Southern football was reserved for white players only, but when USC’s Sam Cunningham ran over, and right by them, Southern whites knew that they needed black athletes to compete.

By Jason Lewis

Sentinel Sports Editor

jasonl@lasentinel.net

“Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever!” –George Wallace, Alabama Governor-1963

The Southeastern Conference (SEC) has dominated college football since the inception of the Bowl Championship Series (BCS) in 1998. Their dominance was most prominently displayed earlier this year when two of its teams, Alabama and LSU, played for the championship.

Looking at the players on the field, a viewer could think that it was the Bayou Classic, played between black colleges Grambling State and Southern.

Just about everybody on the defensive side of the football on both teams are black, and most of the offensive players are as well. But these black athletes are not playing at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU), they are playing for programs that are intertwined with the regions that their universities are in.

Less than 50 years ago none of these players would have been allowed to play for either of these football teams, and black fans were not even allowed in the stadium to watch the games. Blocks away from the stadium that Alabama played in was the church that was bombed, killing four little black girls, and also in that area Bull Conner ordered attacks on black protesters with water hoses and police dogs.

During the era of segregation, college football in the South mirrored society, as blacks were unable to eat at the same restaurants as whites, they were unable to drink from the same water fountains, they were unable to obtain good education or jobs, and they were unable to play college football in the SEC, Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), or the Southwest Conference (SWC- an all-Texas conference which has disbanded.)

College football had a deep tradition in the culture of the South, which was a culture that did not include blacks. The South was dominated by whites who had not gotten away from their past, which included the institution of slavery.

White Southerners wanted to keep their schools separate from blacks, and they wanted to keep their college football the same way.

In 1954, the Brown vs. The Board of Education declared that state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students were unconstitutional, which overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which allowed state-sponsored segregation, as long as the separate facilities for separate races were equal.

The fight to integrate schools had begun, but that fight did not extend to the football field. The Civil Rights Movement had their sights set on the state of Alabama, but Alabama was not ready to allow blacks any sense of equality.

In 1959 Alabama played in the Liberty Bowl against Penn State. Members of their Board of Trustees threatened to boycott the game because Penn State was an integrated school, and they used black players on the football team.

During those times the only thing nationally relevant in Alabama was their football team, and that team was a form of racial pride. The fight to keep the schools segregated was also a fight to keep the football team segregated.

In the North and West, college football had been integrated years before, with the first black player at USC in the 1920s. In the 1939 UCLA had an all-black backfield, which featured Kenny Washington, Jackie Robinson, Woody Strode, and Ray Bartlett. But in the South, even though they had a great talent pool of black athletes to select from, they chose to continue with segregation. Black athletes had to leave home and travel to the North or West to have an opportunity to play and further their education.

That approach hurt Southern schools, as they watched black athletes excel at schools outside of the region. Sports is about winning, so it was only a matter of time before some school brought on a black player.

That school was Maryland, who recruited Darrell Hill in 1963. Hill said that he did not want to be like Jackie Robinson, he just wanted to play football, but he endured the same treatment that Robinson did. He was subjected to racial slurs and taunts, spit on, and physically abused by not only his opponents, but his teammates as well.

Signing Hill made waves in the ACC, as there were bylaws and agreements between schools not to use black players. South Carolina and Clemson threatened to leave the conference because Maryland had a black player.

When Maryland traveled to Clemson for a game, Hill received death threats and he was concerned that there would be a sniper in the stands. In the stadium he heard chants of “Kill the nigger” from the 50,000 white fans in attendance.

Blacks were not allowed in the stadium, so they had to watch the games from outside of the venue on a dirt hill that was called “Nigger Hill.” Hill had a great game in his debut for Maryland, and the black fans on the dirt hill cheered loudly after every big play that he made.

Hill opened the floodgates, as a number of Southern schools started to sign black players. But all of those schools were in the ACC. By 1966, half of their teams had black players, but there were still no blacks in the SEC and SWC. Half of the schools in the SEC had been integrated by that point, but the football teams were still all white.

The SWC followed the ACC’s lead when Baylor and SMU started to sign black players, but the SEC was still holding on to their white traditions.

In 1967, five black students walked on to Alabama’s football team, but none of them made it. Head coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, who had coached black players while coaching at Maryland, indicated that he wanted to recruit black players, but the administrators and the fan base would not have any part of it.

That all changed in 1970. Alabama was unable to play a number of teams from the North because many of those schools did not want to play a team that was still entrenched in segregation. So Bryant looked out west, and USC agreed to travel into the Deep South for a match up of two of the best programs in the nation.

When game day arrived the black population in Tuscaloosa was rooting for the road team. They wanted to see USC, who featured black athletes, whip up on a team that did not allow them to play, who played for a school that did not want to grant them admission. When USC’s bus drove through the black communities, people lined the streets to root them on.

As game time neared, Alabama players and fans were surprised to see the amount of black players on USC’s roster. USC had an all black backfield, which included Jimmy Jones, a black quarterback.

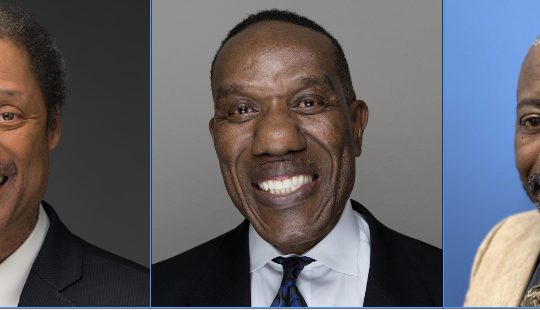

Alabama players and fans were even more surprised to see running back Sam Cunningham, who is black, run right over and right by Alabama defenders as if they did not belong on the same field with him. The all white Alabama defenders were no match for the size, strength, and speed Cunningham possessed. On only 12 carries Cunningham rushed for 135 yards, and he had two touchdowns in the first quarter alone.

The final score was 42-21 in favor of USC, but that game was over from the first half, and the all white crowd at the game could only sit there in shock, watching what black athletes were capable of doing.

In a roundabout way, Cunningham single handedly ended segregation on Alabama’s football team. After the game was over, Bryant said to USC head coach John McKay, “I can’t thank you enough for what you did for me today.”

Bryant was alluding to his desire to recruit black players, and that getting blown out at the hands of black players would change the culture at Alabama.

It looks like Bryant was right, because a white Alabama fan was overheard the next day saying, “We need a Sam Cunningham.”

The very next year Alabama had a black player on their roster, and now 40 years later, nearly their entire team is black.

Governor George Wallace was correct when he said, “Segregation today, segregation tomorrow…” But he was wrong when he said, “Segregation forever.” Seeing that Alabama has won six national championships since they brought in black players, the folks in Alabama should be thankful that he was wrong. Well, at least in terms of college football.

Check out the Sentinel Sports Section on Facebook and Twitter.

Sentinel Sports Section Facebook page:

http://www.facebook.com/?ref=logo#!/pages/Los-Angeles-Sentinel-Sports-Section/137328139648009

Sentinel Sports Twitter page: