The Million Man March/Day of Absence was clearly a historic event with enduring meaning for us as a people. It was rightly posed in its Mission Statement as “a timely and necessary statement of challenge, both to ourselves and the country, in a time of increasing racism, attacks on hard-won gains, and continually deteriorating conditions of the poor and the vulnerable, and thus, an urgent time for transformative and progressive leadership.” Moreover, the March and its companion project the Day of Absence was a reaffirmation of the fundamental principle and constant practice that we are our own liberators and “that no matter how numerous or sincere our allies are, the greatest burdens to be borne and the most severe sacrifices to be made for liberation are essentially our own.”

Especially was it “an example and encouragement of operational unity,” a concept I advanced in the midst of the Black Liberation Struggle in the Sixties. Indeed, operational unity was a call for unity in diversity, unity without uniformity and unity in principle and in practice. Clearly, Min. Louis Farrakhan is to be credited with the insightful concept and timely call for the March and the Nation of Islam for providing the foundational organizational support for the March. But it was through operational unity and the mobilizing and organizing efforts of local organizing committees in over 318 cities which ensured the success of the March and the Day of Absence.

The Million Man March/Day of Absence Mission Statement, which I wrote as a summary consensus of the Executive Council of the Organizing Committee, stands as an essential and enduring public policy document and way forward in the ongoing and now intensified struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves and live the good and meaningful lives we deserve and demand. It offers an agenda enduringly real and relevant. And on this 25th Anniversary of the March, it is important to raise it up and extract the lessons learned from its Mission Statement about how we can understand and assert ourselves in liberating ways in the world.

The Mission Statement intentionally starts with the phrase, “We, the Black men and women, the organizations and persons” because it wanted to affirm the fact that our project was an inclusive and united one, requiring our people as a whole for its ultimate significance and success. And therefore, although the first focus was on the self-raising and rising of Black men, it unavoidably reached out to and included Black women and the Black community as a whole. For we reasoned that real liberation and a good and meaningful life, must be the will and work of the whole people. Now, the priority need and call for Black men to stand up and assume a new expanded sense of responsibility was based on the common consensus that the health and well-being of our community depended on it. For not only were Black men indispensable to family, community and our liberation struggle, but also “some of the most acute problems facing the Black community within are those posed by Black males who have not stood up” and assumed their needed and rightful responsibility.

Thus, we reasoned and said in the Mission Statement that “unless and until Black men stand up, Black men and women cannot stand together and accomplish the awesome tasks before us.” But given understandable concern that this priority emphasis on Black men not disadvantage or minimize concern for Black women, we stated that this priority emphasis on Black men standing up is made “without denying or minimizing the equal rights, role and responsibility of Black women in the life and struggle of our people.” Thus, we reaffirmed the indispensable unity of our people, the moral necessity of shared respect and responsibility in all we do and dare as persons and a people.

We raised three basic themes: atonement, reconciliation, and responsibility. Atonement was defined as engaging in self-criticism and self-correction, “being humble enough to admit mistakes and wrongs and bold enough to correct them.” Reconciliation called for settling disputes, stopping character assassination, overcoming conflicts, putting aside grudges and hatreds in our relationships and organizations and between our organizations, rejecting personal and communal violence, and building and sustaining loving mutually respectful and reciprocal relations in the interest of our lives, our work and our struggle. And responsibility called for us to stand up and stand together in liberating practice as conscious and committed men and women.

Our demands were public policy positions. And we called for reparations in the fullest sense of the concept: public admission, public apology, public recognition; compensation and discontinuation of oppressive practices. And, of course, this means a radical reconstruction of society. We also called for a halt to criminalizing our people and undoing hard-won gains, such as affirmation action and voting rights, to halt the privatization of public wealth and space, spend money on education, not imprisonment, and protect and preserve the environment.

We called for universal, full, and affordable healthcare, affordable housing, passing of the Conyers’ Reparations Bill (HR 40), an economic bill of rights, and plans to rebuild devastated urban areas. Also, we called on our people to continue the struggle against police abuse, government suppression, violations of civil and human rights, and the industrialization of prisons. And we called for support of the freedom of political prisoners, prisoners’ rights and their efforts of self-transformation in returning to society.

Moreover, we reaffirmed our standing in pan-African solidarity and struggle with African peoples everywhere and with Native Peoples, and other peoples of color in their just and liberation struggles. And we called on corporations to respect the rights and dignity of working peoples, to reinvest profits back into the Black community, and to stop plundering, polluting and depleting the environment.

In addition, we called on our community to practice an active, aware and independent politics, rebuild and expand its economic base, and above all rebuild and strengthen the Black family and community to struggle to reduce and end poverty, increase employment, achieve a culturally-grounded quality education, and enhance our institutional and organizational capacity to define, defend and advance our interests as a people. We also placed strong emphasis on supporting and challenging our faith communities to put forth the best of our values and practices as a moral and social vanguard in this country and the world. And we committed ourselves to embrace and practice in our daily lives the Nguzo Saba (The Seven Principles): Umoja (Unity); Kujichagulia (Self-Determination); Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility; Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics); Nia (Purpose); Kuumba (Creativity) and Imani (Faith).

Noting the historic character of the moment and of our project, we stated in conclusion that “in standing up and assuming responsibility in a new, renewed and expanded sense, we honor our ancestors, enriches our lives, and give promise to our descendants.” This, of course, is a reaffirmation of the Kawaida contention that this is our duty: to know our past and honor it; to engage our present and improve it; and to imagine a whole new future and to forge it in the most ethical, effective and expansive ways.

And on this, the 55th Anniversary of the Organization Us, we raise up and remember this historic March and Day of Absence and the role of our men and women who played a key role in it.

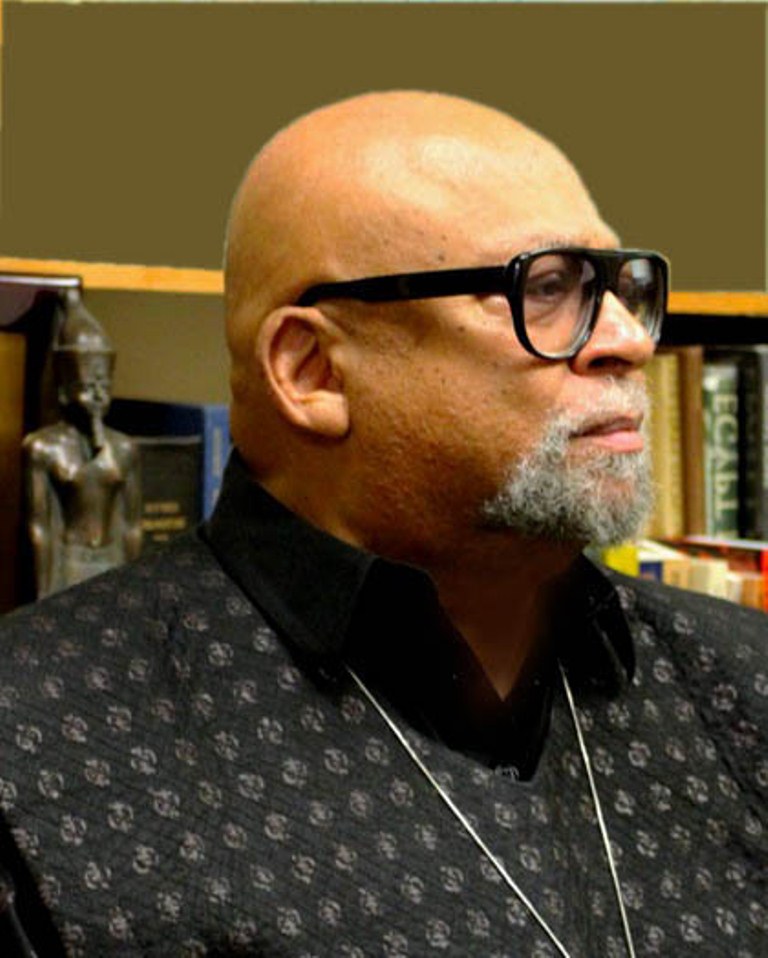

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.