It was a beautiful and uplifting gathering of all-seasons soldiers, activist intellectuals, movement lawyers, institution-builders, and consistent servants of African peoples, assembled at the African American Cultural Center (Us)’s virtual forum, Sunday, to pay rightful homage to Nana Randall Robinson whose life, work and struggles embodied all these identities and active commitments.

Sharing deep memories and reflections were Atty. Adjoa Aiyetoro, Atty. Nkechi Taifa, Atty. Èzili Dantò, Mr. Mel Foote, Dr. Haki Madhubuti and this author. We spoke of the amazing measure and enduring meaning of this African man who rejected and resisted America’s refusal to respect he said, “The ancient, full African whole of me” and who gave his life to the defense, dignity and liberation of African peoples everywhere. Remembering and reflecting on how we knew and worked with him and in the Movement and on the lessons offered by his life’s work and legacy, we reaffirmed his heavy weight and worth in the scales of African and human history.

And as we say in tambiko in the tradition of our ancestors: May the joy he brought and the good he left last forever. May his wife, Hazel Ross Robinson, and his children, Khalea Ross Robinson, Anike Robinson and Jabari Robinson, and all his family and loved ones be blessed with consolation, courage and peace. For surely, Nana Randall has risen in radiance in the heavens and now sits in the sacred circle of the ancestors, among the doers of good, the righteous and the rightfully rewarded. Hotep. Ase. Heri. And may we honor his legacy by continuing it, i.e., the ongoing struggles for liberation of all our people everywhere.

I remember and raise up Nana Randall Robinson, first, as a pan-Africanist, dedicated to the unity, shared struggle and liberation of African peoples everywhere. He said in this regard, “I never believed my place was necessarily physically in America. I am as much a Nigerian, a Haitian, a South African, a Kittitian, a Jamaican as I am an American. There shouldn’t be these partitions between the people of the Black world. I have lived that and I have committed myself to that in everything that I’ve done throughout my life.” And so, we stand firm on this sacred ground with him, the ground of the shared good, life and liberation of our people.

Secondly, I appreciate Randall in his understanding of the grounding we must have in culture. He said, “Every people, in order to remain healthy and strong, has to have a grasp of its foundation story. Culture is a chrysalis – it is protective, it takes care of you.” Indeed, our liberation struggle has been to return to our own history and culture, to be ourselves and free ourselves and live our lives and engage the world in liberated and self-determining ways.

Thirdly, Nana Randall leaves us the lessons and legacy of mobilizing, organizing and institution-building. His policy-shaping organization, TransAfrica, as its mission statement asserted, envisioned and was working for “a world where Africans and people of African descent are self-reliant, socially and economically prosperous, and have equal access to a more just international system that strengthens independence and democracy.” It was his essential vision and transformative life work.

Also, Randall leaves us a model of the freedom fighter who loved his people and sacrificed for them willingly. He stresses the ancient and ongoing teachings of our ancestors that we must be actively and irreversibly about liberation. So, within the framework of TransAfrica, he cooperatively built with committed others the Free South African Movement and Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid and supported the Haitian people in their struggle to regain their sovereignty, self-determination and democracy and return to their own revolutionary and world-transformative history.

He was a decisive force in the freedom of Nana Nelson Mandela, in saving the life of Pres. Jean-Bertrand Aristide from a U.S. conducted coup and kidnapping, and he fasted a life-threatening 27 days to compel the Clinton administration to change its criminal policy toward Haiti and the Haitian people, saying “if there are not some principles you have that are worth dying for, then your life is not worth living.” And Nana Randall also expanded the long history of and ongoing discourse and struggle for reparations, the awesome debt owed us, into the larger African community, society and world.

It is also important to stress that Nana Randall Robinson was a family man and offers us a vital lesson on the urgent need to maintain and build our families. Indeed, it’s part of being a revolutionary and loving our people and demonstrating it in our personal relations.

Therefore, we hear from his beloved wife, co-companion and co-combatant, Hazel Ross Robinson, that “Apart from his work as a public figure, he was a very loving, dependable, protective, caring husband and father. He was a joy to know and a joy to love. He was as committed to being a source of stability and security to his family as he was to being a force for fairness and justice in the wider world. He shall be missed very, very much by me and by his family.

Finally, in remembering and missing Nana Randall Robinson, he tells us how to remember him by his life’s work and struggles, but also in a very spiritually and meaningful way. For he is in all of this a keeper of the faith and it runs through all of his work. This is powerfully expressed in words in his novel, Makeda, by the grandmother telling her grandson how to remember her.

She says to him and Nana Randall to us, “You won’t need to talk to my headstone in order to talk to me. I won’t be there. I’ll be in the air and the Earth. I’ll be in the stars that light the African heavens. I’ll be watchin’ over you and your family. My spirit will always be close enough to touch and protect you all. So, do not grieve for me. My body will die, but my soul will live on. For my soul cannot die. Always remember that my soul is the spark of God in me.”

So, let us go forward with this spirit of Nana Randall loving each other, cherishing each other, sacrificing for each other, struggling for the good with each other and leaving a legacy, like Nana Randall, worthy of the name and history African.

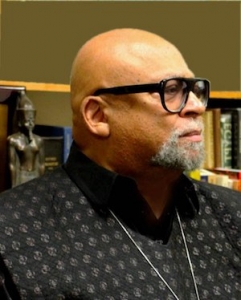

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.