Historic baseball leagues celebrated by USPS with the release of commemorative stamps.

By Michael Brown

Sentinel Contributing Writer

Avid baseball fans and stamp collectors alike both had reason to celebrate as the United States Postal Service unveiled a pair of stamps in honor of the Negro Leagues at a recent ceremony in Kansas City.

In an ideal scene, Thurgood Marshall Jr. uncovered the two 44-cent stamps at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum July 15, tying together two major components to the lineage of the Civil Rights Movement.

Marshall Jr., vice chairman of the USPS board of governors, is the son of America’s first-black Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall. The late Thurgood Marshall became an icon in the Civil Rights Movement by challenging America’s discriminatory law of “separate but equal” in the landmark case, Brown vs. Board of Education. As a lawyer, Marshall’s arguments before the Supreme Court helped defeat legally mandated discriminatory policies in the 1954 decision.

The Negro Leagues, established in 1920, contributed in its own way to the struggle for equality by allowing Black men, barred from major league baseball, to display their athletic prowess on the field. The players, with their trademark uniforms and regular exhibitions of exciting play, garnered a sizable multi-racial fan following as they traveled to rural and urban areas throughout the United States, Canada and Latin America.

Gregory D. Baker, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, told the Associated Press, “Make no mistake about it. All these athletes were trailblazers on and off the field. Through their unsung civic endeavors, the (Negro) Leagues and their players raised awareness and started a conversation about the standards of social justice in our country for all people regardless of race or gender.”

One Negro League fan decided in 1945 to alter the course of American sports and social history by signing a Negro Leaguer to a minor league contract. Branch Rickey, Brooklyn Dodgers general manager, recruited Jackie Robinson from the Kansas City Monarchs, making him the first African American to play in the majors in the modern era (1947)-which eradicated baseball’s color barrier.

Players such as Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson and “Cool Papa” Bell were just a few of the standout performers in the Negro Leagues’ heyday. Attendance and interest waned for the Negro Leagues after the majors were integrated, and young sluggers like Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks and Willie Mays opted to sign major league contracts. The Leagues remaining teams folded in the early ’60s, leaving a legacy that still inspires many people.

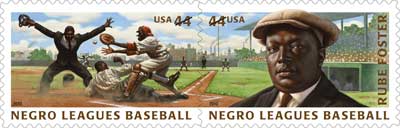

Both stamps, designed by NAACP Image Award recipient, Kadir Nelson, were put through a grueling process before they were approved by the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee’s 14 members, one of which is Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., and selected by the Postmaster General.

One stamp depicts a “bang-bang play” at home plate in which a runner slides in and is called “safe” by the umpire whose arms are emphatically outstretched. The other stamp has an image of Andrew “Rube” Foster superimposed over a background that features a ballpark.

Foster, a former player, manager and businessman, is regarded by many as the “father” of the Negro Leagues as he and a group of other black entrepreneurs joined to form the Negro National League, which spawned the formation of rival leagues.

Roy Betts, a USPS spokesman, said that public write-in submissions are typically how stamps are decided each year. He added, from there, they are then sent to the committee, where they are evaluated and measured by set criteria.

“There was a groundswell of support from many different people for the Negro Leagues to be honored,” said Betts. “For years, fans, the museum and politicians have asked for the stamps and now they’re available. If your local post office runs out, you can ask them to re-order more.”

Another tidbit of irony and symbolism wasn’t lost on Betts or the USPS. Betts hinted that having the unveiling a mere hour’s drive from Topeka, Kansas (origin of Brown vs. Board of Education) wasn’t a coincidence. “Everything lined up perfect,” said Betts.