Proclaiming clean water as a human right, Groundswell for Water and Housing Justice convened leaders of L.A.’s Black and Brown communities to address this pressing issue that disproportionately affects people of color.

The gathering held March 27 in View Park featured Rick Callender, president of the NAACP California – Hawaii State Conference and CEO of the Santa Clara Valley Water District in the Bay area. More than 100 attendees listened as he outlined the reasons that both Groundswell and the NAACP have launched safe water campaigns.

“I want to thank Groundswell for encouraging people to get involved in these water justice and environmental justice issues. We have to hold everyone accountable – including our friends,” said Callender.

“Clean water is a basic human right and should be accessible to all, regardless of socio-economic status or racial background. Every level of government bears the responsibility for its citizens to have access to safe drinking water,” he stressed to the audience, which included Compton Mayor Emma Sharif, L.A. Councilmember Heather Hutt, MWD Board President Adán Ortega Jr., and L.A. County Fed President Yvonne Wheeler.

Representing the faith community were the Rev. K.W. Tulloss, the Rev. Dr. D. Najuma Smith-Pollard, the Rev. Lawrence Blake, and the Rev. Dr. Larry E. Campbell along with scores of pastors from the Baptist ministers Conference, Los Angeles Metropolitan Churches, and AME Ministerial alliance.

Explaining Groundswell’s role in the campaign for safe and affordable water, spokesperson Ed Sanders said the coalition was formed and inspired to action by a report from the California state auditor noting that nearly one million residents lacked access to clean water.

“We are focused on finding equitable solutions for the nearly one in 40 Californians who live with water insecurity. Water is life. We need it to cook, to bathe, to live,” said Sanders. “And when you look to see where water systems are failing, it’s primarily in communities of color.”

While people in L.A. may not view water insecurity as real urgent, residents of rural area and inland cities such as Palmdale, Lancaster, and Riverside rate the issue as much more important, according to Sanders.

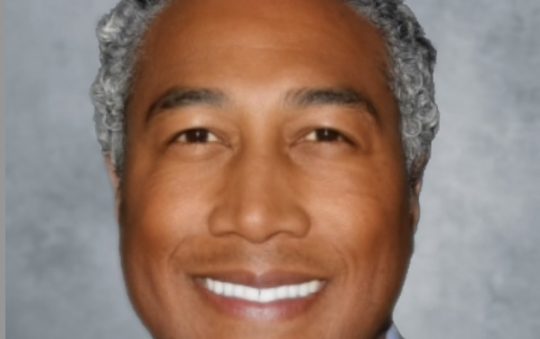

Rick Callender; Darrell Goode, NAACP Southwest Area Director; and Mike Asfall, Beverly Hill-Hollywood NAACP. (Ian Foxx)

“With climate change over the last few years, we’ve gone from drought-like conditions to atmospheric rivers and tropical storms. We, as a community, have to evaluate how the state is capturing, storing, and transporting water to the population,” he insisted.

Encouraging the public to join Groundswell’s grassroot campaign, both Sanders and Callender urged people to support legislative initiatives to invest in water infrastructure, enforce regulations on pollutants and contaminants in water sources, and involve local communities in decision-making processes.

Another priority of Groundswell is to end the legacy of discrimination regarding access to clean water. In printed literature, the organization contends that historical segregated housing “forced people of color to form communities outside of city limits,” which led to “a deliberate lack of investment to meet their needs.”

The recent water crises in Flint, Michigan and Jackson, Mississippi provide telling examples of government policies negatively impacting majority-Black cities. Also, Black neighborhoods in Houston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia face ongoing water issues. Groundswell for Water Justice aims to prevent similar calamities in California.

“The question of water supply management for the state of California is an issue we need to deal with to develop common-sense solutions to the climate crisis,” said Sanders.

“Groundswell wants to ensure that the water management strategy prioritizes delivering clean water to all communities throughout the state.”