In the midst of our and other ongoing struggles for liberation, freedom, justice and other indispensable and indivisible goods in the world, I turn constantly to the sacred texts of our ancestors for grounding and guidance, for constantly deepening insight, urgently needed answers, and uplifting and liberating inspiration. This is especially important to me, to Us, in these difficult, dangerous and demanding times in which evil seems ascendant, shape shifting oppression appears ever-enduring, genocide is shamelessly “justified” by the would-be “superior” and “civilized,” and righteous resistance is denounced and outlawed on campus, in Congress and society.

But still we must bear witness to truth and set the scales of justice in their proper place especially among the voiceless, devalued, downtrodden, dispossessed and oppressed. And this requires resistance, righteous and relentless struggle to oppose evil, injustice and oppression, to affirm and enhance the good in us and the world, and to aspire to, in imagination and action, a whole new world of shared and sustained good.

Clearly, for the members of Us, the sacred texts, the Husia of ancient Egypt and the Odu Ifa of ancient Yorubaland are, as the Husia teaches, a sacred gift of “that which endures in the midst of that which is overthrown.” And as the Odu Ifa states, it is teachings of a vital truth, a truth that “guides rightly, cannot fail, cannot be ruined” and is “a great power” in the world and “an everlasting good” (219:1).

Thus, both sacred texts teach us, urge and inspire us to focus on and continue to wage struggle. And this waging of righteous struggle is laid out and lifted up as a moral imperative and a transformative and liberating good. Although both the Husia and Odu Ifa offer excellent lessons on the moral imperative and moral good of struggle, I want to share insights from the Odu in this discussion.

Now, the Odu teaches the value of both internal struggle and external struggle. But I want to focus on external struggle while not minimizing the importance of internal struggle which is indispensable to the quality and success of the external struggle. The Odu tells us that struggle is essential to life, to our growth, to our success, well-being and flourishing in life and our victory over evil, injustice and oppression.

In regard to internal struggle, the Odu stresses the need for humbleness saying that given the demands of growth, development and good in the world, “We are constantly struggling, all of us. We are constantly struggling” to grow, to develop, flourish and come into the fullness of ourselves (10:6).”

But given the need to create the conditions and capacities for human good and the well-being of the world, and to overcome evil, injustice and oppression, we must wage righteous and relentless struggle. Indeed, the Odu (78:1) states we should engage life and struggle with joy, saying “Let’s do things with joy. . . For surely humans have been divinely chosen to bring good in the world.”

And this, Kawaida teaches, is the fundamental meaning and mission of human life. As the sacred text says later, we are also to struggle to not let any good be lost. Indeed, in the same chapter, it says that what is needed to achieve a good world is “the eagerness and struggle to increase good in the world and not let any good be lost.”

Now, if the struggle we wage is to be a good and meaningful struggle, we must always be rightfully attentive to its character and conduct, the Odu Ifa teaches us to commit ourselves to this teaching, i.e., “May the struggle we wage always add to our honor.” We read this concept of adding to our honor (iyi) as expanding and enriching our sense of ourselves and increasing the respect of significant others for us. The Yoruba word, iyi, means respect that we gain in the way we conduct ourselves, urging us be attentive to the moral means and goals of our struggle.

Here Nana Amilcar Cabral reaffirms this teaching when he speaks of our liberation struggle saying, “if national liberation is essentially a political problem, the conditions for its development give it certain characteristics which belong to the sphere of morals.” And Nana Dr. Anna Julia Cooper teaches us that while not denying our own peoplehood, we must “take our stand on the solidarity of humanity, the oneness of life and the unnaturalness (emphasis mine) of all favoritism (all oppressive sentiments, thought and practice) whether of sex, race, condition or country.” She thus defines freedom, justice and equality as natural and unfreedom, injustice and inequality as unnatural and compelling righteous and relentless resistance.

The Odu Ifa also teaches moral and psychological courage in struggle, the courage to hold moral ground in the midst of the powerful and oppressive majority or minority. The teachings harshly criticize the way of the coward, who bends with the wind, spits in the air to see which way the popular wind is blowing and walks that way. And the coward, the sacred text teaches, is one who “runs on the day of battle,” “who breathes in fear and who is half-dead before the struggle begins (153:1; 204:1).”

In contrast, the courageous one imitates and embodies the courage, commitment and steadfastness of the lion. They are in the tradition of the Simba Wachanga, the Young Lions of Us in the 1960s, and all the lions, young and old, who preceded us and made us possible, lion-hearted and lion-minded. To be Simba-hearted and Simba-minded for Us, then, is to be noble in conduct, courageous in combat, and uncompromisingly committed to victory that adds to our honor. Thus, again, the text teaches, the struggles we wage must add to our honor and “the battle, the struggle, that brings honor belongs to the lion (150:2).”

Also, the sacred text Odu Ifa teaches us that in our struggles we must be thoughtful. That is to say, giving careful consideration in both the moral and rational sense. In the moral sense, this means moral sensitivity to others and especially in struggle, not to be morally blinded by hate or have a depraved disregard for the life, well-being and interest of others. In verse 170:1, there is an emphasis on the need to respect human life in our struggle for liberation and good in the world.

And the text suggests that weighed against the heavy value of preserving human life, other issues are as light as a basket of dry leaves. Indeed, the text (170:1) says, “a basket of dry leaves is not heavy enough that its content should cause the death of a human being.” This recalls Nana Cabral’s teaching that we must be “reluctant soldiers”, never ever committed to antagonistic struggle or war as a way of life or imitate the genocidists whose bloodlust knows no end and admits no ethics. And as Nana Dr. Martin Luther King taught, as Kawaida interprets, our highest aim is to struggle in ways that win allies not leave victims, especially among ourselves.

Furthermore, the Odu Ifa teaches us that we must persevere in our ongoing righteous and relentless struggle for a good world. We must, it says, “be able to suffer without surrendering and persevere in what (we) do (150:1).” And we must, the Odu Ifa teaches us, sacrifice in the self-strengthening practice of self-giving. In Kawaida, sacrifice, as self-giving, is a dedicated and disciplined giving of our heart and mind; our efforts; our time; our resources; and eventually the wholeness of ourselves to the struggle for good in and for the world.

Finally, the sacred texts of Odu Ifa tells us we must be constant soldiers in the struggle in the interests of human good and the well-being of the world and all in it (199:1). It defines this soldier saying, “a constant soldier is never unready, not even once.” Indeed, the sacred text says, “One who stands ready to act for the good is supported by Ogun (the divine spirit of righteous struggle) on the day of battle (185:1).” The constant soldier knows with Nana Haji Malcolm that “wherever there are Black people, there is a battleline.”

And thus as we say in Kawaida reaffirming this, “Everywhere a battleline; every day a call to struggle.” And these constant soldiers know that the struggle is worldwide as the Odu teaches saying, we are all divinely chosen to increase and sustain good in the world. And bringing good in the world requires that we accept the teaching of Nana Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune that “We must remake the world. The task is nothing less than this.” Ase. Ase. Ase.

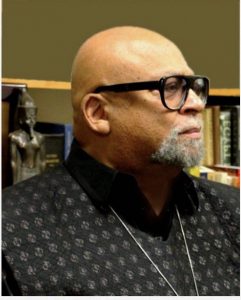

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.