turned to

television which provided him with two of his most recognizable roles.

First, in 1991 he appeared in the lead role in the ABC drama “Separate but Equal,” a dramatization of the life of Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. In 1997 he played Nelson Mandela in “Mandela and de Klerk,” a popular television movie that focused on the final years of Mr. Mandela’s imprisonment by the white-minority government in South Africa, with Michael Caine in the role of President F.W. de Klerk.

Make no mistake, the history books get it right. Mr. Poitier was about it, and although his style might have appeared low-key, he was always working to be a part of the solution.

“I was part of an influence that could be called paving the way. But I was only a part of it. I was selected almost by history itself. Most of my career unfolded in the 1960s, which was one of the periods in American history with certain attitudes toward minorities that stayed in vogue.

“I didn’t understand the elements swirling around. I was a young actor with some talent, an enormous curiosity, a certain kind of appeal. You wrap all that together and you have a potent mix.” — From a 1992 interview with the Times of London.

Mr. Poitier continued to work and influence his community, and in 2002, he was given an honorary Oscar for his career’s work in the film industry. It’s an interesting note in cinematic history, that this award was given at the same Oscar ceremony where Denzel Washington became the first African-American actor since Mr. Poitier won the best-actor award, for “Training Day.”

The accolades continued, in 1974 Mr. Poitier was knighted by Queen Elizabeth. In 1995, he received a Kennedy Center Honor and in 2009, President Barack Obama, citing his “relentless devotion to breaking down barriers,” awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“Those of us that go before you, glance back with satisfaction and leave you with a simple trust. Be true to yourselves and be useful to the journey.” — Accepting the AFI Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992.

As an author, he penned his memoir “This Life” which was followed by a second, “The Measure of a Man,” in 2000, which is subtitled “A Spiritual Autobiography,” and included Mr. Poitier’s thoughts on life, love, acting, and racial politics. It generated a sequel, “Life Beyond Measure: Letters to My Great-Granddaughter” (2008).

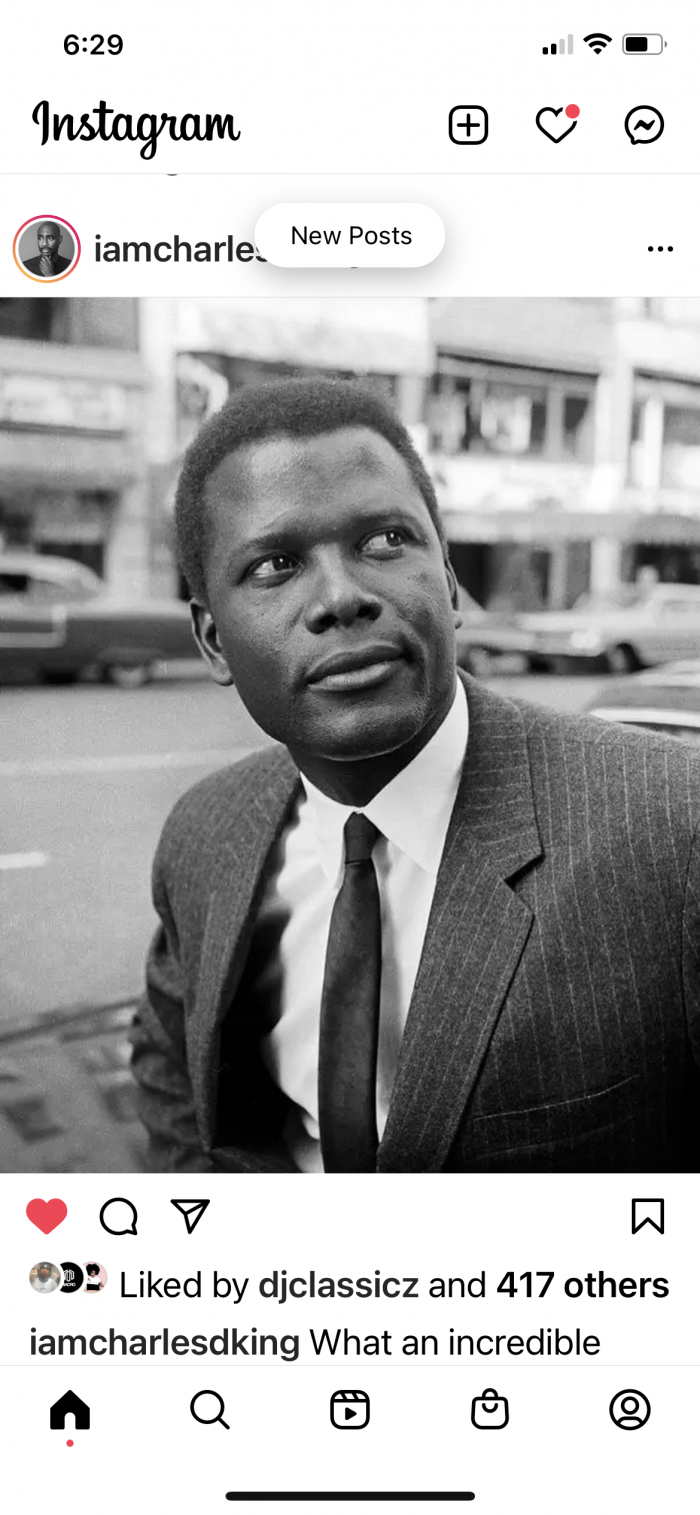

Mr. Poitier’s transition on January 6, 2022, at the age of 94, brought out an outpouring of remembrances by those that were deeply influenced by the trailblazing actor who has inspired generations of African Americans.

Via Twitter, British actor Aaron Cobham thanked him for opening “the door for so many to chase their dreams” said Charles King, CEO of MACRO on commenting on the loss acknowleged:

“We all stand on his trailblazing shoulders and will eternally be grateful for the beautiful legacy he shared with us,” and designer B. Michael opened his tweet: using a portion of Maya Angelou’s poem “When Great Trees Fall” and I echo his sentiment, because, in Truth, because Sir Sidney L. Poitier was that big tree.

Here is a statement from the Poitier family:

There are no words to convey the deep sense of loss and sadness we are feeling right now. We are so grateful he was able to spend his last day surrounded by his family and friends. To us, Sidney Poitier was not only a brilliant actor, activist, and a man of incredible grace and moral fortitude, he was also a devoted and loving husband, a supportive and adoring father, and a man who always put family first. He is our guiding light who lit up our lives with infinite love and wonder. His smile was healing, his hugs the warmest refuge, and his laughter was infectious. We could always turn to him for wisdom and solace and his absence feels like a giant hole in our family and our hearts. Although he is no longer here with us in this realm, his beautiful soul will continue to guide and inspire us. He will live on in us, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren—in every belly laugh every curious inquiry, every act of compassion and kindness. His legacy will live on in the world, continuing to inspire not only with his incredible body of work but even more so with his humanity.

We would like to extend our deepest appreciation to every single one of you for the outpouring of love from around the world. So many have been touched by our dad’s extraordinary life, his unwavering sense of decency and respect for his fellow man. His faith in humanity never faltered, so know that for all the love you’ve shown him, he loved you back.