On Saturday, February 2, 2019, Frank C. Braxton Jr., widely regarded as the first Black animator in Hollywood, was posthumously awarded with the Winsor McCay Award at the 46th Annual ASIFA-Hollywood Annie Awards at UCLA’s Royce Hall. ASIFA (the International Animated Film Association) bestows the award, “in recognition of lifetime or career contributions to the art of animation in producing, directing, animating, design, writing, voice acting, sound and sound effects, technical work, music, professional teaching, or for other endeavors which exhibit outstanding contributions to excellence in animation,” per ASIFA-Hollywood’s website.

LA native Frank C. Braxton, Jr. (bd. March 31, 1929) developed a love for drawing as a young boy and was known to carry his sketch book around, capturing images of L.A. in the 1930s and 40s. As a teenager, Frank developed a love for drawing caricatures of his friends and family, and as a senior at Manual Arts High School he filled the 1947 yearbook with his drawings depicting school life.

While studying art and music at LA City College and driving a cab at night, Frank met voice teacher Lee Wintner who introduced him to Ben Washam, a highly respected Warner Bros. senior animator who was taking voice lessons from Witner at the time.

Upon meeting Frank, Washam saw that he had the talent to become an animator. Knowing there were no Black animators, Washam shrewdly approached Warner Studio head Eddie Selzer and asked, “Is it true that Warner Bros. has a policy against hiring of Negroes?” Offended, Selzer emphatically replied, “That’s absolutely not true!”

“Good,” replied Washam, “because I’ve got a Black artist we should hire!”

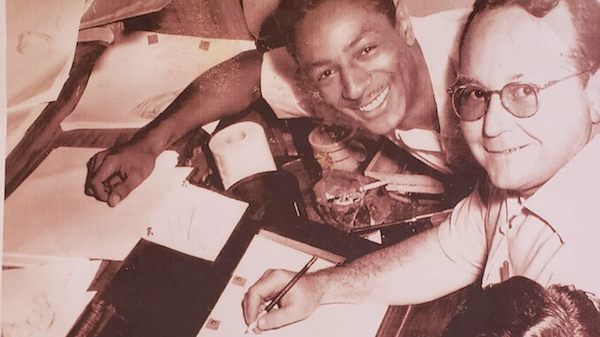

After waiting several months for Warner Bros.’ final decision, the animation industry had its first Black artist. Frank began as an “inbetweener” in the Chuck Jones unit of the mid 1950s. Ben Washam became his mentor and trusted friend for the remainder of his life.

When Warner Bros. shut down for six months to retool, Frank was recommended to Disney Studios where he worked for only 10 days before he was hired as an assistant animator by veteran animator/director Abe Levitow, and then with animator Bill Hurtz at Shamus Culhane Productions, and later at Jay Ward Productions. Hurtz would later recall in Frank’s eulogy that he realized the intense pressures Frank was under as the first Black animator.

Throughout the remainder of the 1950’s and into the early 1960’s Frank contributed to the productions of several shows, including “The Bullwinkle Show,” “Mr. Magoo,” “Alvin and the Chipmunk,” “Beany and Cecil,” and “Linus the Lionhearted,” as well as some commercials and independent projects. During this time, Frank also served as president of the Los Angeles local of the Screen Cartoonists Guild, making him one of the first – if not the first – Black person to be elected president of any film union in Hollywood.

In 1964, Frank seized the opportunity to work in Spain, where at Estudios Moros, he worked as both animator and director in Madrid, then Barcelona. While in Europe, Frank officially represented ASIFA Hollywood.

Frank returned to the U.S. in late 1965, feeling “free and energized” from having worked in environments absent of prejudice. As a free-lancer during this period, Frank spent the majority of his time with Jay Ward Productions, animating and also directing segments of “Rocky and Bullwinkle” and “George of the Jungle,” as well as “Capt’n Crunch” and “Quisp and Quake” commercials.

Other projects included: MGM’s, “The Phantom Tollbooth,” under Levitow, and director John Hubley’s “Urbanissimo,” in 1967. Frank also began teaching animation to inner city youth at the Performing Arts Center of Los Angeles using equipment donated from various studios.

In 1968, Frank began an association with Bill Melendez Productions, on TV specials, “You’re in Love, Charlie Brown” and “He’s Your Dog, Charlie Brown,” and what turned out to be his last project, the feature length “A Boy Named Charlie Brown,” released in 1969, after his death.

Frank Braxton passed away at UCLA Medical Center on June 1, 1969 from Hodgekins Disease. Thankfully, after Frank, many talented Black artists, including Floyd Norman, Leo Sullivan, Richard Allen, Norm Edelen and Ron Husband followed with impressive careers in the industry.

“He was our Jackie Robinson,” said Disney animation artist, Norman.

The award was accepted by his wife, Bette and his two children, Aleta and Scott. Also present at the ceremony were his four grandchildren Alan, Daniel, Kathrine, Michael and nephew Greg.