Special to the Sentinel

Throughout his childhood, the only awareness Phil Allen, Jr. had of his paternal grandfather, Nathaniel Allen, was his absence. Allen sensed that the man existed, even though his grandmother, Rebecca Allen, did not display photos of her husband, Nate, as he was known in her home. It wasn’t until well into adulthood that Allen, now 47, learned why memories of his grandfather felt burdened by sadness.

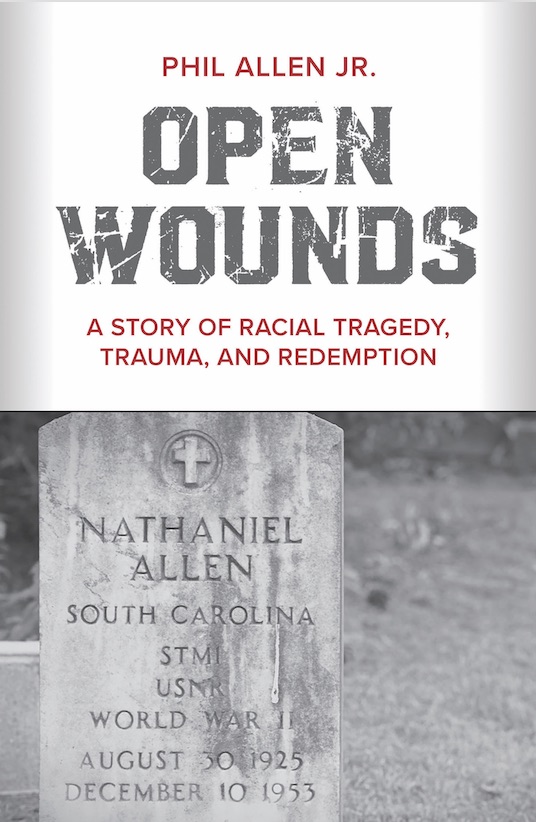

Nate Allen was murdered on the Sampit River in the town of his birth – the low country of Georgetown, South Carolina – in 1953. A Navy veteran, Nate was 28-years-old when he was killed, leaving behind his 24-year-old wife, Rebecca, and four children.

Nate drowned after an accidental fall from his boat into the Sampit, the Allens were told. They learned shortly thereafter, however, that Nate was killed by a bullet to the back of his head, not drowning.

“Jim Crow was a way of life in the South at that time,” said Allen, describing the restrictive state and local laws enforcing racial segregation of Black men and women in the south. “Losing her husband the way she did caused my grandmother to bury her anguish with my grandfather instead of speaking to her pain.”

The overwhelming and unexpressed grief that Allen’s grandmother experienced morphed into trauma that radiated through her to succeeding generations of her family. Allen recalls that his Georgetown childhood offered him and his siblings the joyful and dreadful in equal measure.

Seared into his memory are the violent outbursts from a father who – Allen today understands – was navigating trauma of his own. It fell to Allen’s mother, Vernelle, his grandparents and extended family to provide the loving guidance and steady hand that he and his sisters needed.

“When my grandfather was killed, my father was just two-years-old and he was around the age of nine when he was told the circumstances of Nate’s death,” Allen recalls. “My father is Phil Allen, Sr. and my namesake. He grew up without the male influence he needed in his life and without the experiences that would, in turn, teach him how to be a father.”

Where the younger Allen found and expressed joy was on the basketball court, making a name for himself as a point guard and shooting at Georgetown High School and in college as a student at North Carolina A&T. “Back then, the basketball court was my sacred and safe space,” said Allen in a reflective moment vaguely reminiscent of prayer.

Allen found meaning in another “sacred and safe space” that awaited him when he sought mentorship and community support in 2004 in answering his calling to the ministry. Still, for Allen, there were questions that remained ever-present and persistent, questions about his grandfather’s killing and its impact on his family that refused to linger in the shadows.

Allen was in his mid-thirties when he made his first attempt to query his grandmother about Nate’s death. Her response – “Leave me alone with that” – stern, and final.

“My grandfather’s killing was still too painful for her to talk about,” said Allen, who now lives in Pasadena where he is pursuing a Ph.D. in Christian Ethics at Fuller Theological Seminary.

“I was curious. My question to her manifested a physical response where her body became tight and small. She just shrunk into herself,” he said.

Perhaps she was tired, perhaps Rebecca Allen was simply ready to release a burden to her grandson – he’s unsure which – when he asked again during a 2015 visit to Georgetown. It was then that she spoke to him about the truth of her husband’s death. A year later, Rebecca Allen passed away. She was 86-years-old.

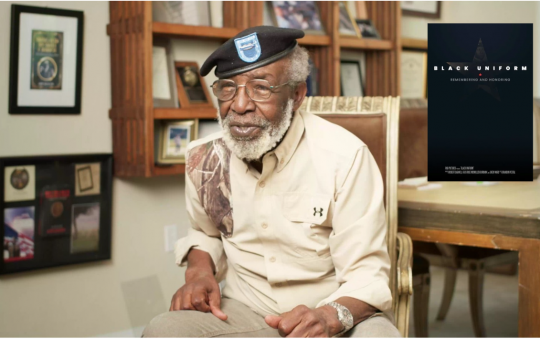

Inspired to share the story of his grandparents, his family and his own, Allen is the author of “Open Wounds: A Story of Racism, Trauma, and Redemption,” released this month by Fortress Press. Allen in 2019 wrote and co-produced the documentary short, Open Wounds, , a visual and emotional telling of his family’s story.

“With the book, the overarching theme is about intergenerational trauma from racial tragedy,” says Allen. “At its core, the book asks how do we deal with this issue of racism in our nation? We need to heal in the Black community, in the white community and learn how we can all heal together as we move forward.”