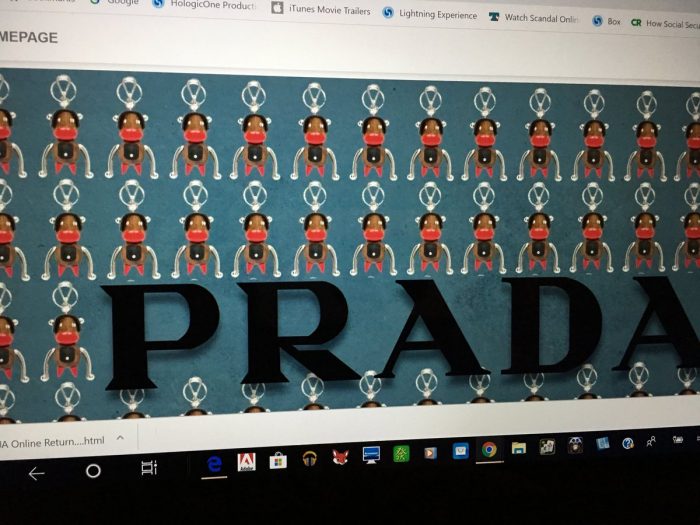

Prada S.p.A., a world renown Italian fashion house based in Milan, Italy and founded in 1913 by Mario Prada, felt the hot wrath of social media on December 14.

Chinyere Ezie, a civil rights attorney employed at the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York, posted images of a new set of keychains on her Facebook and Twitter accounts on December 13. “Thanks to #blackface @Prada, now you can take #sambo home with you for the holidays #StopRacism #StopBlackface #StopPrada,” she wrote on her Twitter account.

Four thousand retweets and over six thousand “likes” later, Prada was in hot water and confronting a full-scale public relations disaster.

Prada’s keychain items were reminiscent of blackface imagery used to degrade African Americans during the Jim Crow-era.

The images Ezie posted were from a window display in lower Manhattan. Images of Prada keychain accessories, primarily of black and brown figures with large red lips, retailed for $550.That the keychains bore an unmistakeable resemblance to many stereotypical images of African Americans, particularly in the South, wasn’t missed by many after Ezie posted.

The viral social media backlash that followed prompted the company to pull all of the items worldwide as calls for a boycott slowly built during discussions on Twitter. Prada’s first statement in reaction to the criticism on Twitter didn’t help.

“Prada Group abhors racist imagery. The Pradamalia are fantasy charms composed of elements of the Prada oeuvre. They are imaginary creatures not intended to have any reference to the real world and certainly not blackface. #Prada Group never had the intention of offending anyone and we abhor all forms of racism and racist imagery. In this interest we will withdraw the characters in question from display and circulation,” declared the company on December 14.

“I am a 53-year old white man in the south. You can Prada oeuvre all you want. I know blackface when I see it and this it,” wrote an observer of the controversy on Twitter, based in Memphis, Tenn. That sentiment to Prada’s first reaction to the criticism was common.

On December 16. Prada tried again.

“We are committed to creating products that celebrate the diverse fashion and beauty of cultures around the world. We’ve removed all Pradamalia products that were offensive from the market and are taking immediate steps to learn from this… The resemblance of the products to blackface was by no means intentional, but we recognize that this does not excuse the damage we have caused… we have learned from this and will do better,” a new Prada release stated.

On December 15, the Lawyers Committee on Civil Rights wrote on social media saying, “We’re extremely disappointed to see @Prada use racist imagery that harkens to the era of Jim Crow. Normalizing racism is dangerous. Full stop.”

“While @Prada did the right thing removing this product line, their initial choice to display such items is reprehensible. Blackface has served as a degrading depiction of African Americans. As a global fashion brand, it showed a serious lapse in judgment,” wrote NAACP President Derrick Johnson on December 16.

The incident has set off a discussion regarding diversity at the company. Prada sold over $3 billion in merchandise in 2017.