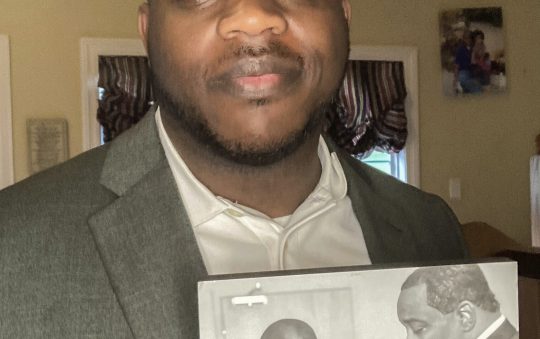

Though the name "Bob Jones" is a common name, there was nothing common about Robert Gooden Jones, a Motown legend, a publicist, an author and also well known as vice president of Michael Jackson's MJJ Productions. He was born in 1936 in Fort Worth, Texas, to Ruby Fay Jones and Ocie Jones, a music promoter who introduced his young son to the world of music. His life story was as colorful as it was interesting, based on his work, his career and his accomplishments. Around 1951, during his teenage years, he and his family moved to Los Angeles.

In addition to studying communications at the University of Southern California, Jones was an avid reader of happening in the showbiz world. While in high school, he began writing a social column for the California Eagle, one of the first Black newspapers in California. He then became the entertainment editor of the Herald Dispatch–a local newspaper in Los Angeles–where he covered the Black community and wrote a weekly column, "Bob Jones in Hollywood," about Black issues in Hollywood which was syndicated in about 80 Black newspapers around the country. And since the Dispatch also published the "Muhammad Speaks" column, written by Malcolm X, Muslims in the Nation of Islam sold the paper around the country, which gave Jones' column additional national exposure. He reportedly said, "I was telling everybody's business but my own."

In 1968, after ten years at the newspaper, he was interviewed by a public relations (PR) firm, Rogers & Cowan, and what started off as a two-week PR stint with the Supremes, blossomed into a full-fledged career as a publicist. (The interview grew out of his friendship with entertainer Bobby Darin). Two years later, Jones was doing PR work for Berry Gordy at Motown. He was in a very unique position, for there were not many Black publicists and those in the business were usually working with one client at a time. At Motown, Jones had an array of high profile individuals and groups with whom he worked simultaneously.

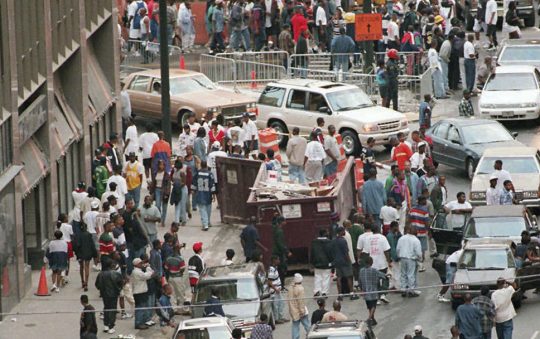

Though Jones' was not as well known as the people for whom he labored, the results of his work at Motown was celebrated worldwide. He controlled much of what the public knew about some of the most influential artists of Motown during the seventies and most of the eighties. He represented a roster of superstar entertainers including Michael Jackson and the Jackson Five, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Lionel Richie and the Commodores, Rick James and Motown's founder, Berry Gordy. In so doing, Jones practically shaped the popular culture in the entertainment industry. Even those whom he did not represent directly were familiar with his work.

Whenever Motown entertainers were introduced to the public, it was Jones who made it happen. Jones held the mirror that reflected Motown to the public in an even-handed manner. If the mainstream (White) media did a story on a Motown star, Jones would make sure that the Black media (Jet, Ebony, Essence, etc.) had equal access; he was an equal opportunity publicist for the famed label. In other words, Jones made certain that the Black press was treated with respect; he dealt fairly with them. His work ethic came from remembering the sacrifices his mother made as "she did a lot of White folks kitchens to help me" so that his life would be better than hers. He was also hard on Black entertainers if they got out-of-line or disrespectful.

In 1987, after 17 years, he left Motown to be the vice president of MJJ Productions. His association with Jackson's company predated his relationship with the superstar. He acknowledged that working for Jackson allowed him to operate in a whole different world, such as visit with presidents and royalty to do things many Blacks have not been able to do. However, Jones also said, "My world is still black." He dubbed Jackson "the King of Pop" and stayed with MJJ Productions until 2004 guiding him through his "peaks and valleys," and his minefields of unprecedented idiosyncrasies and eccentric behavior.

Understanding the importance and the impact of tradition, he wanted to be certain that he was able to pass the benefit of his knowledge to the next generation of Blacks in the entertainment industry. Jones said, "I would have accomplished nothing in this life if I was not able to bring another one along. I hope that those I've brought along will bring another one and another one." His most enduring achievement was that of a mentor. And though he was professionally labeled a publicist, Jones also nurtured and helped launch the careers of musicians, photographers, actors, journalists, managers, agents, executives and of course publicists.

According to the mainstream media, his relationship with MJJ Productions went sour in 2004 and Jackson terminated Jones, via a caustic letter. The parting was acrimonious and it left devastating wounds on both parties. Jones then decided to write a biography about his former employer; it was co-written with Stacy Brown. The book was very unflattering, and to some, the ranting of a disgruntled, ex-employee. Titled, "The Man Behind the Mask," Jones' hoped that his three decades plus relationship with Jackson would give the book credibility and substance. It was promoted as a true insider's account because of the number of years Jones had spent with Jackson. He reported on Jackson's "unusual" behavior and reportedly "leaked" stories to make Jackson seem mysterious, such as his sleeping in a pressurized horizontal chamber and his seemingly unusual relationship with Bubbles, the chimpanzee.

When Jones was a young writer, he stated about his column, "I was telling everybody's business but my own." In his tell-all book, not only was he telling about Jackson's business, he was also telling everybody about his own business. Prior to the book's publication, Jones had always been the man behind the scenes, the one who promoted others and crafted their images for public consumption. The book introduced Jones to the public for consumption.

Some, including Jones' co-author, who knew both Jackson and Jones, believed that throughout the book, he portrayed a sense of loyalty to the superstar by omitting a treasure of potentially shocking details. Even when Jones testified at Jackson's trial on child-molestation charges in 2005, Brown said that he backed away from testimony–telling all he knew–that might have helped the prosecution. Jackson was acquitted of all charges.

Jones died in on September 20, 2008, a mere seven weeks before Barack Obama won the presidency, an event he badly wanted to see–the notion of a Black man in the White House seemed sheer fantasy to Jones.