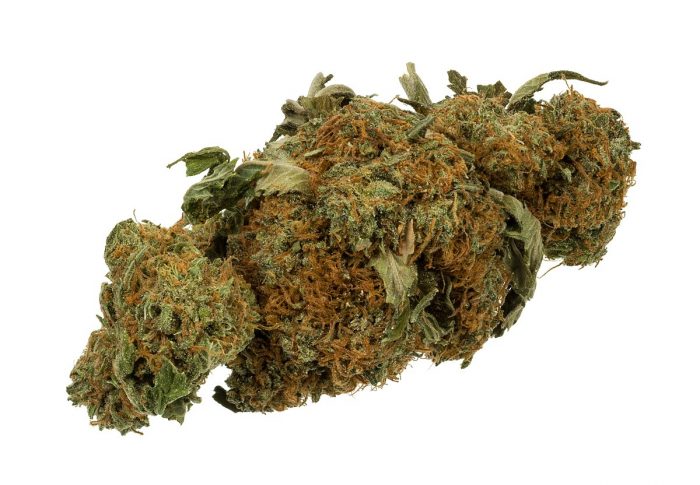

A City Council committee exploring a proposal to make Los Angeles the first city in the nation with its own bank was told last week by legal experts that accepting deposits from cannabis businesses could cause serious problems.

Council President Herb Wesson proposed the creation of a public Bank of Los Angeles during a speech in July while calling on his fellow council members to help devise a legal cannabis industry in the city that works.

But lawyers with the City Attorney’s Office told the Ad Hoc on Comprehensive Job Creation Plan Committee that the public bank would be subjected to the same laws that any other bank is when it comes to marijuana businesses.

“As a city, we might run into problems if we were to accept deposits from the cannabis industry,” Deputy City Attorney Gretchen Smith said.

Because marijuana is still a Schedule 1 drug at the federal level, accepting deposits from cannabis businesses could violate the Banking Secrecy Act and open the city and employees at the bank to potential liability, she said.

The Los Angeles City Council recently approved final guidelines for the cannabis industry that will become active when marijuana becomes legal for recreational use in the state of California on Jan. 1.

The city has estimated it could collect up to $100 million in new taxes from the industry, but legal operators in the city will run into the same banking issues that operators across the nation are encountering because most banks don’t want to do business with them.

Smith also told the council that two memos were issued by the Obama administration that created guidelines for banks to accept deposits from marijuana businesses, but they are “onerous” because it is a extensive process with so much paperwork that most banks don’t want to do it because of the “cost-benefit analysis.”

Smith also said the Obama memos were just guidelines, not statutory, and could easily be rescinded by the Trump administration or any future administration. She also said that if they were rescinded, “there is no way to do banking business with cannabis businesses.”

The committee was also told by Assistant City Attorney Noreen Vincent that the office had not yet discovered any laws that would prohibit the city from opening a bank. State law would prohibit the state or counties from “loaning out their credit,” she said, but there are no restrictions on cities that the office has yet found.

The committee directed the City Attorney’s Office and some other departments to report back on a number of issues, including a full legal analysis of the Obama memos and a report on efforts in the state by other cities to open a public bank.

In the directions to city staff, Wesson said he wanted to stress “the thought behind this — is this feasible to create a municipal bank? I just want to go into this one more time. It is not creating a bank so that it can bank cannabis. That is something that kind of came along after. So when you are doing your research, you shouldn’t say, `Oh, they shouldn’t do this because of cannabis.”‘

The comments indicated that Wesson may be giving up hope that the bank could be a main depository for the cannabis industry.

During Wesson’s speech in July, he cited one of the benefits of a public bank being that the cannabis industry could use it, but also pointed to other benefits, including that it could be used to finance local entrepreneurs and affordable housing.

“We cannot bury our heads in the sand on the issue of recreational and medical cannabis legalization. Instead we must strive to reasonably regulate the emerging industry while creating opportunities for Angelenos,” Wesson said in July.

No city in America has its own bank, and the only public bank in the nation is the Bank of North Dakota, which was created in 1919.

The motion Wesson introduced calling on the city to explore creating its own bank said the Bank of North Dakota is a successful model on how cities and states could use their banking needs to give back to the community.

Although it was not mentioned in Wesson’s motion, the new bank could also help the city avoid entanglements with major financial institutions with which it is increasingly wary of doing business.

The city settled a lawsuit with Wells Fargo last year after some of the bank’s employees created more than 3.4 million unauthorized accounts as a way to meet aggressive sales goals set by management. The bank paid $50 million in civil penalties to the city of Los Angeles and $135 million to two federal agencies, and was ordered to provide restitution to affected customers.

The city does the majority of its banking with Wells Fargo through roughly 800 accounts. But the full City Council, just prior to the committee meeting, approved more stringent rules for banks that want to do business with the city that could end up leading the city to divest its funds from Wells Fargo.