Whether we discuss emancipation in June, independence in July, revolt and revolution in August, Kwanzaa and cultural and political liberation in December, or achievements against the odds, resilience and resistance in February, the issue, imperative and urgency of freedom and struggle are always with us. Indeed, it runs like a red line through our most ancient, awesome and humanity-revealing history.

It is a central concern in the ancient ethical teachings of our honored ancestors in the Sacred Husia in the Four Good Deeds of Ra which foreground and emphasize that humans are divinely endowed with certain capacities, conditions and associated rights related to and reflective of freedom.

And it is found in the continuing courageous questioning of and critical judgment on American society by our people and in their ongoing striving and struggle to achieve and constantly expand an inclusive realm and reality of freedom, justice and other shared good.

Thus, every Fourth of July we are morally compelled to stand again with Nana Frederick Douglass when he gives his classic speech on the meaning of July 4th for Black people in this country at Rochester, New York in 1852. And we do this first because of the pressing immediacy and compelling urgency of the issues involved: issues of freedom and unfreedom; justice and injustice; inclusion and exclusion; the affirmation of human rights and their denial; and the severe and sustained suffering that the lack of freedom and justice imposes on us and the oppressed peoples of the world, and indeed, the world itself.

The immediacy and urgency of these issues is clear given our conversations and struggles around reparations, the abolition of prisons, the end of systemic and police violence, the simple and clear right of freedom of expression at the ballot box, the right to be free from the Europeanization and destruction of our neighborhoods and communities under the euphemism of gentrification, the rights to clean water and food security, and the rights to guaranteed income for a life of dignity and decency and a quality education, as Nana W.E.B. DuBois says, “not only to make a living but also to make a life.”

Also, we must stand with Nana Douglass at Rochester to practice the morality of remembrance and honor the reciprocal obligation to represent him and our people and their right to freedom as he represented us during the most brutal and savage of circumstances of unfreedom and oppression, the Holocaust of enslavement. He advises us at Rochester that to forget our people in oppression or minimize their suffering can only inspire the contempt and condemnation from both God and the world.

Indeed, he says, “To forget them, to pass lightly over their wrongs, and to chime in with the popular theme, would be treason most scandalous and shocking, and would make me a reproach before God and the world.”

Thirdly, to stand with Nana Douglass at Rochester means to recommit ourselves to the unavoidable radical transformative struggle for real, deep-rooted and inclusive freedom in this country and ultimately the world. Nana Douglass taught us that in the midst of oppression, there is always those who would counsel caution, compromise, accommodation and even surrender.

But as he says, “With brave men (and women), there is always a remedy for oppression.”

And that remedy is always unavoidable, righteous and relentless struggle. As we say in Kawaida, in the midst of oppression, there’s no reliable remedy except resistance, no strategy worthy of its name that does not privilege and promote struggle, and no way forward to freedom except across the battlefield for a new world.

Nana Douglass tells us that we are compelled to stand strong and unwavering on the platform and battlefield of freedom, not compromised by accepting false claims of inclusive freedom, or the bad-faith fanfare of the freedom offered to all except to different others by the founding fathers. Indeed, he says, in the name of the oppressed “Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.”

This is the falseness, false claims and bad faith that have followed us since the founding of the country with its racist, class and gender conceptions of freedom, justice and human rights and which we from the beginning resisted.

And we must righteously and relentlessly resist their determined descendants, the callers of consent and compromise in the face of injustice and unfreedom, the suppressors of dissent and resistance, the outlawers of learning and what Nana Douglass calls “the lovers of ease and the worshipers of property.”

He tells us that it is “exceedingly easy” to agree to the obvious and non-controversial and to side with the superficial, popular and fashionable. But he continues, “To side with the right, against the wrong, with the weak against the strong, and with the oppressed against the oppressor! here lies the merit, and the one which, of all others, seems unfashionable in our day.”

Also, Nana Douglass tells us that in our success in the country and shift in class position, we must not erase or conceal ourselves as Black people and therefore, lose our communal and ethical relationship with our people. Indeed, he stresses on the platform of freedom in Rochester that the ground on which he stands is with his people in their liberation struggle.

He recognizes “the distance between this platform and the slave plantation, from which (he) escaped,” the distinction between the enslaved and the enslaver and he self-consciously affirms that he speaks “from the (enslaved) point of view, standing, there, identified” with them, making their oppression his own. Here he embraces the position, as Nana Harriet Tubman and all our freedom fighters, great and every-day, that freedom is indivisible and that unless we are all free there is no freedom, salvation, sanctuary or safety for any one of us.

Continuing his courageous questioning of America and his exposing and opposing the oppressive nature of American society, like Nana Fannie Lou Hamer, he urges us to question and criticize America in its wrongfulness and oppression, it’s inhuman logic and life-destructive ways. He asks the question, “Is it to be settled by the rules of logic and argumentation, as a matter beset with great difficulty, involving a doubtful application of the principle of justice, hard to be understood?”

Moreover, he asks, “How should I look today, in the presence of Americans, dividing, and subdividing a discourse, to show that men have a natural right to freedom? speaking of it relatively, and positively, negatively, and affirmatively.”

He reasons that, “To do so, would be to make myself ridiculous, and to offer an insult to your understanding.” Thus, reaffirming the unavoidable necessity of struggle, he concludes, “It is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake.”

And in honoring this our awesome tradition of righteous and relentless struggle, we must continue the struggle and embody, become and be, the storm, the whirlwind and the earthquake in the interest of African and human good and the well-being of the world.

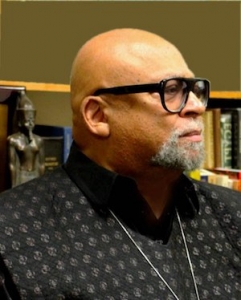

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.