A group that oversees the St. Louis school desegregation program is discussing an option that would end the nation’s largest and longest-running desegregation effort.

Superintendents and representatives of 12 participating school districts met Thursday to begin planning for the potential change to the program, which has allowed more than 60,000 black students in St. Louis to attend suburban schools during the last several decades.

It is a legal requirement that the program eventually end, according to David Glaser, executive director of the Voluntary Interdistrict Choice Corporation, which oversees city-county transfers. If the board votes later this year to approve the change, it would start in the fall of 2019, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported (http://bit.ly/1XdPHaA ).

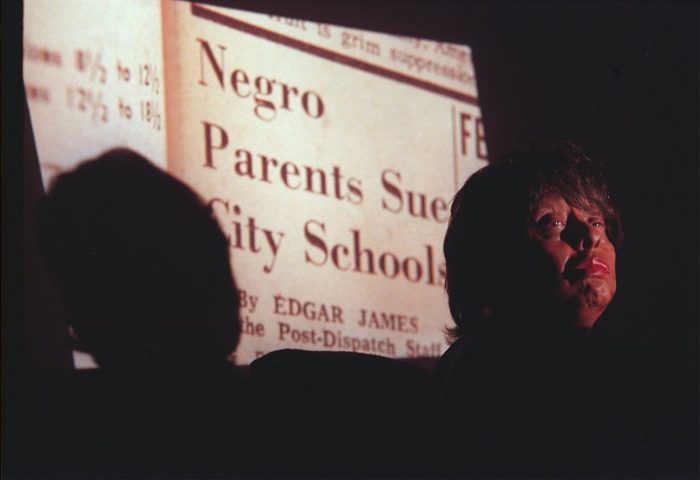

All students who are currently in the program could continue through graduation. Black students from St. Louis began attending predominantly white schools in St. Louis County in the early 1980s as the result of a federal school desegregation lawsuit. The program also allowed white students from the county to attend city magnet schools.

About 4,583 black students from the city transferred last school year, while about 140 white students transferred to city magnet schools. But several school districts have stopped accepting transfer students through the program: The Pattonville School District stopped because of its shifting demographics, while the Kirkwood School District began only accepting the siblings of students already enrolled last year because of a lack of classroom space.

“It’s sad that it’s ending,” Kirkwood schools’ superintendent Tom Williams told the newspaper. “For Kirkwood, having that diversity has been really rich for all our kids.”

The option to attend suburban schools continues to be popular among black families in the area, Glaser said, noting there are around 3,000 applications this year for about 650 open seats in county schools this fall.

“It’s done what it’s expected to do,” St. Louis Public Schools superintendent Kelvin Adams said of the desegregation program. “It’s given students in the city the chance to interact with students in the county. It’s a program that’s been around a long time and that benefits students in both places.”

A study released by the corporation in 2012 showed transfer students showed little academic advancement in elementary school, but steady improvement in high school in reading and math. Earlier this year, the governing board of St. Louis Public Schools approved a contract with Jerome Morris, a professor of urban education at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, and its Public Policy Research Center to look into desegregation’s effects and recommend policies.