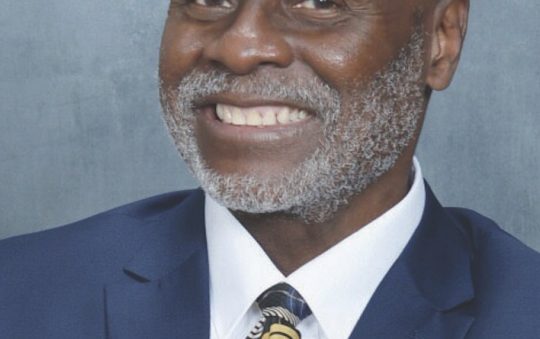

Dr. Cecil Murray, Cecil Murray Center for Community Engagement, Center for Religion and Civic Culture, USC

After two years of being an unemployed apprentice in the Iron Workers Union, 24-four-year-old Leray Williams landed a job on a large project. He got to work at 4:30 a.m. every morning, organized his tools, and always finished his assignments in time to offer a helping hand to others on the site. As a second- generation ironworker, he knew how difficult it is for Black construction workers to secure employment and he wasn’t going to let anything cause him to miss this latest job opportunity. Nothing, that is, until a noose was hung at the jobsite. Williams endured seven months of hearing racist slurs and “jokes” from those with whom he worked and had to trust with his life.

“Betty,” a Black woman who worked as an administrative assistant to top entertainment executives, filed a formal complaint after she learned that a lesser-experienced white woman she had trained was classified higher and paid more, for doing significantly less work. After bringing it to management, there was no follow-up. “Betty” was terminated after reporting employment discrimination. Being terminated for pursuing enforcement of your workplace rights is patently in violation of Title VII.

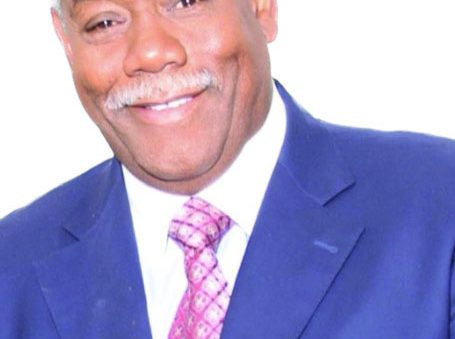

Rev. Kelvin Sauls, senior pastor Holman United Methodist Church and member of the LA Black Worker Center Coordinating Committee

Andre, an African American father of twin boys, searched nearly 2.5 years for work. Armed with extensive pre-apprenticeship certificates he would wake up at 4:00 am every morning to search for work at multiple construction sites across Los Angeles. He rarely saw people who looked like him on the job sites and was met with blank stares. Foreman never took his resume and some even called the police on him as he waited outside their worksites, hoping for opportunity.

Employment discrimination like that experienced by these three workers remains an unfortunate yet prevalent reality for too many workers in our city, especially Black workers.

50% of Los Angeles’s Black community is unemployed or underemployed (making less than $12.00 an hour). In growth sectors such as the public construction industry, Black workers represent 10 percent of trained apprentices but make up less than 3 percent of the workforce. In the private construction industry specifically, Black workers make up only three percent of the workforce. When we have done the hard work of getting black people into the pipeline for jobs they still aren’t being hired. And when Black workers do make it onto the job they experience violations of wage theft at twice the rate of white workers. The laws are on the books, but enforcement of them is sorely lacking.

Tuesday, the Los Angeles City Council took a monumental step toward improving workplace conditions for LA workers by directing the city attorney to draft a minimum wage ordinance with comprehensive wage theft enforcement. This means the city minimum wage would rise to $15 by 2020. In the 14-1 vote, the Council also advanced comprehensive wage enforcement, critical companion legislation that establishes an Office of Labor Standards and Enforcement (OLSE) at the city level to protect workers against wage theft and unlawful employer practices that prevent them from collecting their wages. We have been part of an effort, spearheaded by The LA Black Worker Center, to ensure the ugly and pervasive practice of employment discrimination is a key part of comprehensive wage enforcement.

However, we watched in disbelief, as the anti-discrimination enforcement failed to get the votes needed to be included in framework of the policy, which will be approved by council next month. Instead, the provisions were referred back to City’s Economic Development Committee for review.

To LA City Councilman Curren Price, who drafted the anti-discrimination amendment and supporters, Council members Gil Cedillo; Herb Wesson; Paul Koretz; Nury Martinez; Mike Bonin; and Jose Huizar, we say thank you for your courage to stand for anti-discrimination and protect workers from unscrupulous employers who would deny work opportunity based on the skin color, gender, or sexual identity.

To Los Angeles, we ask: why do workers have to wait for anti-discrimination enforcement at the city-level?

When Black people are not hired, are underpaid, have their wages stolen, and are mistreated on the job the repercussions go far beyond that individual who has been discriminated against. Our families are destabilized and the resulting poverty is at the root of mass incarceration, homelessness, health disparities and the educational divide.

By creating and fully funding an OLSE, Los Angeles would join at least 10 other cities across the country that have created city level offices to protect workers. These offices take on a range of responsibilities that go far beyond referrals to address the very challenges faced by so many black workers in our city. A Los Angeles OLSE could play multiple roles in the enforcement of anti-discrimination protections for workers:

- Regularly collect data on workforce demographics, conduct audit studies of problematic industries, and impose penalties on employers that break the law

2) Enforce anti-discrimination protections for current employees and applicants through co-enforcement partnerships with community-based worker organizations and organized labor

3) Investigate and adjudicate claims of discrimination over which the City Attorney has jurisdiction, while assisting state and federal agencies in outreach, investigation, and mediation of claims of discrimination that violate state and federal statutes

4) Promote community and employer education in partnership with community-based worker organizations and organized labor.

The city will have strong partners in community based organizations like the LA Black Worker Center who are already doing some of this work, but need to muscle and resources a strong OLSE will provide.

Current proposals floating in City Hall include a call for $400,000 to fund an enforcement effort here in Los Angeles. San Francisco, a city with a third of our workforce, spends $1.8 million to run its Labor Standards office that employs 5.5 investigators, and contracts with community organizations to do targeted outreach and education. The paltry proposal for $400,000 to fund enforcement in our city is totally insufficient. Considering our size and the magnitude of our problem, a LA OLSE needs 15-25 investigators and a budget of $5.5 million to run an effective office. These costs would be offset through the collection of fines and penalties of violators and through partnerships with the state and federal government who have reimbursed other local jurisdictions for doing such work. This will come on top of recouped tax dollars from justly employed workers.

Some will say this is too expensive but few dispute the connection between joblessness and rising crime rates. Our city spends $1.189 Billion on policing, and the current climate reveals how this cost and the criminalization of our community that too often comes from it is already too much to bear. The employers who deny Black people access and exploit and harass them on the job are criminals and we need to invest in policing them.

Some will say this work is duplicative of work done at the state and federal level, but a strong intergovernmental partnership is needed to address this issue. The magnitude of the Black jobs crisis requires it.

We have a unique opportunity to demonstrate that Black Lives Matter in the city of Los Angeles. We urge members of the Los Angeles City Council to establish and fund an effective OLSE that aggressively enforcement employment discrimination.

Now, the fate of anti-discrimination enforcement lies in the hands of the Economic Development Committee. We urge the committee to put this issue at the top of its agenda and ensure these protections are part of LA’s landmark minimum wage/comprehensive wage enforcement ordinance. Workers in our community cannot wait. As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said: “Wait, means never.”