It’s never too late to embrace your passions and make your life a work of art—as Bill Traylor did.

Born circa 1853–1949, Traylor created an extensive body of graphic artworks during his eighties, over a span of 5 years. He is among the most important American artists of the 20th century having lived through the Civil War, Emancipation, Reconstruction, Jim Crow segregation, the Great Migration and the steady rise of African American urban culture in the South.

Born in antebellum Alabama, Traylor was born into slavery, the son of Bill and Sally Calloway, on the plantation of George Hartwell Traylor. After emancipation in 1863, he stayed on the plantation working as a farmhand and sharecropper. After two marriages and fathering many children, and eventually leaving plantation life, he moved to Montgomery, Alabama.

In Montgomery, Traylor worked at a shoe factory, but rheumatism ended his working and he struggled to make ends meet. Through government assistance and shelter at the Ross-Clayton Funeral Home, Traylor found some relief. It was on Monroe Street, which was the hub of the Black neighborhood in downtown Montgomery, that his art career would begin. He began to draw pictures on any available cardboard or paper.

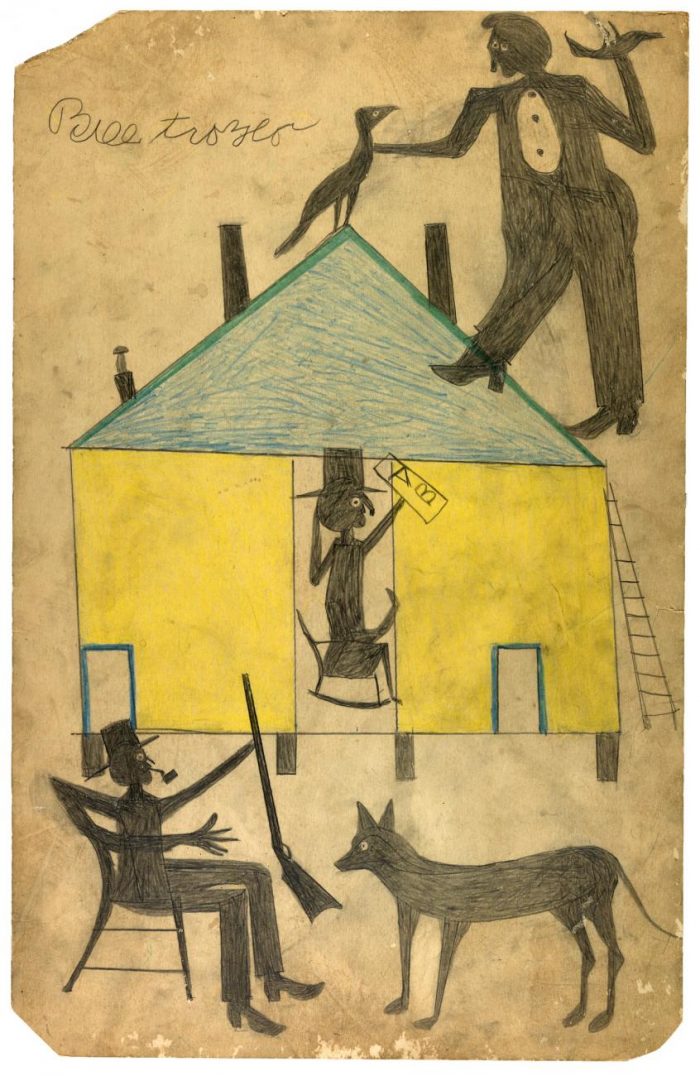

Using pencils, crayons, charcoal and straight-edged stick on discarded shirt cardboard, the self-taught artist created a visual autobiography of images extracted from his memories and experiences. His pictures depicted life on the plantation and urban life in general. Traylor also drew animals—rabbits, dogs, cows, birds in daily life. Most of his drawings of people were shown wearing accessories like a cane, pipe, top hat, or purse either standing still, as silhouettes, or drinking, dancing, conversing, or arguing with another person.

He was discovered by artist Charles Shannon in Montgomery, Alabama in 1939. Shannon purchased some of his drawings and began supplying Traylor with materials. In 1940, he arranged an exhibit featuring 100 of Traylor’s works at the New South Gallery and School in Montgomery. He organized another exhibit of Traylor’s work in 1941 at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in Riverdale, New York. In 1942, Shannon left Montgomery to serve in World War II and had acquired some 1,200 of Traylor’s works.

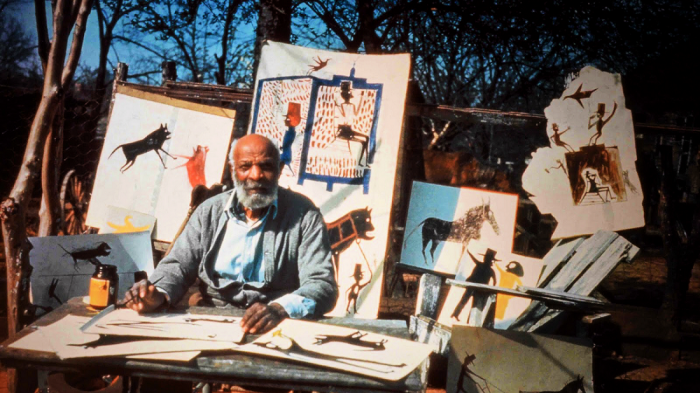

Photo Courtesy of americanart.si.edu

Traylor eventually went to live with a daughter in Detroit and relatives in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, Traylor developed gangrene and had to have his left leg amputated. He later returned to Montgomery in 1946 to live with another daughter and later, to a nursing home, where he passed away. The only known works by Traylor were undated, but produced between 1939 and 1942.

When he died in 1949, Traylor left behind more than 1,000 works of art. The 1982 exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art entitled “Black Folk Art in America” brought Traylor to national attention as a major artist and visual storyteller.

The critically acclaimed exhibition “Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor” will remain open to the public through Sunday, April 7 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The exhibition brings together 155 drawings and paintings from 51 public institutions and private collections.

Organized by Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the exhibition presents a comprehensive picture of Traylor’s stylistic development and artistic themes, explored in the context of the profoundly different worlds Traylor’s life bridged: rural and urban, black and white, old and new.

“It is only with extraordinary effort and cooperation that an exhibition of this magnitude can be extended, and in this case, we were fortunate to have many like minds share the belief that Bill Traylor’s most shining moment should not be cut short,” said Umberger.

“Rarely do the stars align to allow us to extend an exhibition of this scale with so many lenders from around the country and the world,” said Stephanie Stebich, the Margaret and Terry Stent Director at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “We are deeply grateful to the collectors, museums and foundations—each and everyone one of whom agreed to extend their loan—for their continued generosity in sharing these important works with the American public.”

Brian W. Carter contributed to this article.