In third world countries – let’s take Nigeria and Haiti as examples – electricity blackouts are routine.

Power outages sometimes last for more than a week in Haiti, where only about 25 percent of the Caribbean nation’s 10.9 million people are connected to the power grid.

And in Nigeria, a country more than 200 million people call home, power companies provide electricity to only 45 percent of households. Losing power about once a day in the West African nation is the norm.

But in the United States, 100 percent of households have access to electricity. More than 95 percent of power outages are weather-related – and they only last, on average, between 4 to 7 hours, according to the United States Department of Energy.

That’s one reason, the recent massive, pre-planned Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) blackout two weeks ago in California, the wealthiest state in the nation, was not only upsetting to most people, but also hard to accept and widely criticized.

“For years, PG&E has done a poor job on maintenance and tree clearing, and they’re still not even close to where they need to be,” said Sen. Bill Dodd (D-Napa), whose district was impacted by the blackout. “That fact, along with breakdowns in communication, are unacceptable. Sadly, poor performance by PG&E is par for the course, so it’s not surprising.”

The company is the largest electricity and natural gas power provider in the state serving some 16 million people from Santa Barbara and Kern counties in the South, up north to the Oregon state line, and east to the Nevada and Arizona borders.

The P&G power outage, which lasted from Oct. 9 through Oct. 12, has been linked to three deaths. It affected more than 700,000 Californians in 35 counties and cost residents, businesses and the public sector over $2 billion dollars.

The blackout, the seventh scheduled one this year, impacted 39 hospitals, too.

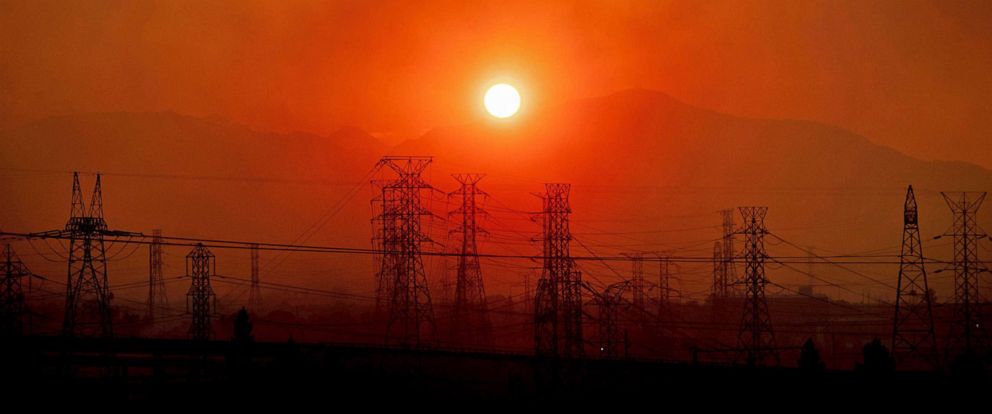

PG&E resorted to cutting power, company spokespeople and executives explain, in designated areas of the state. Because the National Weather Service predicted heavy winds, high temperatures and dry air, the company feared those conditions would lead to disastrous wildfires if power lines – many of them supported by aging, worn-out transmission towers – were downed. They could spark, setting the dry vegetation ablaze, which could result in deaths and the destruction of property.

Last week, Gov. Newsom called the power outage “unacceptable.”

“Californians should not pay the price for decades of PG&E’s greed and neglect,” said Governor Newsom last week, slamming the investor-owned utility. “We will continue to hold PG&E accountable to make radical changes – prioritizing the safety of Californians and modernizing its equipment.”

Even as the utility company, one of the largest in the country, faces sharp criticism from state officials, it is defending its decision to cut power as a safety measure. PG&E also cautions that it may have to schedule rolling blackouts for the next 10 years while it updates equipment.

In a hearing before the California Utilities Commission (CUP) Friday, PG&E CEO Bill Johnson, along with nine other company executives, admitted the company’s shortcomings during the blackout and apologized for them. They also assured state officials that PG&E is taking measures – including updating its equipment, using technology to limit the target area of future blackouts and trimming trees near transmission towers – to minimize outages and prevent wildfires.

“We recognize the hardship that the recent public safety power shutoff event caused for millions of people and want to continue working with all key shareholders to lessen this burden going forward,” Johnson wrote in a letter to the PUC. “At the same time, we ask our customers, their families, and our local and state leaders to keep in mind that statistic that matters most: there were no catastrophic wildfires.”

PG&E is currently facing a number of uphill battles in California.

The utility provider is taking steps to emerge from bankruptcy after facing more than $30 billion in liabilities for wildfires (far more than its total revenue in 2017, which was $17.4 billion). The worst was last year’s Camp Fire, the deadliest in the state’s history, which resulted in the deaths of 86 people, gutted more than 18,000 buildings and ravaged more than 150,000 acres of land, including the town of Paradise in Butte County.

Under California’s Inverse Condemnation rule, utility providers like PG&E are held fully liable for wildfires or other public or personal damage their equipment may cause whether that company acts negligently or not. And if a power company tries to share the burden of its liability with customers through rate increases, it must prove under California Public Utilities Code 463 that it did not incur those costs because of an “unreasonable error” in its planning, construction or operation.

Then, two weeks ago, a California judge ruled that PG&E will no longer have exclusive control over its bankruptcy process, a decision that caused the price of its shares to tank by about 32 percent. In January, when it filed bankruptcy, stocks dropped by about 52 percent.

Since the blackout began, Gov. Newsom, state officials and customers have continued to express frustration with how much the blackout has cost customers. In fact, the governor is urging the company to pay each of its residential customers $100 and each small business $250 through automatic credits or rebates.

Critics are also blasting the utility company for the way it handled not only the disruption of service but also its customer service response and public relations activity related to the blackout.

At Friday’s hearing, Marybel Batjer, president of the California Public Utilities Commission, echoed the governor’s irritation.

“You guys failed on so many levels on pretty simple stuff,” Batjer said, pointing out that the company’s website, which many of its customers were relying on for information pertaining to the blackouts, crashed.

“What we saw play out by PG&E last week cannot be repeated,” she said. “The loss of power endangers lives.”

Many PG&E customers who lost power say the lack of updates from the company was appalling, and they are now worried that blackouts could be more frequent in the state.

“I’m not happy with PG&E at all,” Santa Cruz County resident Satya Orion told local KSBW TV News. “We did not get notified after the first warning. What if someone has a medical device that needs to keep running?”