No matter who you are, or where you live, there’s a central concern that links consumers all over the country: the ever-rising cost of living. For many consumers, the combined costs of housing, transportation, food, and utilities leave room for little else from take-home pay.

From Boston west to Seattle, and from Chicago to Miami and parts in between, the rising cost of living is particularly challenging in one area: housing. Both homeowners and renters alike today cope as best they can just to have a roof over their families’ heads.

The nation’s median sales price of a new home last September in 2019 was $299,400, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Even for an existing home, the St. Louis Federal Reserve noted its median price in December was $274,500.

For renters, the cost of housing is also a serious challenge. Last June, the national average rent reached $1,405, an all-time high. But if one lives in a high-cost market like Manhattan, Boston, Los Angeles, or San Francisco, a realistic rental price is easily north of $3,000 each month.

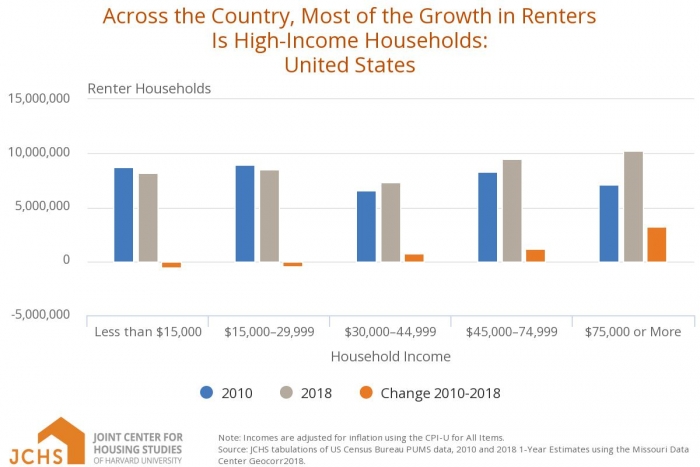

Now a new report from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) finds that the American Dream of homeownership is strained even among households with incomes most would think adequate to own a home. From 2010 to 2018, 3.2 million households with earnings higher than $75,000 represented more than three-quarters of the growth in renters in its report entitled, “America’s Rental Housing 2020.”

“[F]rom the homeownership peak in 2004 to 2018, the number of married couples with children that owned homes fell by 2.7 million, while the number renting rose by 680,000,” states the report. “These changes have meant that families with children now make up a larger share of renter house¬holds (29%) than owner households (26%).”

To phrase it another way, America’s middle class is at risk. Consumer demographics that traditionally described homeowners, has shifted to that of renters. And in that process, the opportunity to build family wealth through homeownership has become more difficult for many — and financially out of reach for others.

“Rising rents are making it increasingly difficult for households to save for a down payment and become homeowners,” says Whitney Airgood-Obrycki, a JCHS research associate and lead author of the new report. “Young, college-educated households with high incomes are really driving current rental demand.”

Included among the report’s key findings:

• Rents in 2019 continued their seven-year climb, marking 21 consecutive quarters of increases above 3.0%;

• Despite the growth in high-income White renters, renter households overall have become more racially and ethnically diverse since 2004, with minority households accounting for 76 percent of renter household growth through 2018; and

• Income inequality among renter households has been growing. The average real income of the top fifth of renters rose more than 40 percent over the past 20 years, while that of the bottom fifth of renters fell by six percent;

“Despite the strong economy, the number and share of renters burdened by housing costs rose last year after a couple of years of modest improvement,” says Chris Herbert, managing director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies. “And while the poorest households are most likely to face this challenge, renters earning decent incomes have driven this recent deterioration in affordability.”

This trend of fewer homeowners has also impacted another disturbing development: the nation’s growing homeless population.

Citing that homelessness is again on the rise, the JCHS report noted that after falling for six straight years, the number of people experiencing homelessness nationwide grew from 2016–2018, to 552,830. In just one year, 2018 to 2019, the percentage of America’s Black homeless grew from 40% to more than half – 52%.

That independent finding supports the conclusion of the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s report to Congress known as its Annual Homeless Assessment Report.

While some would presume that homelessness is an issue for high-cost states like California, and New York, the 2019 HUD report found significant growth in homeless residents in states like Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia, and Washington as well.

According to HUD, states with the highest rates of homelessness per 10,000 people were New York (46), Hawaii (45), California (38), Oregon (38), and Washington (29), each significantly higher than the national average of 17 persons per 10,000. The District of Columbia had a homelessness rate of 94 people per 10,000.

And like the JCHS report, HUD also found disturbing data on the disproportionate number of Black people who are now homeless.

For example, although the numbers of homeless veterans and homeless families with children declined over the past year, Blacks were 40% of all people experiencing homelessness in 2019, and 52% of people experiencing homelessness as members of families with children.

These racial disparities are even more alarming when overall, Blacks comprise 13% of the nation’s population.

When four of every 10 homeless people are Black, 225,735 consumers are impacted. Further, and again according to HUD, 56,381 Blacks (27%) are living on the nation’s streets, instead of in homeless shelters.

The bottom line on these research reports is that Black America’s finances are fragile. With nagging disparities in income, family wealth, unemployment and more – the millions of people working multiple jobs, and/or living paycheck-to-paycheck, are often just one paycheck away from financial disaster.

Add predatory lending on high-cost loans like payday or overdraft fees, or the weight of medical debt or student loans, when financial calamity arrives, it strikes these consumers harder and longer than others who have financial cushions.

And lest we forget, housing discrimination in home sales, rentals, insurance and more continue to disproportionately affect Black America despite the Fair Housing Act, and other federal laws intended to remove discrimination from the marketplace.

The real question in 2020 is, ‘What will communities and the nation do about it?’

For Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, an assistant professor of African American studies at Princeton University and author of the new book, “Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership,” federal enforcement of its own laws addressing discrimination and acknowledging the inherent tug-of-war wrought from the tension of public service against the real estate industry’s goal of profit, there’s little wonder why so many public-private partnerships fail to serve both interests.

In a recent Chicago Tribune interview, Professor Taylor explained her view.

“You don’t need a total transformation of society to create equitable housing for people,” said Taylor. “We have come to believe that equitable housing is just some weird thing that can’t happen here, and the reality is that we have the resources to create the kinds of housing outcomes that we say we desire.”

“The way to get that has everything to do with connecting the energy on the ground to a different vision for our society — one that has housing justice, equity and housing security at the heart of it,’ Taylor continued. “The resources and the money are there, but there’s a lack of political will from the unfortunate millionaire class that dominates our politics… I think, given the persistence of the housing crisis in this country, we have to begin to think in different ways about producing housing that is equitable and actually affordable in the real-life, lived experiences of the people who need it.”

Amen, Professor Taylor.

Charlene Crowell is the Center for Responsible Lending’s communications deputy director. She can be reached at [email protected].