The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe has garnered nationwide attention with its months-long protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL).

Stories emanating from the scene are reminiscent of 1960s civil rights marches, with protesters attacked by guard dogs, pepper spray and bean bags. While law enforcement insists public safety must be maintained, tribal officials counter that the DAPL project must be stopped because it can potentially endanger their primary water source.

The heated and sometimes violent disagreement stems from Energy Transfer Partners LP’s construction of a 1,172-mile pipeline that spans four states carrying up to 570,000 barrels of oil each day. The route would cross under Lake Oahe in North Dakota; a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project on the Missouri River located one-half mile south of the Standing Rock Reservation.

Since, 200 Native Americans on horseback mounted the first protest in April, thousands more have descended on the site including celebrities, activists and veterans, in support of Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Their outcry may have been a factor in the Dec. 4 announcement by the Corps of Engineers that they will not approve an easement that would allow the proposed Dakota Access Pipeline to cross under Lake Oahe.

Jo-Ellen Darcy, the Army’s Assistant Secretary for Civil Works, said in a statement, “Although we have had continuing discussion and exchanges of new information with the Standing Rock Sioux and Dakota Access, it’s clear that there’s more work to do. The best way to complete that work responsibly and expeditiously is to explore alternate routes for the pipeline crossing.”

In announcing the Army Corps’ decision to the protesters, the New York Times reported that Dave Archambault II, the chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, said, “You all did that. Your presence has brought the attention of the world. We wholeheartedly support the decision of the administration and commend with the utmost gratitude the courage it took on the part of President Obama, the Army Corps, the Department of Justice, and the Department of the Interior to take steps to correct the course of history and to do the right thing.”

However, Energy Transfer Partners responded in a statement that they “fully expect to complete construction of the pipeline without any additional rerouting in and around Lake Oahe. Nothing this Administration has done today changes that in any way.”

As the dispute plays out on a national stage, local Native American organizations and civil rights activists voiced their support to the position of the Standing Rock Sioux as well as commented on some of the broader issues the protest brings to light.

“Americas first people are often times disenfranchised, unheard, and are the most disadvantaged populations in the country,” said Joseph Quintana of the United American Indian Involvement (UAII), which has an office in downtown L.A.

“The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe has decided that as a community they will not accept the potential for contamination of a primary water source, along with the communities that follow along the rivers path. I support their decision as does my organization, which serves over 170 different tribes, from all across North America.”

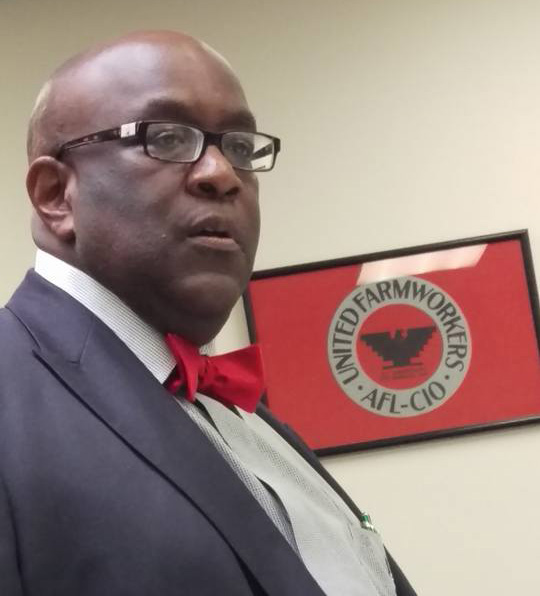

Pastor William Smart, president/CEO of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference of Greater Los Angeles, noted the similarity of the pipeline protest to past and current civil rights protests by African Americans.

“I see comparison because there are always racist determinations behind economic decisions of multinational corporations and the government. Native Americans were the first people in this country and they endured a cycle of genocide that has continued in various capacities, through Black, Yellow, and Brown people,” said Smart.

Citing the importance of accurate reporting of the protest, Frank Blanquet, chief content manager for First Nations Experience, FNX Network, said “As an Indigenous media channel we knew this was something we needed to go out and cover [the story] to the best of our ability. We knew local mainstream media was quoting and reporting based on the Mandan Sheriff Office’s accounts, yet our own media and tribal contacts at Standing Rock had information that conflicted with such reports.

“As an example the sheriff at one point said that there were pipe bombs and shots fired, a statement that was never proven or corroborated, yet no retraction was ever made. So our position became one of shedding light on the truth.”

Both UAII’s Quintana and SCLS’s Smart encouraged African Americans and other ethnicities to consider backing the efforts of the Standing Rock Sioux to stop the pipeline construction.

“African Americans are descendants of tribal people who understand these cultural aspects of perceiving the world around them with respect. For movements or causes brought on by American Indian Tribes, we must also educate the community, rely on support from all people, while leading and taking ownership of the cause,” said Quintana.

Smart added, “We have to work together as people who are oppressed, so that as we struggle together, we will be victorious. There will always be some form of fight that groups of color will have to go through to get gains in this country.”