As we remember and reflect on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s life, legacy and the deep meaning of his martyrdom, i.e., his awesome sacrifice and assassination, his dedication to creating a beloved community comes into full focus. For indeed, the ultimate aim of his life and struggle for the liberation of his people was not only to free them, but also to build a societal and world-encompassing beloved community of human solidarity. It is a complex and compelling vision of rightful interrelatedness and shared human good. But at the heart of it are several principles and practices which serve as its primary measure, essential meaning and definitive modes of realization. Among these are mutual respect, justice, service, sacrifice and struggle.

Dr. King comes into a context of what he calls a broken community of savage oppression, systemic racism, the absence of freedom, justice and equality, imposed poverty, war on the vulnerable at home and abroad, and White supremacist hatred and hostility imposed as public policy and socially sanctioned practice. And thus, there was a need to struggle for Black liberation, not only to free African Americans, but also to expand the realm of freedom, justice and equality, and create a shared human good for everyone.

As the King Center states, the concept of “the beloved community is a global vision of human solidarity,” a condition of life and living “in which all people can share in the wealth of the earth.” And in the newsletter of the newly established SCLC, King said the “ultimate aim of SCLC is to foster and create the beloved community in America.” Elsewhere, he stated that “Our goal is to create a beloved community and that will require a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives.” He later would define this qualitative change as a revolution of values and the quantitative change as a radical reconstruction of society.

King’s vision of the beloved community by definition begins with his complex yet accessible concept of love which I translate here as mutual respect, mutual valuing as bearers of dignity and divinity or as King says, children of God with equal dignity. He uses the Greek word agape to define this concept of love which is different and beyond romantic or friendship love. It is, he states, “understanding, creative, redemptive goodwill toward all human beings.” King clearly makes a distinction between love and liking, saying no one can be asked to like his oppressor. But he argues we must recognize them as children of God, even in their evilness. But he continues, we must resist and restrain them in their oppression of us.

I translate this as a call for mutual respect of each other as possessors of dignity and divinity as is stated in Kawaida ethical thought. The stress here on mutual respect as a key principle and practice of the beloved community is reaffirmed in King’s assertions on the interrelatedness of human life and human destiny, saying “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality tied in a single garment of destiny.” And he admonishes us in the prophetic tradition of his faith that “we must all learn to live together as brothers (and sisters) or we will perish as fools.” Again, this means the practice of mutual respect that engages every human being as valuable and valued.

Dr. King also places justice at the center of his sources and indispensable sites of the beloved community. He wants it to be ever present in our relations and exchange. He tells us we have both the right and responsibility to oppose unjust laws and unjust systems. For to remain silent and inactive in the face of injustice and unfreedom is to collaborate in one’s own oppression. Indeed, he argued “a man dies when he refuses to stand up for justice” or for what is right and true. This recalls the ancient sacred teachings of our ancestors in the Husia that says, “Doing justice is breath to the nose.” It is breath to the nose, i.e., life-giving and life-sustaining, not only to the recipient, but also to the giver.

Dr. King always links peace and justice in his vision of the beloved community. He wants peace, but not at the expense of justice. His commitment to civil disobedience and disruption of business as usual is based on his rejection of what he calls “a negative peace” and his embrace of “a positive peace.” He criticizes the White moderate as one “who is more devoted to order than to justice, who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” He also linked power and justice in his advocacy for the disempowered. Thus, he says, “power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.” And by extension, it is correcting everything in the way of creating and sustaining the beloved community.

Service is also at the heart and center of King’s vision of the beloved community. He tells and teaches us that “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is what are you doing for others?” In his classic Drum Major Sermon, he says, the greatest among us are those who serve. Thus, he asserts “everybody can be great because everybody can serve.” He states that in a eulogy for him that sums up his life, he wants to be that servant, an other-directed servant of the people, especially for the “least among us,” the vulnerable, poor, needy and oppressed. He said we should say of him that he “tried to give his life serving others, to love somebody, be on the right side of the war questions, to feed the hungry, to clothe those who were naked, to visit those who were in prison, and to love and serve humanity.”

Sacrifice is likewise central and foundational to King’s vision of the beloved community. It is part of how he conceives himself as a willing sacrifice for the liberation of his people and the good of humanity. He has measured the heavy cost that history and struggle reveal and is not deterred. He states that “Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable. Every step towards the goal of justice requires sacrifice, suffering and struggle. And this too, “Freedom has always been an expressive thing. History is fit testimony to the fact that freedom is rarely gained without sacrifice and self-denial.” Indeed, he concludes saying, “there is nothing more majestic than the determined courage of individuals willing to suffer and sacrifice for their freedom and dignity.”

Finally, then, Dr. King tells us that struggle is an indispensable motive force of history, especially our history as a people. Our resistance is first a refusal to cooperate with evil and injustice. Dr. King tells us that “it is as much a moral obligation to refuse to cooperate with evil as it is to cooperate with good.” And likewise, it is a moral obligation to struggle against injustice, oppression and unfreedom, for he says, “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor, it must be demanded by the oppressed.” And as we say in Kawaida, righteous and relentless struggle is the most decisive demand. There is in Dr. King’s vision of the beloved community and the righteous and relentless struggle to achieve it what he calls “a deep faith in the future.” It is, he says, reflected in the freedom song, “We Shall Overcome” which carries within it the deep belief in victory and a courage and commitment to see it through regardless.

In his last message to us, he promises us that “we, as a people will get to the promised land” that promised land of freedom, justice and equality and human solidarity, even though he might not get there with us. But indeed, he, like all our ancestors, will reach it when we do, for we are he and they in the present. Likewise, freedom, justice, human equality and other great goods are indivisible and shared goods, not only among the living, but also with our ancestors whose legacy we are honored and eager to embrace and extend in righteous, relentless and victorious struggle.

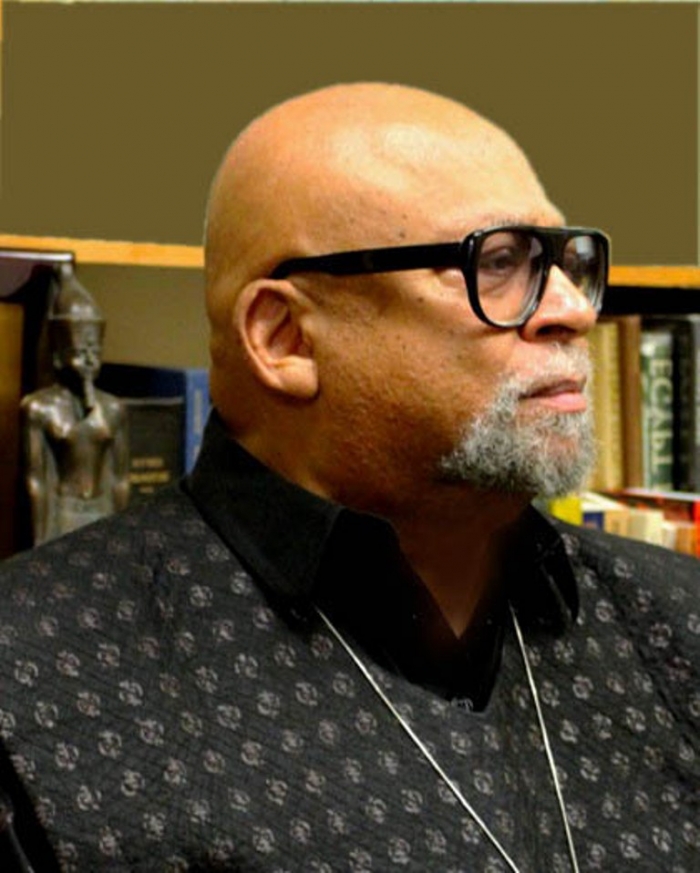

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture, | The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good Into the World and | Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.

03-30-21