It’s the year 2020 and we are still fighting systemic racism – not just in our neighborhoods and streets, but also in our healthcare system. The roots run deep –the 19th and 20th centuries included several ground-breaking studies which advanced medicine. However, sadly they relied upon harm to Black patients, experiments without consent, or painful surgeries without anesthesia to name a few. There is a dark and complicated history that created mistrust and barriers between the Black community and medical professionals.

Although U.S. healthcare practices and medical research have improved drastically, there remains significant room for improvement in many areas, including access to healthcare, bias in patient care, and consistently worse patient outcomes for minority populations. The Black and Brown communities continue to be overrepresented where they don’t want to be – a review of the COVID-19 data illustrates that racial health disparities are still significant. So what do we do?

We need more Black medical professionals.

There must be a purposeful and sustained effort to increase diversity amongst medical providers. My presence in hospitals as a Black physician is important for my community. Derek (alias) was described as a difficult patient, a drug seeker, depressed. He was a Black teenager who suffered from Sickle Cell Anemia and was a frequent flyer to the hospital. My colleagues were unable to connect with him and determined that he was uncooperative. But I look different than my colleagues, and my approach and background helped make a connection. I sat and talked with him, sharing that members of my own family are sickle cell carriers. I acknowledged he probably hasn’t seen many Black doctors, and that can feel isolating. His mood brightened up. He revealed his disease had sparked a new interest in medicine. In that moment I was better able to meet a young Black man where he was. A number of studies suggest that patients are generally more comfortable and have better communication and a more positive experience when cared for by doctors they culturally relate with.

While African Americans make up 13% of the U.S. population, Black doctors represent only 5% of U.S. physicians, and only about 8% of U.S. medical school applicants. Ensuring there are more physicians of color will help improve healthcare experiences and outcomes for people of color.

We must educate ourselves on the disparities, bias, and systemic racism that disadvantage ‘under-represented in medicine’ (URM) students. The medical community must be intentional with recognizing and understanding our biases and correcting them in order to purposefully grow the number of U.S. minority doctors.

We must strengthen healthcare career pathways for Black youth.

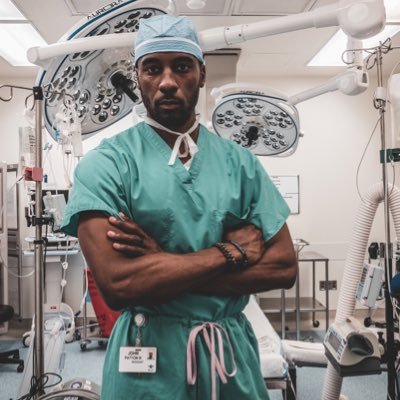

I understand the significance of me (a Black man) as a physician. I also know it’s bigger than me. It’s important for me as an African American anesthesiologist to be visible in my community and in the digital space. From information sharing to simply seeing someone who may look like you, social media offers a powerful tool that can build community among other Black medical professionals, while also showing Black boys and girls they too can become doctors or any other professional.

Unfortunately, access to resources remains a barrier for Black communities, and economic and educational disparities plays a role in this. Redlining and segregation stripped Black communities of resources and in many respects, these inequalities remain today. Young people, particularly people of color, must have educational opportunities that spark an interest in healthcare, regardless of their zip code or how well-funded their local school district is.

We must be creative about the opportunities and resources we are allocating to lower-income and minority neighborhoods. We must give all kids a better chance at manifesting their dreams and meeting the qualifications for medical school. A repeal of California’s Prop 209 to reinstate Affirmative Action policies is a good step, but it’s not a comprehensive solution. We need improvements at inner-city schools, wider availability of quality after-school programs, heightened access to technology and the internet for lower income families, and committed teachers who keep drawing minority students back into the healthcare pipeline when they lose their footing, face barriers, or waver in interest.

Our country’s history of racism and inequities in healthcare continues to permeate throughout our communities, quietly influencing the approach of medical professionals and impacting patient outcomes. It’s time to devote the resources necessary to improve diversity in medicine. A more diverse workforce will improve patient outcomes, help advance medicine, and propel us towards a brighter, more just healthcare system for all.

John W. Patton III, MD, MBA is a Fellow Physician in Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Medicine at the Cedars-Sinai Department of Anesthesiology.