He will live forever in history as the icon of America’s Civil Rights Movement, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize and “drum major for justice”. January 21 marks the (?) annual day of celebration, honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. here in the U.S. And, while schools will be closed, and some may get a three day weekend, while others may take advantage of sales, it is important to remember why we celebrate.

Had he not been cut down at the young age of 39, King Jr. January 15 would have marked his 90th birthday. Perhaps he would have been proud to see some of the changes that have been made since his fighting-for-justice days. Perhaps he would have also disappointed at America’s setbacks since those days.

While there have been real strides toward equal employment and education, inequality and injustice still remain at the forefront of Black politics. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Blacks are still unemployed at nearly twice the rate as whites, and Blacks are more than twice as likely to live in poverty. And, disparities in education continue to show up in test scores, dropout rates and enrollment in higher education.

King saw the importance of addressing these disparities at an early age.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was born January 15, 1929, the second of three children, in Atlanta, Georgia. Growing up in the south presented plenty of opportunities for the young King to notice that America was troubled. As a young boy, he felt resentment against Whites due to the “racial humiliation” that he, his family, and his neighbors often had to endure in his segregated hometown and all over the south.

King attended Booker T. Washington High School in Atlanta, where he became known for his oratorical skills and was part of the school’s debate team. During his junior year, he won first prize in an oratorical contest sponsored by the Negro Elks Club in Dublin, Georgia. On the ride home to Atlanta by bus, he and his teacher were ordered by the driver to stand so that white passengers could sit down.

King attributed the incident as “one of the angriest times” in his young life. He was exceptional, skipping both the 9th and 12th grades of high school . He attended Morehouse College in Georgia and decided to join the Baptist ministry at age 18. At age 19, he enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with a B.Div. degree in 1951.

King Jr .received his Ph.D. degree on June 5, 1955 from Boston University. That year, Blacks in the south had begun to become tired and restless over Jim Crow, a set of laws that systematically kept them oppressed. In March, Claudette Colvin—a fifteen-year-old Black school girl in Montgomery, Alabama—refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in violation of Jim Crow. At the time, King was on the committee from the Birmingham African-American community that looked into the case. In December, a similar incident occurred when Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus.

The two incidents led to the Montgomery bus boycott, which lasted for 385 days. The situation brought violence to the south’s Black communities but ultimately ended racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses and propelling King into the national spotlight.

As cofounder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference King and his group staged a myriad of non violent protests during which there were often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent.

He had hoped television coverage of the violence against a non violent, unarmed people would bring national attention to the situation, an initiate change. The movement garnered success, however backlashes came in the form of more militant groups urging African Americans to fight back against their oppressors, even if they had to use violence.

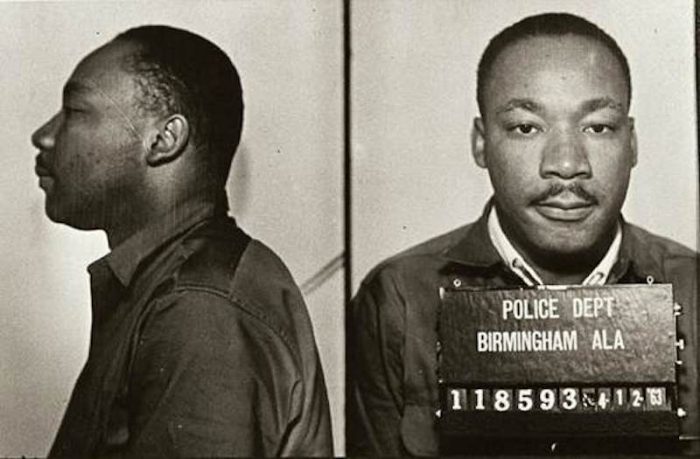

In April 1963, the SCLC began a campaign against racial segregation and economic injustice in Birmingham, Alabama. During the protests, the Birmingham Police Department, led by Eugene “Bull” Connor, used high-pressure water jets and police dogs against protesters, including children. Footage of the police response was broadcast on national television news and dominated the nation’s attention, shocking many White Americans and consolidating Black Americans behind the movement

King was arrested and jailed early in the campaign, from his cell penning the famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”.

“We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed,” he wrote.

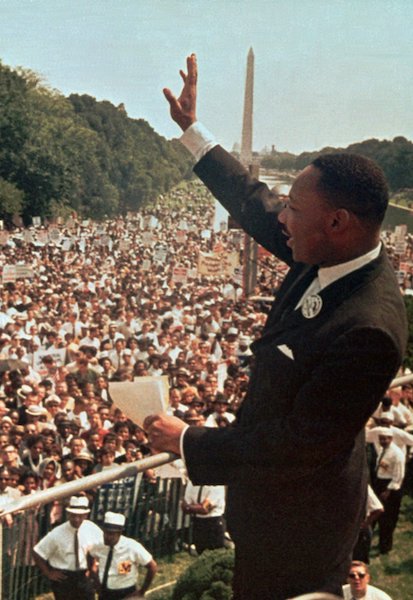

In August that same year, King joined other Civil Rights leaders in organizing the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The march originally was conceived as an event to dramatize the desperate condition of blacks in the southern U.S. and an opportunity to place organizers’ concerns and grievances squarely before the seat of power in the nation’s capital. Organizers intended to denounce the federal government for its failure to safeguard the civil rights and physical safety of civil rights workers and Blacks. But pressure from the government served to dissipate some of the passion behind the march. Some civil rights activists felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the “Farce on Washington”, and the Nation of Islam forbade its members from attending the march.

Nonetheless, the march enjoyed major success and was the venue for perhaps one King’s most famous speeches of all, “I Have a Dream”, a 17 minute presentation about the urgency of equality and justice for America’s oppressed.

King maintained his stance on non violent protests throughout his career, often spearheading events that brought violence against him and his followers. On what is now known as a “Bloody Sunday” in December 1964, King and the SCLC joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Selma, Alabama, where the SNCC had been working on voter registration for several months. A local judge issued an injunction that barred any gathering of three or more people affiliated with the SNCC, SCLC, DCVL, or any of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil rights activity until King defied it by speaking at Brown Chapel on January 2, 1965. During the 1965 march to Montgomery, Alabama, violence by state police and others against the peaceful marchers resulted in much publicity, which made Alabama’s racism visible nationwide.

On March 29, 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee, in support of the Black sanitary public works employees, who were represented by AFSCME Local 1733. The workers had been on strike since March 12 for higher wages and better treatment.

King was booked in Room 306 at the Lorraine Motel (owned by Walter Bailey) in Memphis.

On April 4, 1968, as he stood on the motel’s second-floor balcony, an assasin’ bullet entered through his right cheek, smashing his jaw, then traveled down his spinal cord before lodging in his shoulder. After emergency chest surgery, King died at St. Joseph’s Hospital at 7:05 p.m. According to biographer Taylor Branch, King’s autopsy revealed that though only 39 years old, he “had the heart of a 60 year old”, which Branch attributed to the stress of 13 years in the civil rights movement.

He left in his wake wife, Coretta Scott King and four children, Yolanda, Martin Luther King III, Dexter and Bernice.