The renewed version of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s campaign to lift poor people is holding its first national mobilization, with actions and events planned Monday in 32 states and the nation’s capital.

Poor people, clergy and activists in the Poor People’s Campaign plan to deliver letters to politicians in state Capitol buildings demanding that leaders confront what they call systemic racism evidenced in voter suppression laws and poverty rates.

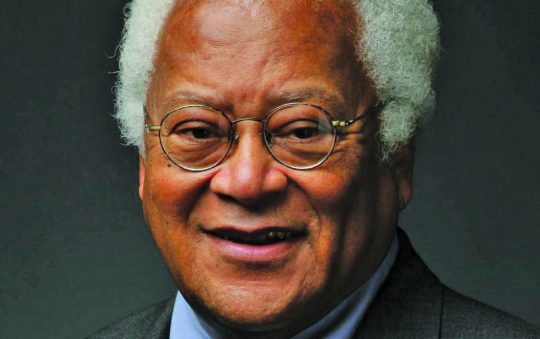

Among those who have signed on to the campaign is the Rev. John Mendez, pastor of Emmanuel Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, who recalled protesting in New York City in the 1960s.

“I’ve been waiting for almost 50 years for this to actually happen,” said Mendez, 68.

The campaign is especially important now because the leaders who don’t want to help the poor “should not have a free hand to say and do whatever they want and there be no resistance,” he said.

Led by the Revs. William Barber of North Carolina and Liz Theoharis of New York, the campaign officially began Dec. 4, 50 years after King started the first Poor People’s Campaign. King was assassinated a few months later and “nobody really picked it up” until now, Mendez said.

The letters to politicians call for a new course in government. “Our faith traditions and state and federal constitutions all testify to the immorality of an economy that leaves out the poor, yet our political discourse consistently ignores the 140 million poor and low-income people in America,” the letter states.

Barber, who will be among the group that delivers letters to the office of House Speaker Paul Ryan and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, said the campaign is building toward a “season of direct action and civil disobedience” that begins on May 13 and continues through June 21, the anniversary of the slayings of three civil rights workers in 1964 in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

The actions, including a poverty tour, will be followed by more work as part of a multiyear campaign to build power “among the poorest and most powerless communities,” he added.

And on Feb. 12 _ the 50th anniversary of the sanitation workers’ strike that brought King to Memphis, where he was assassinated _ fast-food cooks and cashiers plan to walk off their jobs in Memphis to support higher wages and union rights. Protesters plan to march from Clayborn Temple to Memphis City Hall, the same route the sanitation workers took.

The most important part of the campaign is that the people who are hurting because of poverty and racism are its leaders, Theoharis said. “I feel very positive that the real heroes and heroines of our country are coming together to cross all kinds of lines that usually divide us like race, gender, economic status, political party.”

Leslie Boyd of Candler has followed Barber since he began the “Moral Monday” protest movement in North Carolina almost five years ago. Her son, Mike Danforth, was 33 when he died of colon cancer in 2008 because he lacked insurance even though he had a job and couldn’t afford the yearly colonoscopies that he needed.

Her hope for the campaign is that it changes what she sees as a national narrative that not only blames the poor for the poverty but uses religion to do so. Too many people believe that “if you were a good person, Jesus would bless you,” she said.

U.S. Census figures show that the poverty rate among blacks was 22 percent in 2016, while it was almost 9 percent among whites. But in sheer numbers, almost 17.5 million white people are classified as living in poverty, compared to 8.7 million blacks. The U.S. poverty rate was almost 13 percent in 2016.

“It’s not immoral to be poor,” said Boyd, 65. “It’s immoral to make people poor with our actions as a government and as a people.”