When Nana Haji Malcolm X taught and stressed the foundational importance of the critical study of history, he was responding not only to the ongoing need for historical knowledge in all times and places, but also to the context of his times and the liberational role of history in the unfolding Black Freedom Movement.

Indeed, for him critical consciousness must first be rooted in and reflective of historical knowledge, consciousness of history, especially given the conditions of forced and cultivated historical amnesia and the falsification of history by a brutal racist oppressor. In my forthcoming major work on Haji Malcolm titled “The Liberation Ethics of Haji Malcolm X: Critical Consciousness, Moral Grounding and Transformative Struggle,” I speak extensively to his centering of history as a foundational, even indispensable, knowledge in life and struggle. Below are some excerpted concepts and considerations from this work.

It is for Haji Malcolm, within the framework of his liberation ethics, not only an ethical requirement to seek and acquire knowledge, but also, an equal ethical obligation to use historical and other forms of knowledge as a practice of freedom, the freeing of the mind, and putting it in the service of the liberation struggle. And it is a reaffirmation of the Kawaida contention that knowledge is not for knowledge’s sake, but for human sake, that is to say, in the interest of African and human good and the well-being of the world.

It is in the context of this understanding of history that Nana Malcolm puts forth his classic statement about the foundational character and fruitfulness of knowing history. He states that “of all our studies, history is best qualified to reward our research.” Reaffirming this position to emphasize its universal applicability, he also says “of all the things that the Black man (woman), or any man (woman) for that matter can study, history is best qualified to reward all research.”

And continuing this essential emphasis, he asserts that “you must have knowledge of history no matter what you are going to do; anything that you undertake, you have to have a knowledge of history in order to be successful.” It is, he would no doubt argue, no accident that no matter what subject we teach or learn in or out of the academy, we begin with the history of that subject.

Haji Malcolm begins his essential lectures in African American history by noting that his lecture series is “designed to give us a better knowledge of the past, in order that we may understand the present and be better prepared for the future.” He goes on to assert that “I don’t think any of you will deny the fact that it is impossible to understand the present or prepare for the future unless we have some knowledge of the past.” Here Haji Malcolm affirms his appreciation of history as an indispensable aid to understanding the current conditions of our lives, the factors and forces that created and sustain these conditions, and the possibilities of change and building a new future in struggle based on this understanding.

Therefore, Haji Malcolm finds common ground with W. E. B. Du Bois who informs us that “We can only understand the present by continually referring to and studying the past. When any one of the intricate phenomena of our daily life puzzles us; when there arise religious problems, political problems, race problems, we must always remember that while their solution lies in the present, their cause and their explanation lie in the past.” Thus, it is with the problem of struggle and the crafting of a strategy of struggle in light of history, current conditions and projected future possibilities.

Again, Nana Malcolm is concerned with the liberational use and function of history as with knowledge as a whole. Learning history, like learning about self, society, and the world in significant and meaningful ways, becomes a liberating practice in the preparation and pursuit of struggle. Thus, in a typical language of liberation struggle, he states that to know the history of ourselves and the history of our oppression and oppressor enhances our capacity and promise of victory.

He asserts that “When you and I wake up . . . and learn our history, learn the history of our kind and the history of the white kind, then the white man will be at a disadvantage, and we’ll be at an advantage.” For then we will know the origins and causes of our oppression and the ways in which the oppressor falsifies Black and human history in order to paint a diminished, degraded and inferiorized portrait of African people in order to deny our humanity and human achievement and thus undermine our sense of worthiness and possibility and our will to act and resist. Knowing this will in turn strengthen our will and expand our knowledge to resist.

Indeed, Haji Malcolm maintains that the oppressor is aware of the importance of history and that is why he engaged in a calculated plan to create historical amnesia in his victims, to erase their memories, falsify their history, and create conditions of social and cultural death for them. Thus, he would point to the lessons of history as well as current developments to explain the production of policies in which White supremacists are banning our books, falsifying, and denying the horrors of the Holocaust of enslavement, declaring our history no longer relevant or fruitful, while making infantile and hysterical claims of racial discomfort and racial exemption from the teaching and telling of truth.

Here Nana Malcolm is stressing the need for putting things in context, especially historical context, so that we can understand the historical origins of our condition and the possibilities of our transforming them. He contends that a right reading of history will lead us to both necessary insight and action, to insight into the origin and nature of our oppression and the possibilities of overcoming it and to radical action to end it and build a new life and society based on freedom, justice and righteous relations of brotherhood and sisterhood.

Therefore, he states that “If we don’t go into the past and find out how we got this way, we will think that we were always this way,” i.e., oppressed, unfree, deprived and disadvantaged. His point here and elsewhere is to understand our oppression as a historically evolved and imposed condition that interrupted our freedom and achievements, and that we are morally obligated to resist our oppression and reclaim our freedom.

Minister Malcolm, then, stresses the study of history as a reparative, transformative and liberating practice and process which gives “knowledge, confidence, incentive, inspiration, energy” which is vital to the project and practice of liberation. And again, Haji Malcolm is concerned that the oppressed, in this case Africans, not mystify their oppression and misconceive it as always existing and permanent.

On the contrary, he wants them to see it as an imposed and changeable condition and begin to resist and end it. And as always, he calls on the oppressed to wake up, clean up and stand up to confront and change it and build a new and righteous world, drawing from and building on the high-level achievements and models of the past as well as lessons learned from the lives we live, the work we do and the struggles we wage, internally and externally, for the good world we want and deserve. The need, then, is to carefully and critically study history to discover origins, meanings, causes of development and lessons for moving forward in the most righteous and effective ways.

Haji Malcolm saw history not simply as knowledge of the past, then, but also as an applicable and effective knowledge in grounding and guiding one’s thinking, learning, life and liberational struggle, and in understanding and practicing one’s faith as both internal and external righteous striving for the good. Also, he saw an effective knowledge of history as central to coming into critical consciousness about ourselves, our oppression and oppressor, our options and possibilities in struggle, and all things necessary and related.

For in the final analysis, Haji Malcolm saw at the center of all our strivings and struggles the reclaiming of our freedom, and building, with others similarly committed, a new world of inclusive and expansive good and initiating a new history and future of humankind.

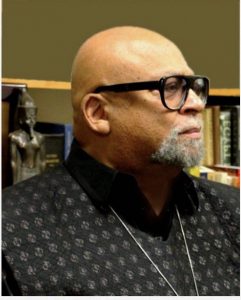

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.