The morality of remembrance is deeply and indelibly rooted in the culture and consciousness of African people. Indeed, it is expressed repeatedly in our ancient sacred texts and in the ways we recount and celebrate the exemplary lives and deeds of our ancestors, seeing them as models of excellence and achievement we are obligated to emulate. And it is similar in our remembering, celebrating and striving to emulate the living legends and doers of awesome and everyday good among us.

The Husia teaches us to pour libation for our ancestors at home and away and to constantly raise and praise their names for the good they have done, causing them to continue to live and have eternal meaning among us. For it is written “to do that which is of value is for eternity. Persons called forth by their good works do not die, for their names are raised and remembered because of it”. And the Husia also teaches us, a people engaged in righteous and relentless struggle for good in the world, to remember and learn the lessons of the past. For “If people fight on the battlefield forgetful of the past, success will elude them, for they are unaware and neglectful of what they should know”.

Moreover, the freedom fighter and human rights activist, Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, taught us the morality of remembrance, saying “There are two things we should care about: never to forget where we came from and always praise the bridges that carried us over”. Here she teaches us first to care, then to remember and afterwards to praise. For if we care, we will remember, and if we remember rightfully, we are compelled to praise the doers of good and the givers of great and small gifts that enrich and expand our lives.

This year’s Black History Month theme, given by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), is “Hallowed Grounds: African American Sites of Memory”. It invites us, the explanatory literature says, to remember the sacred sites where decisive and defining struggles, events and victories occurred. As Dr. Carter G. Woodson, the founder of both the celebration and organization, urged us, we are to celebrate and commemorate in varied, instructive and uplifting ways. But we must do this in ways that ensure we see and engage these sites as sacred or hallowed grounds, and not reduce ourselves to tourists and them to tourist stops. That is to say, places to see, but not to hold hallowed; sites for selfies, but not for rituals of rightful remembrance and praise.

This means first that we be clear about the difference between tourist sites for others and hallowed ground sites for us. For hallowed means declared and made sacred or holy, and to do this we must engage it as such, i.e., set aside and secured against violation, devaluation and degradation. In our ancient sacred texts, we are told to take off our sandals or shoes to stand on sacred ground; to come with clean hearts and minds, void of all evil and petty thoughts and emotions; and to approach it with awe and engage in practices of respect, remembrance, thankfulness, thoughtfulness and praise.

Thus, we do not approach these sites as simple listings or places to go and things to see, detached from the life-and-death struggles, the great hardships, sacrifice and suffering, the awesome casualties and costs and the hard-won triumphs against all odds that made these sites sacred. Instead, we engage rightfully in rituals of remembrance: pouring libation; raising and praising names and deeds; offering prayers and singing songs; giving readings and recitations; reenacting and recounting sacred, moral and life-honoring narratives; playing music and doing meditation. In a word, we are to act and perform in ways that uplift and advance good in the world and also honor our cherished legacy by striving to embody it and express it in the way we live, love, work and struggle.

Moreover, we must extend our concept of “hallowed ground” beyond sacred physical sites and see “ground” as all “sites of fundamental significance”. Thus, our history itself is hallowed ground, as is our culture and above all, our person and our people. As I’ve said so often, there is no people more sacred than our own, no history more holy or worthy of being taught and told, and no culture more ancient, rich or capable of revealing and representing the best of what it means to be human in world-encompassing ways.

It is in this spirit that August Wilson, among the greatest of playwrights in the world and embracing of Kawaida philosophy, speaks of the hallowed ground of our personhood, peoplehood, history and culture. He says, in a speech titled “The Ground On Which I Stand”, “I stand myself and my art squarely on the self-defining ground of the slave quarters, and find the ground to be hallowed and made fertile by the blood and bones of the men and women who can be described as warriors on the cultural battlefield that affirmed their self-worth”. Moreover, he says, “As there is no idea that cannot be contained in Black life, these men and women found themselves to be sufficient and secure in their art and their instructions” (emphasis mine). And I read “secure in their instructions” as secure in the lessons of their lives, the teachings of life, love, work and struggle from the culture and consciousness of their own, our own people.

We must, then, hold sacred the whole of who we are and be secure in ourselves about the sacredness of our personhood and peoplehood. And we must recognize, remember and be constantly attentive to what Anna Julia Cooper called Black women’s, and by extension Black men’s, continued and life-and-death “fight to keep hallowed their own persons”. It is as we know, a fight to keep ourselves as Black women, men and children safe and secure from the official and unofficial violence of society and the state. And this means, not only against police violence, but also against psychological violence of a racist and disabling education, the socio-economic violence of structural poverty, unemployment, inadequate and inaccessible health care, and all other systemic and sustained violence against our people.

And here, we are inevitably led back to the issue of struggle, righteous and relentless struggle which provides and produces the hallowed ground on which we must ultimately stand. It is a struggle that defines and provides the foundation and forward motion of our history, and gives substance to our celebrations and practices of remembrance. And this is one of the main reasons we cannot allow government officials or their associates to change the name of “Black History Month” to “Black Heritage Month”. For it is a violation of the work and memory of Dr. Woodson who established it; a violation of the self-determination of a people who chose its own name for its own celebration; and it is a violation of the spirit and intent of the holiday directed toward making history a living practice of emulation, advancement and struggle.

Heritage is what is handed down and passed on; history is the struggle, process and practice that brings heritage into being and links our past, present and future in a seamless motion. For again, the legacy and lessons of history teach us that this is our duty: to know our past and honor it; to engage our present and improve it; and to imagine a whole new future and forge it in the most ethical, effective and expansive ways.

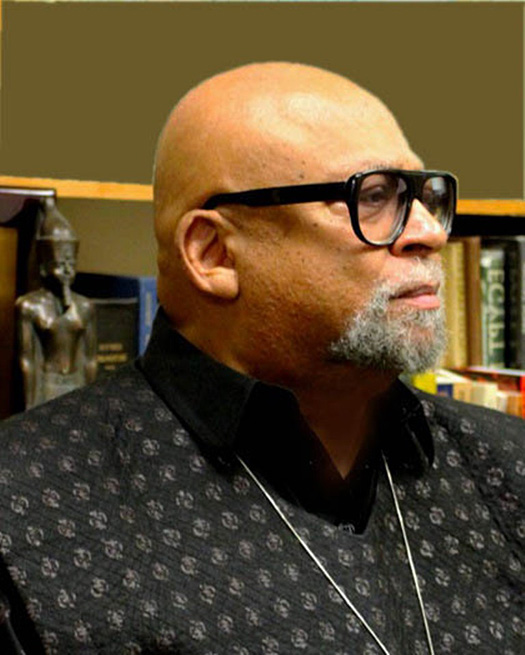

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.