The white men who chased and killed Ahmaud Arbery as he ran on a residential street remained free for more than two months, with police and prosecutors appearing to accept their story that the young Black man was a fleeing criminal who turned and attacked before being fatally shot.

Two years after Arbery fell dead on Feb. 23, 2020, the trio responsible for the deadly pursuit has seen its version of events rejected in court. After two trials held a few months apart, the three men have been convicted not only of murder, but also of federal hate crimes.

Amid a national reckoning over racial injustice in the criminal legal system, the back-to-back guilty verdicts have bolstered Arbery’s family and local activists who initially feared the killing just outside the Georgia port city of Brunswick might go unpunished.

“It shows that there’s hope for our justice system,” said the Rev. John Perry, who was president of the Brunswick NAACP chapter when Arbery was killed. “I don’t think it’s an absolute game changer.”

Activists are hoping for a similar outcome in Minneapolis, where jurors started deliberating Wednesday in the federal trial of three fired police officers charged with violating George Floyd’s civil rights. Floyd, a Black man, died on May 25, 2020, when then-officer Derek Chauvin pinned him to the ground and pressed a knee to his neck for what authorities say was 9 1/2 minutes.

Arbery’s mother, Wanda Cooper-Jones, attended an event honoring her son on the second anniversary of his death Wednesday in Atlanta, where state lawmakers passed a resolution declaring Feb. 23 Ahmaud Arbery Day in Georgia.

“When we hear the name of Ahmaud Arbery, we will now hear and think of change,” Cooper-Jones told those in attendance.

About 50 supporters joined one of Arbery’s aunts, Thea Brooks, Wednesday evening in a procession through the Satilla Shores subdivision where Arbery was killed less than 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) from his home. They chanted, “I run with Maud!” _ a phrase that became the family’s rallying cry after his death.

Shanesha Sallins walked toward the back of the group. Her mother and Arbery’s mother worked together, she said, and Arbery often jogged past her home nearby.

“I just hope this is a lesson for a lot of Southerners,” Sallins said of the legal convictions, though she’s unsure whether they signal lasting change. “It’s a start. But once the lights turn off and everybody goes back to their normal lives, the system’s still broken.”

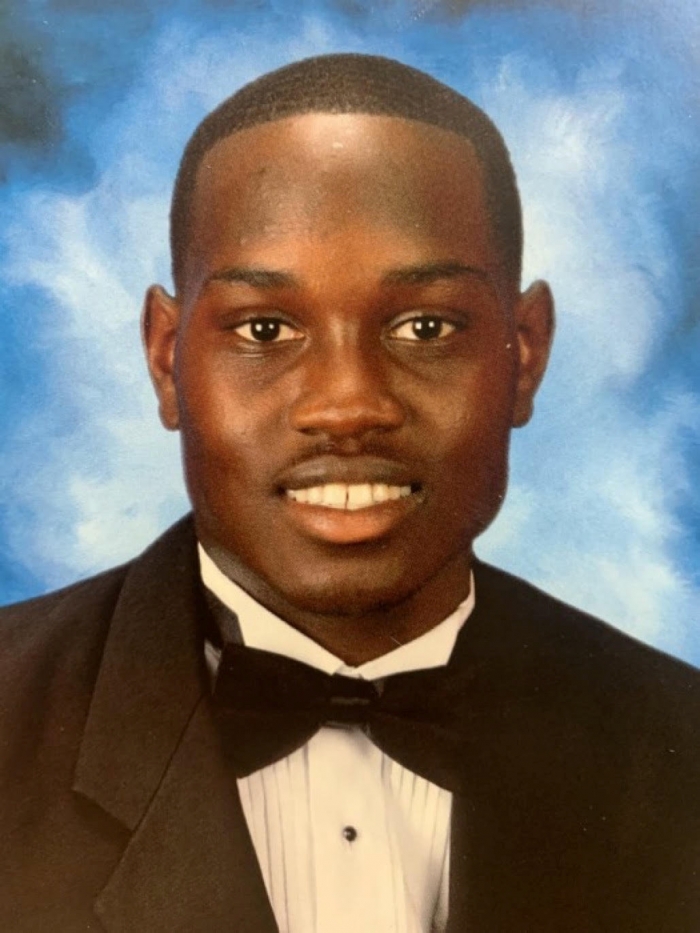

Arbery had enrolled at a technical college and was preparing to study to become an electrician, like his uncles, when he was killed at age 25. His parents stopped short of calling the hate crime verdicts delivered by a jury Tuesday a victory, noting the convictions won’t bring back their son.

Still, many in Brunswick and surrounding Glynn County, a community of nearly 85,000 where Black residents make up 26% of the population, saw the trials over Arbery’s killing as a test of the justice system as well as an opportunity to confront what they saw as blatant racism.

Father and son Greg and Travis McMichael armed themselves and used a pickup truck to chase Arbery after spotting him run past their home on a Sunday afternoon. A neighbor, William “Roddie” Bryan joined the pursuit in his own truck and recorded cellphone video of Travis McMichael blasting Arbery with a shotgun.

Despite the men’s suspicions that Arbery was a criminal, investigators found no evidence he had stolen anything or committed other crimes in the neighborhood. Travis McMichael testified at the murder trial that he opened fire in self-defense after Arbery attacked with his fists.

Evidence in the weeklong hate crimes trial included roughly two dozen text messages and social media posts in which the men used racist slurs and otherwise disparaged Black people. Bryan mocked the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday and reacted bitterly upon learning his daughter was dating a Black man. Travis McMichael complained that Black people “ruin everything” and commented on a video showing a Black man playing a prank on a white person: “I’d kill that f_-ing n__r.”

Travis Riddle owns a Brunswick soul food restaurant where a framed photo of the sheriff arresting Greg McMichael in May 2020 hangs on the wall. Riddle, who is Black, said he hopes exposing the racism espoused by the McMichaels and Bryan will make others who are like-minded hesitant to share their views.

“There’s other people who think what they did was right, but with the outcome of this case, they’re going to suppress those thoughts and those actions,” Riddle said. “Brunswick has shown them twice we’re not with this.”

The legal fights aren’t over. Former District Attorney Jackie Johnson, ousted in 2020 by voters who blamed her for the delayed arrests in the Arbery case, was indicted last year on misconduct charges alleging she used her office to protect the McMichaels.

Greg McMichael had worked for Johnson as an investigator and left her a phone message after the shooting. Johnson has denied wrongdoing, insisting she immediately handed the case to an outside prosecutor. Her case is pending in Glynn County Superior Court.

“There was a major collapse in our system that allowed a young man’s life to be robbed,“ said Perry, the former NAACP leader. “Our system failed to make an arrest. Responsibility lies somewhere, and I think this investigation is an honest attempt to find out where the breakdown happened.”

Brunswick activists have also pushed for reforms to the Glynn County Police Department. Its investigation into Arbery’s death languished until May 2020, when the graphic video of the shooting leaked online and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation took over the case.

County commissioners last summer hired the department’s first Black police chief after agreeing to a national search. A Better Glynn, a local group formed after Arbery’s death to promote racial and socioeconomic justice, had pressed officials to search for candidates outside Georgia.

The group is still urging commissioners to create a citizen review board for the police department, a proposal that’s seen no action over the past year.

“We’re not necessarily going to be out here changing a lot of hearts,“ said Elijah Bobby Henderson, one of the group’s founders, “but we’re going to change a lot of policies.”

___