Throughout Black History Month and African American studies classes, students and people around the world hear about the great story of civil rights activist Rosa Parks and how she refused to give up her seat to a White passenger on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. However, very few people know of civil rights martyr, Samuel Mason Bacon.

In March of 1948, Bacon, a 61-year-old African American man, decided to take a bus trip from Akron, Ohio to Natchez, Mississippi, his home town, to visit his family.

During his trip to Natchez, he had to switch buses. After finding a seat on the new bus, Bacon was ordered by the bus driver to get up and allow a White man to sit there, despite the fact that there were seats available in the section of the bus designated for Whites.

Bacon responded to the bus drivers request with a firm, “no.” At the next bus stop in Fayette, Mississippi, which is just one town from Natchez, Mississippi, the bus driver had Bacon arrested. Following the arrest, Bacon was placed into custody. As Bacon sat in the jail cell, he was visited by Town Marshal Stanton D. Coleman, who shot Bacon twice resulting in his death.

During the time of the incident, the sheriffs alleged they arrested Bacon for disorderly conduct and intoxication. They also claim that they had accidently put him in a jail cell where they had left an axe. The sheriffs claim they had to shoot Bacon twice in self-defense because he had an axe and was going to hurt one of the sheriffs with said axe.

So why is Bacon being honored by his home town 70 years later?

The L.A. Sentinel spoke with Kaylie Simon, the Project Director of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project (CRRJ) at Northeastern School of Law. As part of their job, the CRRJ investigates cases, looks up old records, and collects all of the findings to ensure that the information is not lost or forgotten.

“Part of that is to make sure that the history isn’t lost and that history is preserved for us to understand the time and also for future generations to learn from this period,” said Simon.

“The second part of the project, is to ask the relatives of the people who were killed, ‘what would you like to see happen today?’ ‘What would justice look like to you today?’ Sometimes no legal remedies are available, but our philosophy is the family still deserves acknowledgement, recognition, and repair for what happened to their family and their communities.”

After CRRJ Director Margaret Burnham investigated the Bacon case, she reached out to the family to conduct interviews and organize an event to commemorate his legacy.

On March 17, family members and local residents gathered at the Natchez Museum of African American History and Culture in Natchez, Mississippi. During the event, Burnham, Fayette Mayor Londell Eanochs, Natchez Mayor Darryl Grunnell and Bacon’s family gave their remarks.

“Nobody wakes up thinking, today I am going to standup for myself and my people and die for my people and die for my rights,” said Burnham in her speech.

“On that day when Samuel Mason Bacon decided to not give up his seat, he was making a statement that he was going to stand up for his rights and his people’s rights.”

Mayor Eanochs, had this to say regarding the death of Bacon:

“I, Londell Eanochs, by virtue of the power vested in me as Mayor of the city of Fayette, do hereby recognize the injustice done by then Fayette Police Department and to acknowledge and give a formal apology on behalf of the city of Fayette.”

Additionally, during the event, Fayette Police Captain Dia Grover presented an official resolution from the city of Fayette recognizing and apologizing for the killing of Bacon. The event followed with a reception and the unveiling of a new gravestone for Bacon at St. Mark Missionary Baptist Church.

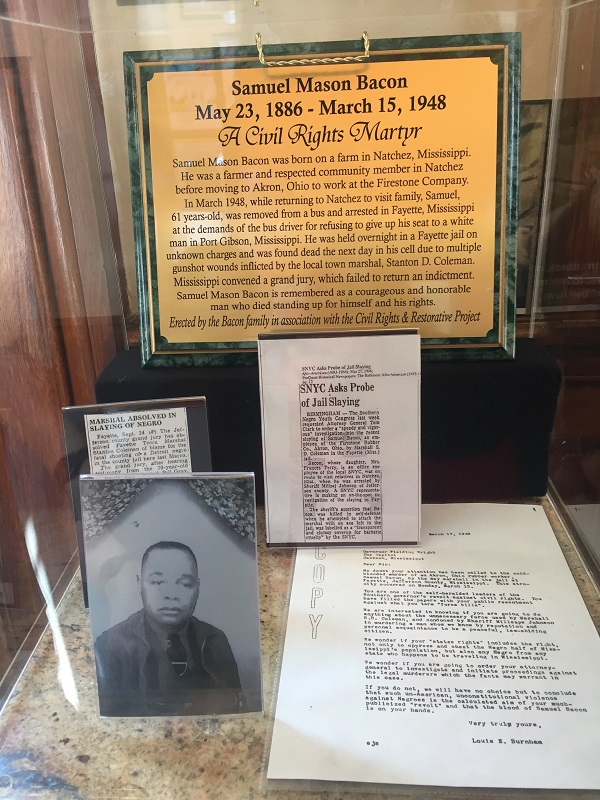

As a result of the CRRJ and Bacon’s family coming together, there is now a permanent exhibit in the museum so that future generations can learn about his story.

“This was an awe-inspiring affair,” said Bacon’s 85-year-old grandson, James Darrell Broach who was 15-years-old at the time of his grandfather’s passing.

“What I learned most about this is justice. I realized during the ceremony and leading up to the ceremony that most people including myself, we look at justice in terms of punishment for the person who committed the offense. During this preparation and this participation in this affair, I realized that I was looking in the face of justice. I was witnessing the reward of justice and that was very satisfying.”

Broach goes on to say that “forgiveness must be present otherwise there is no justice.”