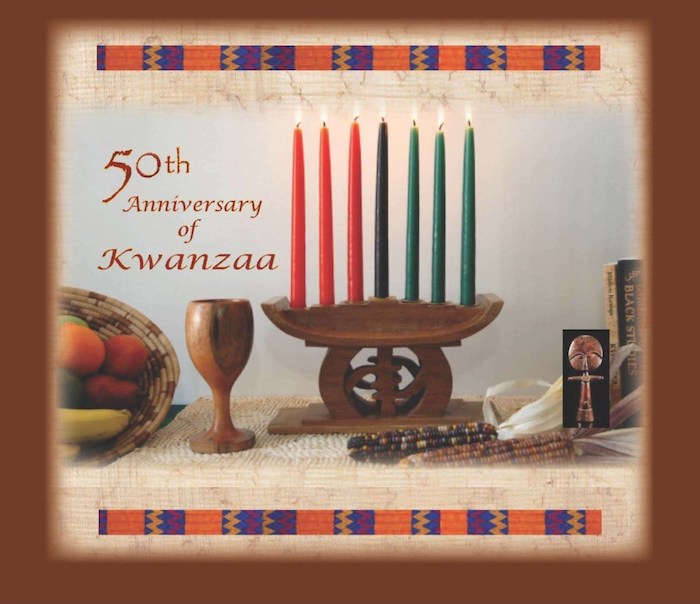

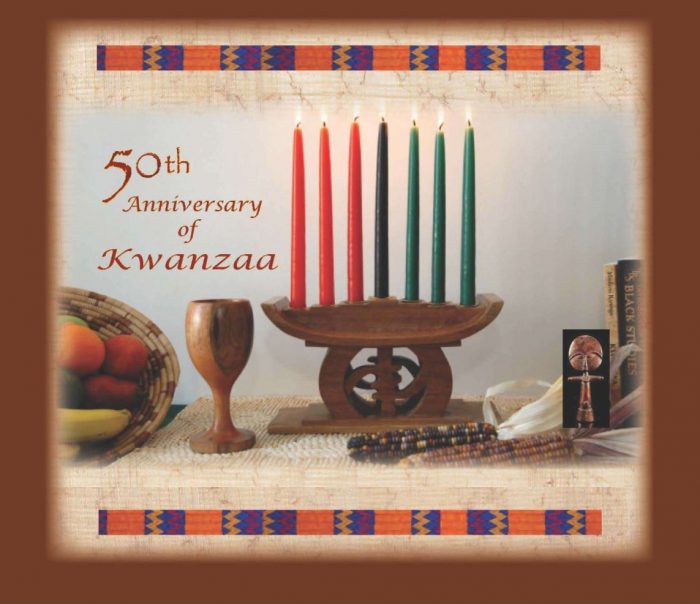

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the pan-African holiday Kwanzaa, observed by millions of Africans on every continent in the world and throughout the global African community from December 26 to January 1. Created in 1966 by Dr. Maulana Karenga, then a former doctoral student at UCLA and chair of the organization Us, which he still leads, it is a celebration of family, community and culture. To mark this occasion and give our readers a fuller understanding of this international holiday, founded here in Los Angeles, we sat down with Dr. Karenga to interview him on his thoughts about Kwanzaa’s origins, practices, principles, meaning and future.

LAS: Dr. Karenga, what are some of your first thoughts about reaching this 50-year milestone in the history of Kwanzaa? Did you imagine it would have grown this large and lasted this long?

DMK: First of all, I’m grateful to see my work flourish in my lifetime. Many of the great people in our history were not able to see how much their work, suffering and sacrifices enriched our lives and pushed our struggle forward. But I’ve been blessed to see my work begin in a family home, spread around the world and be embraced by millions of African people throughout the world African community.

Secondly, as far as imagining how things might develop, I always note that I’m no prophet and therefore could not reasonably predict the future. But I believed that if I could create something of beauty and value and offer it to our people, our people would embrace it and use it as I had wanted them to do, that is to say, to celebrate themselves and to use The Seven Principles, the Nguzo Saba, as a Black value system, an African value system, to anchor, orient and direct their lives toward good and expansive ends. Having said this, however, I’m still very impressed and pleased with the rate and extent of Kwanzaa’s growth among our people all over the world.

LAS: We know that people have asked you this numerous times, but still I’m sure it is of interest to our readers. Why did you create Kwanzaa and what were the conditions in which you created it?

DMK: I understand; it’s a standard but important question. For the discussion of context and purpose of our actions is always important. During the period of my focused research, study and creating of Kwanzaa, the Black Freedom Movement was a dominant activity and focus for Black people. 1965 represented the beginning of the Black Power period of the Black Liberation Movement and I had left my doctoral studies at UCLA to join the Movement. It is during this period that I began to build my organization Us, which means Us Black people, and further developed my philosophy, Kawaida, out of which I created both Kwanzaa and the Nguzo Saba.

LAS: Did you create Kwanzaa and the Nguzo Saba at the same time?

DMK: No, I created the Nguzo Saba first and then Kwanzaa as a means to introduce and promote the Nguzo Saba and related communitarian African values, values that stress the community and collective.

So I created my organization Us, my philosophy Kawaida, the Nguzo Saba and Kwanzaa in the context of the Black Liberation Movement. As a student activist, I wanted to make use of my knowledge as Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune and Dr. W.E.B. DuBois had urged, in the service of our people. And this meant for many of us using our knowledge in the service of the Movement to advance the liberation struggle of the people.

Therefore, I created Kwanzaa in this context for three basic reasons. First, it was to reaffirm our rootedness in African culture because we had been lifted out of our own culture and made a footnote and forgotten casualty in Europe’s culture and history. Thus, our struggle was to return to our own culture and history, speak our own special cultural truth and make our own unique contribution to how this society was reconceived and reconstructed. Second, I created Kwanzaa in order to give us a time when we as African people all over the world could come together, celebrate ourselves, reinforce the bonds between us, and meditate on the awesome meaning of being African in the world. And now more than any other time during the year, millions of Africans come together throughout the global community to do just this. We get e-mails and photos and youtube presentations from Africa, Asia, Latin America, Europe and the islands of the seas describing and showing Africans celebrating Kwanzaa. Third, I created Kwanzaa to introduce and reaffirm the importance of communitarian African values, values that stress and strengthen family, community and culture. And of course, the hub and hinge on which the holiday turns are the communitarian values we call the Nguzo Saba, The Seven Principles, which are in Swahili and English: Unity (Unity); Kujichagulia (Self-Determination); Ujima (Cooperative Economics; Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics); Nia (Purpose); Kuumba (Creativity); and Imani (Faith).

LAS: Although, we don’t hear much about it recently, once there was a concern among some Christians that Kwanzaa was a threat or challenge to Christmas. Could you tell us what their concerns were and how you answered them?

DMK: First of all, we explain that Kwanzaa is a cultural holiday not a religious one and that what we are celebrating is our people and their culture and history and that African culture is broad enough and deep enough to involve all faiths. In fact, we also pointed out that perhaps the greatest number of celebrants of Kwanzaa are Christians, but that African people of all faiths celebrate Kwanzaa—Christians, Muslims, Black Jews, Buddhists, Bahai, Maatians, Ifans and other adherents of historic African religions. There is, however, an ethical dimension to Kwanzaa which also offers common ground regardless of our faith. For example, all of our faiths teach us to speak truth, to do justice, to care for the poor and vulnerable, to have a rightful relationship with the environment, to constantly resist evil and injustice, and always raise up and pursue the good. And Kwanzaa stresses these values among others. But again, this is common ground, not ground for division.

LAS: How did you go about conceiving the holiday? We usually think of holidays as something people did a long time ago, but to have someone in our midst that created a global holiday is something rare. So, certainly, our readers will want to know what were your motivations and what were you thinking at the time?

DMK: As I said, I was interested in creating something of value to aid in the life and struggle of our people. I wanted it to be an institution that lasted, that took roots in the community and became permanent because it continued to serve the interest of the people. I chose a holiday as this instrument of instruction and struggle because it involved also my concept of the need for a cultural revolution. And by that I meant a radical rethinking about who we are as an African people and about the need for revolutionary change in this country. We argued that the key crisis and challenge in Black life is the cultural crisis and challenge. And that until we break the monopoly that the oppressor has on so many of our minds, liberation is not only impossible, it’s inconceivable. So there was a thrust to raise the consciousness of the people and we argued that in order to free ourselves we must be ourselves, Africans, a people oppressed and in struggle. And we must be self-conscious about this. So Kwanzaa became a way to focus on being African in the world, an expansive way, not just in terms of the arts, like music and dance, but especially in value orientation and worldview, how we understood the world and ourselves in the world and what we saw as our fundamental ethical obligation to transform ourselves and the world. So Kwanzaa includes all those kinds of discussions, although many times the media and many celebrants don’t go that deep. But if they read my standard book, Kwanzaa, A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture or my new text, The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good in the World, they will find these ideas elaborated on extensively.

LAS: When you created Kwanzaa, did you create it to fulfill a need in Black people?

DMK: I created Kwanzaa for positive reasons and I think it’s important for us not to pose Kwanzaa as a kind of problem-solver for Black people because often when the media asks questions like that, they are trying to approach the holiday and the people from their conception of pathology. I created Kwanzaa to build on the best of African thought and practice using models of excellence and achievement from our culture, ancient and modern, Continental and Diasporan. It was not done to correct a problem, but to aid us in our struggle for liberation and to enhance our capacity to build good, meaningful and expansive lives, and advance the struggle of our people. Again, it was a positive thrust not a cure or problem-solving initiative. Indeed, it was an act of freedom, breaking away from the teachings and practices of the dominant society, recovering hidden and erased history and culture, returning to the best of our values, and resisting Eurocentric impositions on our lives.

LAS: What is your vision for Kwanzaa and its celebrants in the future? How do you see the holiday developing and continuing to have meaning for African people all over the globe?

DMK: The enduring beauty and meaning of Kwanzaa will always rest in the hearts, minds and practice of African people who use it to anchor and enrich their lives and celebrate it as a celebration of their unique and equally valid and valuable way of being human in the world. Clearly, their practice of the Nguzo Saba, The Seven Principles, and their holding fast to the cultural grounding and orientation which they provide will enhance the holiday’s capacity to endure and flourish. I am very optimistic about the future of Kwanzaa because African people have found in it something of enduring beauty and value and I believe that they will continue to hold this to be true and to add their own beauty and value to it in a practice of self-conscious self-determination in the most culturally grounded and expansive ways.

LAS: Dr. Karenga, given that this is the 50th anniversary of Kwanzaa, what are the special activities to mark it?

DMK: As usual, on the first night of Kwanzaa, December 26, which is called Umoja Night, we will have the gathering of the community and a candle lighting ceremony to open the week of celebration of Kwanzaa. Leaders and other persons of the community will participate in a collective candle lighting ceremony called “Lifting Up the Light That Lasts” which refers to lifting up enduring moral principles, especially the Nguzo Saba, The Seven Principles and making a wish for the community in terms of each principle. This will be held at the headquarters of Kwanzaa, the African American Cultural Center (Us), 3018 West 48th Street, Los Angeles, at 6:30pm.

And on December 31st, we always have an African Karamu or feast with African foods, music, dance, poetry, narratives, etc. in celebration before January1st which is called the Day of Meditation. For those interested in tickets to the Karamu, they may call the African American Cultural Center at (323) 299-6124.

In addition, we have a city-wide Kwanzaa Ujima Collective which plans events for each day of Kwanzaa and they will issue as usual a calendar outlining those events. Finally, Tiamoyo and I always travel back East to share Kwanzaa celebrations with others in various cities, always returning for the Karamu.

Let me close by saying Heri za Kwanzaa / Happy Kwanzaa to everyone and with the Kwanzaa wish for all: May you be given all the heaven grants, the earth produces and the waters bring forth from their depths.