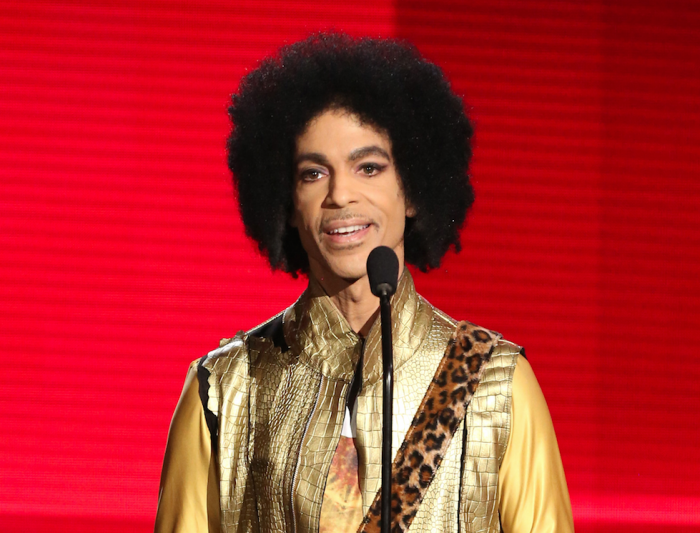

Slight, soft-spoken and just 5-foot-2, Prince improbably cut an imposing figure.

So it was two years ago, when I waited in his Paisley Park studios for what would be our third and final sit down: Me, the commoner, awaiting the prince who was actually king.

The ground rules for the interviews were always intimidating: No cameras, no phones, and absolutely no taping of any sort. He had wanted to prevent me from taking written notes as well, but I balked: How else to keep record of an interview that I thought would run a couple of hours, and actually stretched into the morning hours?

Yet when he walked in the room, wearing a cream-colored flowing outfit and an image of himself on his shirt, what emanated was warmth. Smiles and jokes followed, and Prince revealed a man who was insightful, intelligent, humble, spiritual and even playful _ he played pingpong with his fellow musicians in see-through acrylic heels.

It was a side of Prince he did not share with many: For most, the persona was the mercurial, sullen genius, standing alone, the public at a distance.

Perhaps it was purposeful, to keep the shroud of privacy that eludes most celebrities, to keep a bit of Prince Rogers Nelson separate from the artist formerly and then once again known as Prince.

But in interviews, his layers peeled away, exposing wit and humanity.

The Purple One extended that particular persona to his surroundings _ purple was everywhere, from his dressing room to his Paisley Park studio.

Candles contributed to the peaceful ambience. An attentive host, midway through our marathon interview, he insisted that I must eat, and dispatched an assistant to get me something at a nearby restaurant (though it couldn’t be meat, because Prince was a vegetarian). When I finished, he cleared my plate.

He wanted to share a lot _ up to a point. In our last interview, he took me to one of what were surely several inner-sanctums at Paisley Park, and played me unheard music; he also popped up YouTube to play me some of his inspirations, from Dionne Warwick to James Brown.

At another point, he pulled me aside and asked if I had gotten everything I needed, and proceeded to talk to me about everything from his religion to what he thought of Andre 3000 as Jimi Hendrix. Still later, he called me into a TV room to watch a late-night talk show appearance featuring Anthony Anderson recounting meeting Prince, but when it was over, and I wanted to talk with him about it, he was gone.

It was nearly 2 a.m., and it was clear my time was up.

___

Our first meeting came in 2004: He was celebrating renewed success after his first album in several years, “Musicology.” He greeted me with a smile, and let me into his dressing room but first checked to make sure I was following the rules: “No tape recorder, right?”

Once we sat down, Prince explained that he didn’t want to be taped because he wanted us both to be fully engaged in the interview. At other times in our interviews over the years, he would ask me to stop taking notes, so I could fully absorb all that he had to say.

He talked about his spirituality: After being introduced by musician Larry Graham, he had become a Jehovah’s Witness in the latter years of his life, and the star who used to relish shocking audiences with sexually explicit lyrics took most of those songs off his concert playlist: No cursing was allowed in his presence either. Bible references peppered our conversation: He would point to the scripture to underscore his points (and he knew his verses well).

“What we have today is the same situation right now that Noah faced,” he told me in 2004. “Some rain is going to come, and it’s time to get on the ark. The best thing we can do is to keep our lives in order and our conduct clean.”

He was also socially aware, particularly when it came to matters involving the African-American community. While in his prime he would embrace racial ambiguity and, in interviews, he spoke forcefully about the disenfranchisement of black people; he attributed the uprisings in Ferguson, Missouri, to the lack of ownership and positions of leadership of the black community there; and later, in a quip about the 2014 sci-fi movie “The Giver,” he noted that the future must be all white, because there were no black people in the film.

Perhaps the most forceful moments of our interviews over the years dealt with his fierce belief that artists should maintain control over their own music, and how the music industry exploited recording artists for gain. Prince’s battle with Warner Bros. Records over his own catalog shook the industry, and would change the trajectory of his career: He wrote “slave” on his face, and changed his name to a symbol as he fought their grasp. He started his own label, NPG Records, and sold music to the fans direct through the internet, though he would later become disenchanted with that model because of rampant piracy, and routinely took his music off of YouTube and streaming services like Spotify.

In our last interview, he had finally taken control of his music back, winning the rights to his master recordings. While he still dealt with labels for distribution, he continued to sound the alarm on the inequities in the music business: “The Bible says you’re not supposed to sign your inheritance away.”

He had hoped to convince others in the music industry to leave major labels and strike out on their own, and he saw his own label as a conduit. He talked about having a collective, and empowering other artists. Finally, he was in the position of power when it came to his own music, past and present, and he was liberated by it, and it gave him new passion.

He had recorded two new albums in 2014, one solo record, “Art Official Age,” along with music from his latest protege act, 3RDEYEGIRL, “PLECTRUMELECTRUM.” For the first time, he allowed someone else to produce his music: upcoming musician Joshua Welton. And he boasted that the crop of musicians he was working with was among the best he’d ever experienced.

“It sounds like freedom, and there is a joy to it now,” he said of his music-making process.

In many ways, Prince seemed to be on a victory lap in recent months: He was doing more performances, and had signed on to write his memoirs. During one of his last performances in New York, where, as was typical, he performed two sets, he spoke eagerly of putting his memories down to paper.

We’ll likely never get a chance to relish in the memories that he was willing to share with us. But we can hold on dearly to the magic of the nearly four decades Prince reigned.